Your cart is currently empty!

Category: COVID-19

-

Quarantined Visions: Part Two (Italy)

A Close Look at Quarantine Art from COVID’s Past Mecca“Quarantined Visions” continues with a selection of work from artists locked down in Italy. The first installment of this series exposed artwork from China, the country that suffered through the original outbreak and quarantine brought on by COVID-19. Part Duo takes us to Italy, the first European country to impose nationwide restrictions, and an extroverted society uniquely unsuited for a viral contagion.

This author’s girlfriend has Italian family; upon hearing that the virus was spreading there, she warned of dire consequences. The culture of towns and cities in Italy “is intensely social…with everyone saying, Andiamo al Bar daily to chat, drink, hug and gossip”. This familial physicality, along with an aging and vulnerable population, created the perfect COVID storm and necessitated one of the most rigorously enforced quarantines in the world. It was, as one artist put it, an “imprisonment.” Since February 22, when lockdowns began, there have been at least 243,500 confirmed cases of coronavirus with 34,997 people dead—although a recent government study suggests that many more Italians may have succumbed than the official numbers let on.

But now, as of this writing, Italy has officially crushed its curve.

During it all, there were positive gestures that reflected the culture’s natural exuberance and tenacity. The challenge of total lockdown was met with music, performance and prosecco toasts across streets with glasses attached to poles. It was also accompanied by artists continuing to make new pieces in direct connection thematically to the “quarantina” (a word, salient to this context, that comes from “quarantena” in the old Venetian language, meaning “forty days” —the length of isolation practiced to prevent the spread of the bubonic plague). Often, the artists featured in this article found themselves diverting or improvising from their normal practices, as access to studios were prohibited for many. The following is a small selection of work from all over a country just emerging from a national nightmare.

Antonello Tagliafierro, Let’s Hope to Be Free Soon,1975-2020, photograph, acrylic Antonello Tagliafierro’s pre-COVID practice was mainly abstract, but lockdown led him to alter an old photograph in an image that, while titled Let’s Hope to Be Free Soon, very much speaks for itself. Tagliafierro (b. 1952, lives and works on Caserta) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, and started producing art around the mid-’70s, with paintings inspired by the images of the mass media, mixed with more public political interventions.

Pietro Campagnoli, 2020, “Stone 3”, 170x55x65 cm, resin The idea of the enclosed body yearning to be free is also a theme in Pietro Campagnoli’s monumental sculptures based on body casts. Campagnoli (b. 1994, Turin), grew up with the challenge of Asperger’s syndrome, and his difficulty relating in high school was perhaps what drew him into art. He creates his sculptures by soaking wet blankets in gypsum, placing them on living bodies and waiting for them to solidify. The works are faceless, empty shells, “like a chrysalis.”

Emilia Castioni, “Uomo a Letto”, 2020, 23cmx23cm, photograph The new work of photographer Emilia Castioni is striking in its eccentricity and poignancy. Born 1979 in Sarnico, she grew up and works in a commune not far from the hard-hit Bergamo region in Northern Italy – an area that saw 5000 deaths in one month. In the lockdown period she “reflected on the feeling of suspension of time”; these images were meant in some ways to express the whiplash she felt after being “incarcerated” after living a hectic life.

Carla Viparelli (Naples, b. 1959), like many of the Italian artists represented here, is a polymath, practicing in many different formats such as video, painting, installation and drawing. Her short piece, “Stop the River”, plays with our expectations of time, movement and teeters intriguingly between anxiety and calm. See her paintings and other works at http://www.carlaviparelli.it.

Fabio Giampietro, Soundscape, 2020, acrylic on canvas The notion of “escape” is realized in another dimension with Fabio Giampietro’s wild city-ships. Giampietro quarantined in Milan, where he was born in 1974. He is best known for a unique exhibition called “Hyperplanes of Simultaneity” where he combined his dizzying cityscapes with virtual reality.

Luciano Romano, Siamo onde dello stesso mare (We are Waves of the Same Sea), 2020, mixed media Luciano Romano (b. 1958, Naples) is renowned for his photography, much of which is architecturally-based, and naturally requires an ability to roam and explore to prosper. He shifted to manipulated mixed media work during lockdown, including this moody tableaux called Siamo onde dello stesso mare (We are Waves of the Same Sea). Peruse his award-winning photography at: http://www.lucianoromano.com

Pierpaolo Lista, e non bastano ancora (and they are still not enough), 2020, photograph “QV:Italy” ends with a singular image by Pierpaolo Lista (Salerno, 1977), called “e non bastano ancora (and they are still not enough)” – a work like Tagliafierro’s piece in that it needs no explanation in our culture’s sad and poignant present context. His glass painting and photography are featured in: https://www.pierpaololista.it.

Finally, a big “grazie” goes out to a number of professional colleagues that provided invaluable help with this article: Valentina Rippa, an independent art curator based in Naples; Curator Cynthia Penna; Liz Gordon, famous in LA for the “Loft at Liz’s”, and artist Carla Viparelli for her excellent curatorial hook-ups. And, to everyone, be safe.

-

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: ‘Who Am I?’

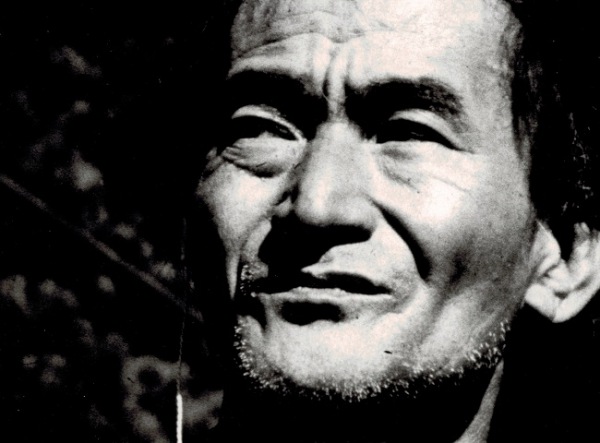

Bruce Baillie and Experimental LyricismAs part of a teaching proposal to the Autonomous University of Guadalajara in Mexico in July 1995, filmmaker Bruce Baillie makes clear what he believes to be the foundation for any kind useful communication, art, film or otherwise: “I want to present in my teaching, whatever the theme and/or external format, an essential question of Who Am I?” He believes this to be indeed essential, suggesting that without that first understanding ourselves, “we continue to live disparate, isolated lives, inventing empty and useless images which tend merely to misdirect our best efforts as a people who share a common Eden.”

Recently, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC presented Baillie’s films as part of an online shorts program in celebration of his life and artistry after his passing in April. This essential question of “Who Am I?” and in turn, “Who Are We?” guides us through Bailie’s work, and in his investigation, his films conjure feelings of compassion and humanism – what can easily be supposed as this “common Eden.” Through abstraction in composition and lyrical movement of the camera, Baillie guides us in his films with care to understand both people and landscape as part of a larger and networked society. Writing in reflection of Baillie’s 1966 short film Castro Street, Lucy Fischer suggests that Baillie “creates for the spectator an experience which transcends the nature of its literal subject.” Baillie’s films, largely functioning without explicit narrative or traditional plot, are committed to understanding our world and each other.

Still from Castro Street (1966, 10 minutes) Castro Street is a ten-minute non-narrative documentary capturing footage of a street in Richmond, part of California’s San Francisco Bay Area. From whirs, mechanics and beeps of robust and engineered architecture, to orchestral swings and bending technicolor hallucination, it becomes more clear over the course of its ten minutes that this space is, above all, occupied by and for humans. These machines do not exist on their own – they are occupied by people performing labor for free movement. Though Castro Street operates without explicit narrative, it follows a trajectory of its own – documenting the street from top to bottom (oil refinery to lumberyard; black and white to color) he underscores points of difference and dynamism on the city street. To understand the working dichotomies here is to understand how we function in cities and do so together. Castro Street demonstrates a sensibility very close to Baillie – one of deconstructing and understanding formal opposites through abstraction.

In later films, his occupation with dynamic opposition takes form around the understanding of the hero and the outsider. To Parsifal (1963) is inspired by composer Richard Wagner’s opera of the same name. Like the original work, the film exists in three acts and serves as an abstract representation of character (and hero) Parsifal’s quest for the Holy Grail. Its lyrical structure in three acts presents a voyage out to sea – it’s unclear explicitly who is represented here as Parsifal and whether or not the quest is successful, but in the context of his wider oeuvre, we can assume that the Holy Grail is nature and fertile grounds. Baillie is known as a poetic lyricist, operating in the 1960s through complex and condensed cinema. Contemporary filmmakers Michael Snow, Paul Sharits, and Hollis Frampton as ‘structuralists’ simplified filmmaking to understand the essence of its operation – but for Baillie, its content served as the essence for what he believed cinema, as a communicator, to be: a tool for understanding the self and the world.

To Parsifal is the first in a series of three films which also focus on an understanding of the world through ideas of heroism – Mass For the Dakota Sioux (1964) and Quixote (1965) comprising the next. Baillie’s Mass does not explicitly show members of the Native American Sioux tribe, but instead works as a requiem for the native people as “a celebration of what has passed away from our hysterical milieu of materialism.” Similar in form to what would later comprise Castro Street, the camera works to superimpose industry and nature; condemnation and innocence. As he followed operatic form in To Parsifal, here he follows the structure of a Catholic Mass to demonstrate the Native American’s religion-of-sorts, a commitment to nature and sustainability through time. The sombre tone of sound and music reverberates through the piece as if an accompaniment to an emblem of remembrance. Shots of the American flag behind a wired fence, juxtaposed with a heap of disused and abandoned cars piled atop one another demonstrate excess and entrapment.

Still from To Parsifal (1963, 16 minutes) The superimpositions emphasize this contrast of beauty of nature and the pitfalls of American capitalism. This is not to say he is dismissive of the evolution of technology – in fact, he seems to readily embrace the image of the train as a positive metaphor for progress. His commitment lies with understanding the dynamism between hero and misfit and their related power structures – key influences for later filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. The echoes of the question “Who Am I?” reverberate.

Quixote (1965) is perhaps the most exemplary of all of his works – it weaves together the themes and structures from his earlier films. The story of Quixote, of course, is a parodic tale of a foolish hero who wanted to be a knight and goes on a long journey to become one – here, we find in abstraction an extended reflection of heroism, war, and political action across an American landscape of beauty and advancement. Groaning sounds of industry match the abstraction of the environment – blurred shots of rural American landscape to banks, high school basketball courts and playgrounds. The sound seems to rupture over fleets of military planes, with crackled radio transmissions ominously accompanying the procession of army tanks. Quixote works as an existential examination of what it means to be American, in quixotic terms. Progress does not exist here as a throughline, in alternating from rural landscape and farmland to industrialized and militarized spaces, they exist symbiotically. Political protest – here with footage from Selma – is demonstrated as the in-between space – a space for anguish, but also for deep humanity. For Baillie, industry is not a symbol of advancement per se – there’s an argument for the great and bountiful nature of the natural environment and our power in coming together to make change. To understand each other and to improve our world, we must understand ourselves.

There’s very much a sense of mysticism around Bruce Baillie’s films – his works are distinct character portraits of landscape and offer a human view on our world. In 1997, Amy Taubin called his one-shot, three-minute film All My Life possibly “the only perfect film ever made.” The experimental lyricism of his films, and the deftly constructed cadence they offer through fusion of sound and image, create a characterization of the natural environment whereby nature feels emotive. Named the “unofficial anchorman of the West Coast underground,” Baillie founded Canyon Cinema in 1961 and worked actively to promote artists and filmmakers who used the technology of cinema for experimentation and compassion. For Baillie, filmmaking was deeply political and a tool to understand humanity. To ask “Who Am I?” is the first step to seeing and knowing the world.

-

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: Remarks on Shit Brown

Why does brown always get the short end of the stick? If it’s yellow, let it mellow. If it’s brown, flush it down. It’s not fair – earthy, practical, pragmatic brown is so much more than the leavings of a last meal. Brown is the color of the earth, your Sunday school shoes, your mother’s perfect hair.

René Magritte “Tous le jours,” (1966) Some people would kill for a brown seersucker suit, and brown is the color of good strong leather, and all the trees in the forest. So why do we denigrate brown when it goes to such lengths to be liked – ever conciliatory, patient and kind? Icky brown, mousey brown, mushroom, dun and brindle, my mother would exclaim “you’re as useless as a chocolate teapot!” And then there’s the ubiquitous brown-eyed girl with “the transistor radio, standing in the sunlight laughing.”

Egon Schiele, “Field Landscape (Kreuzberg near Krumau),” (1910). I opt for reconsideration in honor of the color that does so much for us and gets so little in return. After all, some of the best things in life are brown – mountains, sparrows, pretzels, acorns, armadillos. And the stalwart brown paper sack with the surprise that awaits inside.

-

Quarantine Q&A: Eva Chimento of Chimento Contemporary

Are you still changing exhibitions as you would if open and are the exhibitions virtual-only now? How’s that going?

I have extended all exhibitions through June 30, 2020, and will do a group exhibition in July. I have been sending previews selectively.Are you breaking any laws by opening your gallery for appointments-only, if say, a collector wanted to see the artwork before investing in buying?

I have been discouraging clients from coming for appointments and will start taking appointments Friday 13th of June. Face masks will be required and limited to 4 people at a time will be permitted in the gallery. No laws are being broken.

Eva Chimento. Are you still participating in the art fairs as they still seem to virtually exist. If so, what’s your opinion of the new virtual trend?

I have chosen not to do any art fairs this year and will be participating in Gallery Platform LA. I am still leery of the virtual trend.Do you think your space will be open this summer with limitations of how many people can enter your venue?

I will open and will have the above precautions in place.

Michael Tedja, The color guide series, On view through June 30, 2020 at Chimento Contemporary. Are openings now a thing of the past and can you foresee a new trend for announcing a new show instead of the traditional art opening?

I think it is a time will tell situation regarding openings. I think the art community will have to get creative.Is there anything surprisingly positive you have noticed so far for the art world as we know it today? Or something you feel you or we all could learn from this?

The positive: this has brought everyone closer, people checking in on one another and sharing information. Artists have gone above and beyond with encouragement for each other. I think what I am learning is that it is okay to slow down, stop and reboot if need be.Chimento Contemporary, 4480 W Adams Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90016 (323) 998-0464 -

QUARANTINE Q&A: George Davis, Executive Director, CAAM

How has exhibition scheduling been changed and how are you adapting? Are your exhibitions virtual-only now?

COVID-19 became a serious concern in California just as we were changing out our exhibitions for the spring season. One of CAAM’s new exhibitions, “Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, Nor Fowl,” opened only two weeks before we closed the museum, so few people had a chance to see it in person. Another, “Sanctuary: Recent Acquisitions to the Permanent Collection,” was set to open March 18, and two more were to have opened in April.

George O. Davis, CAAM Executive Director. Photo by HRDWRKER. For the exhibitions that are fully installed, we’ve added as much online content as possible, including slideshows of object and installation images, interviews with artists (some filmed before the closure, others recently conducted via Zoom), and video walkthroughs, all of which we share on the museum’s website and on our robust social media platforms.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl at CAAM. Photo by Elon Schoenholz. In what ways are you engaging and staying in touch with your fans and members?

Right now, we stay in touch with our supporters and let them know about our online programmatic offerings via our monthly email and frequent posting on social media.Our education staff pivoted early to move online whatever spring programs we felt would adapt well, whether than meant conversations now held on Zoom or book reviews and readers’ guides now available on our blog for CAAM’s book club. In early April we held a popular Instagram Live dance party with The Beat Junkies in lieu of our spring opening, “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop”—we called it “Can’t Stop, Really Won’t Stop.”

We’re also partnering with other institutions to enhance our online offerings. For example, a recent Zoom children’s story hour was conceived in collaboration with PEN America and featured author Natashia Deón reading books by Maya Angelou and Jacqueline Woodson. And via our status as a Smithsonian Affiliate we were a presenting partner for an online lecture about Michael Jordan by Smithsonian sports curator Damion Thomas.

We’ll continue to offer a selection of online programs—or perhaps a hybrid of in-person/online—until we can welcome groups of visitors back into the museum for public programs.

Do you think you will open in the fall? What regulations do you think you’ll implement to make museum visitation safer?

It’s difficult to tell at the moment as the authorities are constantly updating the guidelines and learning more about the virus. Like most cultural institutions, we await word from government authorities regarding how and when we can reopen. Additionally, as a state museum, our policies sometimes differ from LA County guidelines. Initially, we will make our galleries available for distanced visits.

Sanctuary: Recent Acquisitions to the Permanent Collection at CAAM. Photo by Elon Schoenholz. What’s your opinion of the new virtual trend for museums? How can museumgoers help support CAAM during this difficult time?

Actually, I think the new virtual trend for museums is great. In the past we considered digital engagement mainly as a marketing tool to get visitors to the museum. We now recognize that we’ve gained supporters from our recent pivot, some of who may never physically come into the space. I believe we will have more of a dual programming operation going forward: in-person and online.In the past five or so years we’ve developed a dedicated, passionate, diverse community of visitors; they truly are our #CAAMFam and it’s gratifying to have our institution be an important hub for African Americans as well as LA’s larger cultural community. We ask everyone to continue to engage with us online until such time as we can welcome them back in person, as well.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl at CAAM. Photo by Elon Schoenholz. Are openings now a thing of the past and can you foresee a new trend for announcing new shows instead of the traditional opening?

Clearly large openings are not a thing of the present! It’s a little sad because the energy was so great at our large openings and other public programs. Our community loves to warmly embrace friends and guests. I’m hopeful that the day will come when we can once again welcome large groups back to CAAM to celebrate our exhibitions and experience our programs. Our openings and other large gatherings, like on MLK Day, are truly special community events. Until then, we’ll experiment with ways to celebrate new exhibitions safely.

Cameron Shaw, Deputy Director and Chief Curator, interviewing Wesley Morris. Photo by HRDWRKER. Is there anything surprisingly positive you have noticed so far for the museum world as we know it today? Or something you feel you or we all could learn from this?

A silver lining is that we’ve all had time to slow down a bit and reflect on our individual impact on the planet. Like never before, we are all tied together by globalism and digital communications. We were moving at warp speed and have been forced to slow down. I hope that we will focus more on the people and stories that really matter in our society. -

Quarantine Q&A: Terrell Tilford of Band of Vices

Are you still changing exhibitions as you would if open and are the exhibitions virtual-only now? How’s that going?

Band of Vices leads first and foremost for our artists and their well-being. We recognize and respect the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and have taken every precaution to ensure that not only are we maintaining a safety net among the four partners of the gallery, but also serving our community in any ways that we can be of assistance. And while everyone is working toward the same goals and being very careful and “physically-distant” since “socially-distant” projects are something very different, just talking to our neighbors and connecting with them, supporting the local restaurants like Alta, Vees Cafe, Delicious Pizza and MizLALA including our Associated Market, we also recognize there is a need for human connection between us, especially during this time.

Band of Vices Founder & Creative Director Terrell Tilford (standing) with business partner and writer, Melvin A. Marshall. Are you breaking any laws by opening your gallery for appointments-only, if say, a collector wanted to see the artwork before investing in buying?

Our understanding is that, while there have been stay-at-home orders and that only “essential businesses” should remain open, we consider ourselves essential for our artists. Our recent exhibition which was a sold-out show, hosted maybe 10 people during its entire extended run of six weeks. During that time, each visitor was required and obliged to wearing their mask and we all maintained not just a 6-foot apart practice, but probably closer to 10 feet. If that is a law we broke, we’ll take the hit on that one.

Collector Myron Ward during Grace Lynne Haynes’ Shades of Summer exhibition, May 2020. Are you still participating in the art fairs as they still seem to virtually exist. If so, what’s your opinion of the new virtual trend?

We believe in adapting to our current climate of circumstances. And listening to our artists, our community and our clientele. While our last and next shows will still be installed, we learned and connected even more deeply by hosting our virtual talks (though they were always a part of our programming), virtual walk-throughs and just selling via social media platforms. We support whatever the virtual trend is, while also redefining for ourselves and our collector base what that may mean for them.

Opening of Shantell Martin WAVES, January 2020. Do you think your space will be open this summer with limitations of how many people can enter your venue?

We had a business meeting the other day with three partners with an artist. We each maintain a considerable distance and during that time, we also had a schedule appointment for two collectors. Everyone wore their masks and practiced a considerable distance. We have a major group exhibition with 18 artists opening on Juneteenth (June 19th), in which we are planning to be open by appointment throughout the summer. Whether there is an actual opening or if it is staggered over several days or we maintain a line outside while allowing maybe 25 people in the gallery at a time, remains to be seen. If Target and Trader Joe’s and Home Depot and other places provide practices as such, we believe we are sophisticated, yet responsible enough to do the same thing. So yes, we plan to be open and yes, we do plan to limit the amount of patrons at a time.

Shantell Martin & guest at her opening WAVES, January 2020. Are openings now a thing of the past and can you foresee a new trend for announcing a new show instead of the traditional art opening?

Openings will never be a thing of the past, they will just exist differently. There will be a new normal that we each will have to adapt to and it will become what is eventually expected. We were living in New York City when 9/11 occurred. I don’t think any of us anticipated how airline security and other measures would shape our new thinking from 20 years ago. But it did. While absolutely brutal and horrific this disease has been, we still remain optimistic and try to look beyond this moment to keep uplifting one another and what that new outlook will be, we hope to be a source of inspiration, where, through art, people continue to find their solace.

Artist Grace Lynne Haynes with Band of Vices partner, Darryl E. Wash during her exhibition, Shades of Summer, May 2020. Is there anything surprisingly positive you have noticed so far for the art world as we know it today? Or something you feel you or we all could learn from this?

We have so much yet to learn from this moment. However, what has been inspiring, again in much the same way a 9/11 was in NYC, is that people come together in times of despair. They become more compassionate, more aware, more attuned to their surroundings. The outpouring of support and therapy through the hundreds of Zoom meetings, the symposium, the parlor meetings, the studio visits, the gallery talks, the virtual tours…everyone is all-in. There is so much support and resilience and a desire to see each other remaining hopeful and productive. It truly is inspiring. Los Angeles is really stepping forward. Even during a time when you would hope the leaders of the free world would actually be leading us and assuring us, it is beautiful that everyday people have led that charge, have been the true leaders and have served as each other’s sounding boards and sources of immense, deep meaningful and sincere inspiration. -

Quarantined Visions: Part One (China)

Organized by Lawrence Gipe, “Quarantined Visions” is an online exhibition of work created during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. Beginning with images from China, this series will continue from country to country in collaboration with international curators, featuring new work by artists living in countries hit hard by the virus.

In 2019, China was maintaining its status as a major player in the contemporary art scene. The excitement was fueled by the allure and success of international art fairs, taking place mainly in Shanghai, which is the PRC’s most glittering and cosmopolitan city. As long as participating artists kept their political criticism to themselves (which was a major sticking point to some, but by no means all), a vast market of buyers appeared to be waiting – eager to join the ranks of the trendy art cognoscenti.

Then dawn broke on 2020.

The art scene in Beijing is driven by public events: installations, performances, dance, cinema…as these disciplines have gone mute during lockdown, artists have concentrated on photography and mixed media. In many ways, the work of Chinese artists has gone completely underground during the recent pandemic. This first installment of Quarantined Visions includes five artists: each worked during the lockdowns and many had to modify their usual practices given the reality of the moment.

Huo Youfeng, Untitled, 2020, altered vintage photograph Huo Youfeng’s mixed media works were begun just before, and during, the Corona lockdown. His latest work begins with an historical photographic image, which he obscures under a defiling layer of expressive paint. Youfeng (b. 1965, Heilongjiang, China) lives and works in Beijing where he was first renowned as a printer/lithographer, and influential as a teacher. In the US, he appeared most recently in Studio System 2 at the Torrance Art Museum. His photo manipulation work (here evidenced by a be-masked Leni Riefenstahl image of an Aryan youth) effectively melds two authoritarian layers, the idealized muzzled by a mask that provides both protection and imposed silence and anonymity. For those familiar with the Berlin Wall, and the art images associated with it, the pair famously embracing in “In the End, Isolation” will be recognizable under the masks: Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker, the former chairman of the DDR.

Huo Youfeng, 2020, In the End, Isolation, altered vintage photograph Youfeng writes: “In Western countries, normally only sick people wear face masks. This is the opposite of the East. The mask reminds people: ‘guard against the virus that could invade you.’ The face mask gives everyone a sense of security, but also a refuge from intrusion. In this way: everyone is equal. Whether it is a virus or racism, an individual or a great power, it is hidden behind non-hierarchically.”

Li Yang, 2020, Street a, digital photo Li Yang (b, 1983, Beijing) has a career spanning multiple decades and disciplines; he is best known nationally in China as a scene designer for opera and large-scale music events. Obviously, in the COVID-19 environment, all games are off in this profession. He turned to photography while quarantined in Beijing, creating a haunting series depicting the empty city. In his work for the theater, Li Yang is often charged with designing urbanscapes or environments, which for him creates a constant dichotomy between reality and illusion in his practice.

Li Yang, 2020, Street J, digital photo Wu Mengshi (b, 1986, Zhejiang, China) was educated at CAFA, Central Academy of Fine Arts) an important art Institution and museum in Beijing. Her kinetic works consist of skeins of delicate threads that cling and move nervously across a magnetized surface. Video available on:www.wumengshi.com.

Wu Mengshi, 2020 , Can, mixed media kinetic sculpture

Wu Mengshi, 2020 , Can, mixed media kinetic sculpture Both Mengshi and Wu Hong (b.1972, Beijing) have long ties to CAFA (Central Academy of Fine Arts), which alongside Tsinghua University, ranks as the most prestigious art academy in Beijing. Hong, who heads the Lithography department at CAFA, recently began this series of mixed media works tackling the issues of incarceration, animal treatment, and – metaphorically – of power itself.

Wu Hong, Caged 1, 2019-2020, ink, paper, security grill

Wu Hong, Caged 2, 2019-2020, ink, paper, security grill The personal work of Jenny Tang is represented here, by two photographs that relate directly to the quarantine. Normally her métier is lithography, but the crucial equipment is as locked-down as the people. Tang was trained at Tsinghua Academy of Arts and Design, and has exhibited in, and curated for, that institution. Tang writes: “To overcome fear and anxiety, I observe the surroundings with my eyes, and perceive my feelings with my heart.”

Jenny Tang, 2020, Untitled, photograph

Jenny Tang, 2020, Untitled, photograph -

SHELTER-IN-PLACE: Carolyn Campbell Explores the City of Immortals

Both cemetery and museum, the often-explored Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris is a stunning open-air space filled with dazzling sculpture as well as architecture. At over 107-acres, it is can also be exceedingly difficult to navigate, this burial ground of highly celebrated artists, writers, and performers.

Some visitors come to pay homage to the famous and revered, others to meander through the stunning collection of sculptural art, and still others to simply revel in the atmosphere of it exudes of both peace and majesty. Regardless of the reason for a visit – or an armchair trip – each visitor would do well to start their exploration with Campbell’s book, City of Immortals. It’s a thoroughly absorbing and enjoyable read, as well as a monumentally inclusive view of the cemetery from the date it was founded in 1804 to today.

Just as Pere-Lachaise is many things to many people, so too is this book: with a richly comprehensive map, a devouring curiosity about history and the magic the cemetery contains for its visitors; it is a guide, history lesson, and fascinating look at a location which could take almost a lifetime to fully explore.

As a writer and photographic artist, Campbell does the vast scope of the place justice with over 100 color photographs as well as historical lithographs, and detailed map. It’s a guide that not only points out some of the most famous spots in the cemetery, but provides a path through an almost labyrinthine location that can exhaust even the most intrepid visitor.

Having visited many years ago, the magical and mysterious quality of the cemetery is indisputable. However, for the casual visitor, it can also seem overwhelming. It is a Louvre for the departed. With that in mind, City of Immortals is more than a practical guide. It’s a roadmap through the past, and present, a way to delve deeper into a what is a true city of the dead, with the spirits of iconic and innovative creative voices almost palpable.

More prosaically, the book offers an insightful look at what was a highly innovative design for memorial grounds when first established. But best of all, this is a chronicle of Campbell’s own personal visits to the cemetery over a period of some thirty years. Offering three different “tours,” and a focus on 84 of the most famous gravesites from dancer Isadora Duncan to composer Frederic Chopin, poet Gertrude Stein, and artists such as Modigliani, her photographs are lushly, lovingly detailed; and in addition to her own, works by the U.K.-based landscape photographer Joe Cornish, compliment them. In depicting these works of sculptural art, they are art themselves.

In short, Campbell’s first-person account of the cemetery is quite wonderful. Her absorbing and comprehensive knowledge of the memorial grounds makes full use of her visits to the location. A viscerally entertaining and absorbing read, particularly in these pandemic times, it is comforting to “meet” those who have passed before us. It is also a thrill to explore what is arguably a different realm: not just a magnificent homage to the departed, but a special place, difficult to traverse without a map, enormously rewarding for those who do.

Released by Goff Books, peruse the map for future in-person visits, and in the meantime, take a stroll by proxy through The City of Immortals.

-

Quarantine Q&A: Andi Campognone of MOAH

Is your museum still open and operating with certain staff members coming in to work?

We are closed to the public but we are definitely still working. We understand losing income is real so we gave our staff new assignments and tasks so they would still receive a paycheck. Many of them are working from home. This closure has actually been a very productive time for us. We have managed to complete some long overdue maintenance and upgrades to our galleries and it has challenged all of us to think outside of the box on ways we may continue to serve the community while our buildings are closed.

Andi Campognone.

MOAH Staff Emily Krebs completing condition reports. Are you in touch with your members, fans and donors? Are they still interested in going to the museum or your programming or are they showing hesitation due to their finances due to the stock market slump or fears of the virus?

Honestly, I was pleasantly surprised to see so many of our members and donors renew their memberships and additionally make donations to our Artist Relief Fund.In your opinion, how long will this temporary shutdown of the LA art world last?

MOAH plans to be open by July, maybe before that, but we will definitely be implementing some new policies and procedures during our open hours, including staggered/timed entry, lowering attendance limits in galleries, providing multiple sanitation stations throughout the museum, requiring gloves, masks and other protective equipment for staff interacting with the public, requiring visitors to wear masks, posting signage requesting/reinforcing social distancing behavior for visitors and discontinuing large group events like public receptions, performances, etc.

MOAH’s Young Artist Workshop take home craft kits. How are you overcoming the challenges we are now facing?

This is an excellent time to reevaluate the effectiveness of programs, community engagement and exhibition opportunities. Obviously the virtual exhibition is an option but not really a new idea. We will continue our regular video presentation of all of our exhibitions on our website but with feedback from our artist community we realized other opportunities are needed. We have partnered with Destination Lancaster for our annual juried exhibition, which will obviously be online this year, to offer paid opportunities to artists for their work that will be used in the promotion of Lancaster as a travel destination. The artists will receive a stipend for the work and the art will be dispersed through marketing campaigns in the form of postcards at trade shows, in hotels and at the visitor center. We are also expanding our monograph and catalog publication program to include some fun options for both artists and visitors like all ages coloring books. We reinvented our monthly Young Artist Workshop to a weekly free take home craft kit for parents with children at home looking for educational activities. This program regularly served around 50 families monthly. Now we are serving 300 families a week with these fun take home kits. Also, with families in mind, MOAH staff developed a children’s YouTube channel @JoshuaJackrabbit complete with dozens of workshop videos and will soon include our educational trunks too.

MOAH staff member Kacey Manjarrez designing marketing campaign. How can Artillery’s readers help museums and artists while they are closed?

I think the obvious response here is to donate money if you are able. We are fortunate that MOAH is a municipal museum and we have a very strong fundraising Foundation that supports our programming. We are not forced to rely on donations to operate which puts us in a unique situation. However most museums do rely on donations for operations – give if you can and buy art! There are a number of affordable art auctions online right now that are supporting artists in need.

MOAH staff Emily Krebs, Carlos Chavez and Andi Campognone laying out art for upcoming show. Some art professionals are optimistic, and others worried. How do you feel? Is there anything surprisingly positive you have noticed so far? Or something you feel you or we all could learn from this?

I have been working in this industry for over 30 years and I have never before experienced the kindness, generosity and spirit that has appeared in the last month. Community actually means something right now, it’s beautiful to see. It’s great to see artists helping artists, businesses helping businesses, all creating a sense of hope that is palpable. I am proud to be a part of this community. -

COVID-19 Mask Contest

Inspired by @yrurari‘s mask we saw on Instagram, we called LA artists to submit their own mask creations. Submissions were either designed as a workable COVID-19 mask for daily use or as a creative endeavor at home while another face covering was used for safety outside of the home. We were thrilled and entranced by the entries. The level of craftsmanship and thought was beautiful to see during a difficult time for the magazine and the world. It seems that LA artists have not let the pandemic stop their work, if anything it is even stronger and more concentrated. We know it is a cliché, but our Editor in Chief truly had a difficult time choosing. Below are the winners and all entries. The two winners win a 2-year subscription to Artillery, exposure on our weekly newsletter and on our social media channels, and of course, mention on our website.Thank you to the artists who graciously shared their mask art with us and for the hundreds of Artillery Instagram followers and Facebook fans who “Liked” the entries and who spread the word about the contest. Please follow us on Instagram at @artillery_mag.Be careful out there and enjoy all the glorious mask art below.—Anna Bagirov, Publisher

MARISSA MAGDALENA, @marissamademe OTHER SUBMISSIONS

Carlson Hatton @carlson hatton Melora Garcia Kelley Benes @beansofohn Natalie Obermaier @kobramaier Carmen Mardonez @desbordado Julia Layton @j.y.layton. Elisa Ortega Montilla @elisa_ortega_montilla Corina S. Alvarezdelugo @justcorina_studio Nicole Belle Greta Waller @ashleydrusilla Owen GH Bradley Greer John Bagley Alonso Garzon @thehandofgarkhan -

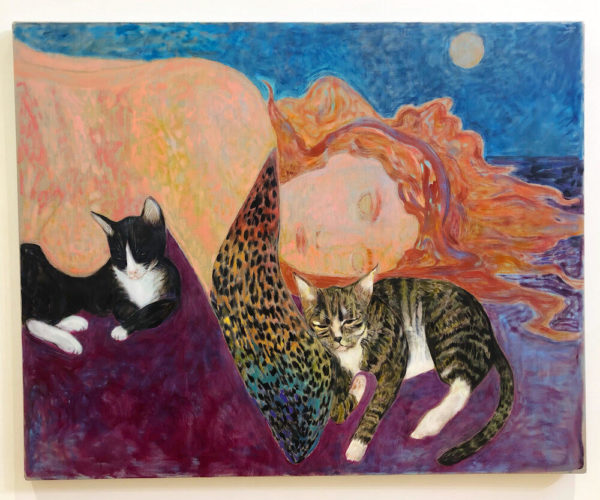

Women in Repose: Hayley Barker

We are in a time of global pause. A moment where everyone for the most part, is by mandate, confined to their interiors, forced into slower, humble domesticity; those with children are responsible for lessons, many are taking up culinary endeavors, and for the ambitious, some home projects. With very little chance for public presentation—save dressing oneself for afternoon strolls around the neighborhood with precious little dogs—it feels as if suddenly the world has been propelled into the traditional feminine.

In looking through photos friends share of their long, amorphous days lounging in their homes, I’ve been reminded of scenes rendered by Frederick Childe Hassam, The New York Window (1912) comes to mind, Joven Decadente (1899) by Ramon Casas, really anything in a room by Wyeth. If we find ourselves hungry for complementary images of women in repose, art can lift up its hoop skirt and reveal a bounty of paintings over the centuries. And because of this, and the conditions in which we’ve found ourselves, I’ve returned to the book by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space and what he calls “the imagination of repose.” In “House and Universe” he notes for Baudelaire, for the dandy, for the opium-eater, interiors are a chance for “an artificial paradise”—Bachelard writes, “if while reading we accept the daydreams of repose it suggests… it soon brings tranquility to body and soul. We feel that we are living in the protective center of the house in the valley. We too are ‘swathed’ in the blanket of winter.”

The River 3. 22.25x 20.25,” (2020). Oil on linen. Courtesy the artist and Bozo Mag. Repose here offers a balm, a comfortable space in which to dream, opium-induced (if we’re lucky) and decadent; repose is, I would say for men, the comfort and allowance of an invisible mother, to lounge and to think and create as one pleases.

But repose is, and has always been, more charged for women.

Hayley Barker is an LA-based painter, raised and educated in the Pacific Northwest, gaining well-deserved attention recently. Her first solo exhibition is upcoming at Shrine NYC this fall. When I visited Hayley Barker’s studio in late January, pre-pandemic, we spoke about just this. Can a woman ever really rest?

Barker taps into the implicit, frenetic energy of the classical female pose—how precariously they sit—and through her splendid use of color and brushstrokes, all the activity of sitting still. One feels the energy of a clenched toe, a bent leg, as the figures maintain their position.

One of my favorite paintings of hers, River 3 (2020) features a nude female figure in the foreground, seated on the trunk of a tree at the water’s edge; the rest of the work is distant cliffs, waves, and leaves—a Romantic’s Eden. The figure has her arms up, to precariously rest her elbows, a diaphanous robe slipping down across her lap; her gaze is demure as her head turns down fixed on her one foot dangling just above the water’s surface. The combination signifies the Classical woman—nude, posed for viewing, in nature—and yet, what prevents her from sliding down the rock if not tight muscles, hyper-vigilance, or the cleverest detail of all, the figure’s finger poking into the side of the tree?

What instantly compels the viewer in Barker’s oil paintings is color. She employs a pastel palette with flourishes of neon; these electric hues enlivening idyllic scenes from our art historical repertoire plunge us into anachronisms—what could be a field for Roman goddesses is now rendered with colors that remind us of the byproduct hues from labs and factories, from man’s clever creation-as-destruction—deadly, poisonous and alluring. I commented on her use of radioactive color admiring the atomic sherbet and chemical-leak lime: “It’s as if a bomb has just gone off or will. These could just as easily be impending doom or post-doom.”

Barker confirmed the intense feminine anxiety embodied in the figure in River 3 and her work as a whole. I asked her if she found the word apocalypse in relation to this charge in her work, a ridiculous term, or rather a male term, something too external; my feeling is that many women exist in aftermath. That the “bomb” is really our own experience with our bodies—moving through sexual assault, miscarriages, endometriosis, hysterectomies, giving birth, orgasms and aging. She agreed, and we laughed for a moment that women don’t need alien invasions, explosions and martial law in a dystopian downtown to feel destruction at bay; writing this in April, I would add, nor do we need a pandemic. Barker said her work involves addressing and healing from trauma, but healing is not calm, and should not connote placid faces and banal serenity. Barker is intent on capturing the chaos of integrating both painful experience, and the illumination born of inner work and spiritual practice.

Swimmer, 20.5″ x 25″ (2020). Oil on linen. Courtesy the artist and Shrine Gallery, NYC. Considering this, the anachronisms of her work move beyond aesthetic play and serve to capture experiencing time in a new way, or rather, a way that rings truer. I asked Barker if we might indulge a term like “female apocalypse,” and if so, did she feel it existed outside of an isolated event: was the female apocalypse ever-present? Barker expressed, what matters most is the fluidity of time for women, made more apparent when set against nature, as the beautiful must also contain complicated things, violence and disorder, so in this way: it is happening, has happened, will happen at once.

Because the lounging figures in Barker’s work appear active, they command our attention. Like Matisse’s Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading) (1906), we witness their interior world spilling over, and radiating out. But with Matisse’s figure, I feel separated from the girl, that what is being radiated from her is—if not veiled from us—still very quiet; Barker’s figures are here to have us look and let us know; they are in radical opposition to the derisory epithet I hear all-too-often of women who are “too much.” Barker told me, personally she is embracing this phrase, inviting in her shadow self, and allowing being “‘too much” to serve as a kind of superpower. Thinking back to Barker’s Bozo Mag exhibition in 2017, and the series of faces she showed, I was reminded of one titled Extra.

The concept of being a little “extra” means embracing the very qualities women have long been shamed for: loud, indulgent, commanding of space. In the world of social media exchange, it might be an image of Rihanna walking down the street with an oversized wine goblet or Maria Callas as Medea with the caption “mood.” Being extra is about being monstrously female and reclaiming it. Considering this, it is of no surprise that Barker is influenced by Kristeva. Barker’s drawings especially are about embracing the monstrous. As Julia Kristeva’s 1980 book The Power of Horror opens:

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated. It beseeches, worries, and fascinates desire, which, nevertheless, does not let itself be seduced.

In 2017, Barker, in collaboration with LA gallery Bozo Mag, published a book of Bed Drawings: Dark Goddesses, Queens, and Swamp Things a companion publication to her “Open Studio” Exhibition. The book contains eight 6-inch drawings, black marker on paper, all done, as the title suggests, from bed. Barker explained how important this morning ritual is to her art. To work in the early hours, in the same spot she sleeps, to grasp onto a liminal state a little longer, recall dreams, and revive the images is both therapeutic and generative. For Barker, and for women, the bed, perhaps the greatest symbol for intimate space, is not “swathing us” in rest in comfort from the outside, but a space for confronting and plunging psychic depths and claiming whatever surfaces, in this case compelling and horrific and lovely monster faces. The abject made manifest.

“Some Shade,” 25″ x 20.25,” (2020). Oil on linen. In Barker’s painting, The Next Time You See Me… (2019 Oil on Linen) we behold a grotesque profile, blue eye fixed at us, hooked nose, sour bottom lip, and wild cotton-candy hair. The title, I think, is a threat; that the phantoms return, that the next time we might we might appear unrecognizable as we tiptoe towards assimilating our complex feelings of attraction and revulsion to our most hidden parts. Barker, as if reading my thoughts completes the title’s ellipses: “…I Will Be 1 M Times More Beautiful.” The greatest threat of all: monster metamorphosis and the concealed shadow of beauty.

As the world outside coughs up another clever meme on “Waiting Out the Apocalypse” and laments the unbearable restlessness of rest, I keep returning to Barker’s paintings and thinking about the homeless, frenetic energy of a human body staying still.

I called Barker this week, to congratulate her on her online group show with Shrine NYC , “Connections,” and to ask if anything has shifted in her practice with the recent stay-at-home orders.

She said, “the realm of the intimate, of self-reflection, psychological states; the relationship with oneself and with other women, the earth and art history is finally on the radars of others. One result is there more appreciation for the subject matter. The world, forced to go slower, is more tuned into notions of healing from trauma. There is I feel, a broader relevance to my work.”

The stunning paintings of Hayley Barker reimagine the woman in repose. This time she has embraced the terror of pre-doom and post-doom and rests, not as a retreat, but as a radically deliberate act: as one radiating triumph in stillness.

Hayley Barker: https://www.hayleybarker.com/

-

SHOPTALK

Pomp & Zoom

Spring usually heralds a spate of art-school grad ceremonies and shows—the equivalent of debutante balls for young artists and designers trained at our august art schools. This year with shelter-at-home and social-distancing mandates in place, there will be no crowds gathering in an auditorium or on a sun-speckled lawn, no mounting the dais as your name is called out, no booze-fueled grad bash before or after.

However, with current technologies, there will be Virtual Ceremonies, and Art Center College of Design, CalArts, and the Roski School of Art & Design at the USC have jumped on that bandwagon. Roski is calling it a “celebration,” since they’re inviting grads to a future RL graduation—though it looks like others are, too. As of this writing, Otis is not having commencement this spring, virtual or otherwise, also inviting grads to come back for a later ceremony with a future class, and no one from UCLA responded to this query.

So how is it going to work? This morning, May 2, I watched the first ceremony on the calendar—that of Art Center, and it ran remarkably smoothly. (Disclosure: I’m an adjunct prof there.) It opened with President Lorne Buchman giving a pithy but so very pertinent speech, calling on the graduating class to rise up to the challenges ahead—and such challenges they are. As he said, “The space of uncertainty is the space of creative engagement.”

Then department chairs introduced their department and graduates, with sample work shown. The final half hour was a kind of Zoom-in bash, showing clips of attending grads from homes and personal spaces, some with families and friends celebrating with them, several holding up their pets. They were waving, they made “peace” and “heart” signs with their fingers, they were dancing to the beat of the background music. So unexpectedly, this was the most personal and moving grad ceremony I’ve ever attended. It’s the courage of youthful optimism in the face of this pandemic, it’s the power of Zoom—the power of being able to see people in individual environments, and in closeup.

Johan Andersson, Frontline, 2019 Venice Family Clinic Art Auction

The Venice Family Clinic’s popular annual auction will go on. This year they’ll dispense with the art walk and go directly online—May 3–19 on Artsy https://www.artsy.net/auction/venice-art-walk-benefit-auction-2020—to sell art to raise funds for the clinic’s COVID-19 response. Over 150 artists have contributed work for the auction—you’ll recognize many names on the list. This includes prints by Renee Petropoulous and Ed Ruscha, paintings by Kelly Berg, Astrid Preston and Kim Shoenstadt, and sculpture by the Haas Brothers and Ramona Otto. There are also several art talks scheduled. Check out the auction catalog and programs at https://venicefamilyclinic.org/annual-events/venice-art-walk/

Vanessa Prager, Solitude in Pink, 2020 The clinic serves an area which, despite its groovy reputation, has a population with 75% at or below the poverty level and 16% homeless. Yes, sadly, you see the street by street homeless encampments when you drive through Venice these days. The clinic provides much–needed medical and mental health care services, and also helps with access to food and housing, regardless of patient income, insurance, or immigration status. It’s a worthy cause, ladies and gents!

Jeffrey Deitch Gallery Platform LA

You’d think there would already be an LA gallery association, and over the years I’ve heard of galleries at Bergamot Station and Culver City coordinating to time openings, publicity, etc. However, the dire conditions brought about by what I’ve called Q-Time has prompted galleries to band together to promote themselves and the art they represent. Initiated by NY/LA art dealer Jeffrey Deitch, 60 Los Angeles art galleries are coming together for an online platform — Gallery Platform Los Angeles (or GALA) to be found on galleryplatform.la. Every week starting mid-May they will be presenting “viewing rooms” from 12 galleries. These will offer works for sale, along with videos on artists, collectors and gallerists—basically what many galleries are now doing, except individually on their own website. While the “viewing rooms” will rotate, editorial material will remain.

“I think there’s a great sense of community in Los Angeles,” says Elizabeth East of L. A. Louver, “and we’re now in this new reality of working with our audience over a variety of platforms. We are disperse, but in some ways this is a way of bringing us together in cyberland.”

Later the group will also produce joint programming, gallery maps and other projects. Currently, membership is free, although it’s vetted through a coordinating committee, which includes big galleries such as Deitch, Blum & Poe, Gagosian, Matthew Marks, and Regen Projects, as well as smaller ones such as Bel Ami, Jenny’s, and Various Small Fires. Platform coordinator Nicoletta Beyer says that designing and maintaining the website will be funded through “fundraising internally.”

Authors Note: By the way, this is not to be confused with a website sponsored by David Zwirner called “Platform: Los Angeles.” That’s featuring 13 galleries, and is part three of their “Platform” series, the first two featured New York and London galleries.

Goings & Comings

Sadly, this will be the year of far more goings than comings. An April survey of art galleries by the LA Times culled 35 respondents, with nine of them saying they faced permanent closure unless a fast recovery is around the corner. Not surprisingly, since 89% of them reported reduced sales since the shutdown. Frankly, I am surprised the figures aren’t 100% —perhaps something to do with sales already underway? Remember, we just came off the high of Frieze LA 2020 and the other fairs taking place the same weekend, when a number of galleries reported excellent sales. According to the LAT survey, over half the galleries have retained their staff, although we know that many galleries operate on shoestring staffs—the owner and maybe one or two employees.

Some good news: museums in other parts of the world are reopening, such as those in South Korea and Germany. Germany has some 170 state, municipal, and private museums, and a number reopened end of April and many more will by early May, with precautions in place. I’m not in a rush for SoCal museums to do the same, but suggesting looking at what happens in Germany for a way to go forward. Another place to look is Hong Kong International Airport, where they’re testing cleaning robots and disinfection booths.

Bye for now—look forward to seeing everyone in RL soon, soon!

-

ART BRIEF

The saga of British art dealer Inigo Philbrick is testimony to the pitfalls of the trust and handshake deals that have become customary at the highest levels of the art world. The fall of Philbrick—a protégé of Jay Jopling, the principal of London’s most prestigious art gallery, White Cube—sheds light on fast and loose practices of high-flying dealers, such as buying and selling fractional shares in artworks and price guarantees at auction. Faced with at least three lawsuits involving him and his company, Philbrick has now fled to parts unknown.

Philbrick, 32, came to the art world with a fine pedigree: his father had been director of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut, his mother teaches at Parsons School of Design. Philbrick attended Goldsmith’s, University of London, an art school. Jopling, also a Goldsmith’s graduate, hired Philbrick as an intern at just 24 and within a year he was made director of secondary market sales at White Cube. He sought to go off on his own and in 2013, with financing provided by Jopling, he opened Inigo Philbrick Gallery in Mayfair where he also resided. Philbrick lived a flashy lifestyle sporting bespoke suits and expensive jewelry, and dating a popular reality TV star soon after his partner gave birth to his child.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2012. Philbrick dealt primarily in secondary art market sales and specialized in works by Yayoi Kusama, Mark Bradford, Wade Guyton, Christopher Wool and Rudolf Stingel. He claimed to be an expert on Stingel and it would be his photorealist painting of Picasso that first got Philbrick in trouble. He bought the painting in 2016 for $6.7 million with his friend Sasha Pesko, who put up half the funds. Philbrick who was used to quickly flipping art, held onto the Stingel when he couldn’t get anyone to buy it for his asking price. When it finally sold at Christie’s in 2019, it only realized $5.5 million. After the sale, all hell broke loose when it appeared that Philbrick had sold an interest in the piece to buyers other than Pesko. According to The New York Times, the other investor in the Stingel was Fine Art Partners, which had previously invested with Philbrick in works by Wool, Guyton and another Stingel. But the market for these three artists declined and Philbrick could not make quick flips of their works.

According to the Times, Philbrick showed Fine Arts Partners a guarantee by Christie’s on the Stingel painting for $9 million. After the disastrous sale, Philbrick assured them that Christie’s would make up the $3.5 million deficit because of the guarantee. When the money was not forthcoming Fine Art Partners contacted Christie’s, which examined the guarantee document and determined that it was probably a forgery. Then things got even worse. Christie’s general counsel told Fine Art Partners that Philbrick was acting as a representative of Guzzini Partners, an art investment company controlled by the Reuben brothers, renowned art collectors and one of the UK’s richest families. According to the Times, it turned out that Guzzini paid Philbrick $6 million in 2017 as part of a group sale including the Stingel. To top it off, the winning bidder at Christie’s was a dealer who was bidding at the direction of Philbrick to protect Pesko’s interest. The dealer paid Christie’s only $2.35 million and Philbrick failed to pony up his share of the money.

Philbrick had opened an art gallery in the Miami design district. That was the venue where Fine Art Partners filed suit against him. On the day he was due in court, his lawyer quit the case. Philbrick did not appear and has not been seen since. His Miami gallery was padlocked.

Wade Guyton, Untitled (Flaming U, Red U, Yellow Flame), 2011 The Times reported that with Philbrick on the lam, the Reubens brothers, through their company Guzzini, sued the Stingel painting “in rem,” (an action to determine rights to property) asserting that their claim took priority over the interests of both Pesco and Fine Art Partners.

At least two other lawsuits pending involve Philbrick, one by Pesco filed in London concerning a major Basquiat painting that Philbrick allegedly sold twice, the other concerning a Wade Guyton painting, “Flaming U,” against the Reubens’ company Guzzini by another putative buyer.

This is the sad tale of a high-flying art dealer who thought he could take advantage of the frenzy among the wealthy to flip art. The problem for speculators is that when they buy fractional shares in an artwork, they usually do not take possession, giving rapacious dealers such as Philbrick the incentive to conceal the actual amount of investments in the work. It’s estimated that Philbrick’s schemes have cost art investors well over $100 million.

-

DECODER

You could draw people in masks. Paint them. Paint on them. Make videos where the face above changes but the mask does not, challenging the viewer to notice and read the eyes, the hairline. You could fashion new masks or sculpt respirators. And the gloves, too: photograph the wet slack way the human hand, medically gloved, becomes reptile now.

It might be within a stones’ throw of what you were up to anyway, all the years you spent in school and then after looking for your exact thing. It might speak to your established themes as they say. There might be a virtual group show about it, the virus, and you might be in it because you made the art with gloves and masks.

It might be a slow day at some paper, some site, someone’s twitter. They might go “Wow the art about the people in masks? That’s The Art We Need Right Now.” You might get in. For the first time—noticed—because you made the art about the right horror at the right time.

People will ask: How did it hit you, this image? The lower half of the face erased. Are they bandits? Doctors? Antifa? Terrorists? What does it mean to wear a mask? Are you a futurist now?

Some foundations and funds will get involved, and independent and, if you’re lucky, wholly-dependent curators. You have this whole room, floor, gallery to yourself. Have you ever been to Paris? Welcome!

In months or years we’ll have moved on to a new crisis, but you’re in, and that’s what matters. People have invested in the idea that you’re good. Having waterskied in holding tight to the Topic (no shame in that, we all have to work the inadequate lanes they give us) you now have to bring Topics to you. Convince people your latest obsession is as relevant as your last. Those masks? All part of a bigger mythology, see? Now I’m doing anatomies, barrels, ears, noses and throats.

Art is always supposed to be responding, reacting, expressing what’s changing, but artists who are most sensitive to those changes or enamored of those changes or just plain willing to exploit temporary public fascination with them have a tricky path. Art is slow and the news is fast—although there’s always art willing to respond to the big-T topics and there will always be column inches devoted to that art, the most celebrated art is never that. Fairly or unfairly the incisive, insightful, thought-provoking, specific and above-all fast reaction to 9/11 or Katrina or Corona never quite makes it onto the decade’s Top 10 lists.

War memorials get close (there will always be another war): Guernica by being, let’s face it, vague and the Vietnam Wall for proving ordinary people might have a use for minimalism, but the top spot is usually reserved for something that cuts obliquely across a decade of headlines, capable of somehow answering the anxieties of any number of curators.

Deep down, this rests on the assumption that life is slow: of a piece, summarizable, full of thoughts absorbed here that are also useful there. And art, being slow, has thrown in its lot with this view: you can’t do everything, everyday. You back up and take life at a distance.

And art is getting slower, relatively, because its done in the face of a metastasizing variety of creativities that touch the news closeup, responding fast, one topic and then the next, one season and then the next, a meme and then the next. The culture at large has never had a faster response time or such a rich toolkit with which to design those responses. We will never win a contest of quick wit.

When I say art is slow that isn’t a value judgment in either direction: the lone, unsupported human making a thing to be shown in a special room months or years after it was conceived is the baseline pace for fine art. Is that how life works still? Life might actually be unsummarizable, and the only universal experience might increasingly just be: One thing and then the next.

When asked what art is doing in the face of this crisis or the last one we should also ask why so often we just can’t do crisis. To choose fine art is, for the most part, to choose to be slower than anything you might call a “response.” Let’s make sure we’re making that choice consciously. Do we love what is slow for some reason other than wishing this up-to-date life away? And what uses do we put our slowness to?

Illustration by Zak Smith.

-

ASK BABS

Dear Babs, As an artist practicing social distancing I’ve begun feeling guilty for not doing more with all this new free time. I look on social media and everyone is being so productive, making art, and learning new skills. I’m not making art or much of anything. Should I feel guilty about my laziness? —Lazy in LA

Dear Lazy in LA, There’s a self-help industry out there filled with advice about how to get your creative mojo back. If you are expecting me to regurgitate the truisms from that life-coaching morass, I’m sorry to disappoint. Read Julia Cameron’s timeless book The Artist’s Way and see if that helps.

What I really want to suggest is that you use this opportunity to consider what your “laziness” actually is and question why you feel guilty about it.

Given that America brands itself under the false pretense of hard-working exceptionalism supported by Horatio Alger myths and the lie of meritocracy that smooths over the bleak reality of systemic inequality and the evils of unbridled capitalism and corporate greed, it’s no surprise most of us feel guilty when we don’t want to work, or in our current shelter-in-place realty, cannot work. To not work is far too often seen as evidence of a great personal failure. The expectation for constant production in service of growth, whether in the form of quarterly reports, lines on a CV, or Instagram approval for one’s self-actualization, certainly contributes to that feeling of paralyzing anxiety about being lazy you’re now experiencing. So it makes sense that people feel obliged to “make use” of this new “free time.”

Obviously not everyone is fortunate enough to experience the same sort of freedom, certainly not the workers on the front lines of the battle against the virus and the people who are keeping life itself afloat: the millions we rely on to heal, feed, clean and care for this reality we each inhabit with unequal resources and varying positions of privilege. Some people have to work; our free time is their overtime. It’s worth taking a moment to appreciate this fact before moving along, not to make you feel more guilty, but because we need to acknowledge that we are not “all in this together” in the same way. If volunteering to help out might get you out of your funk, then by all means do so. But also know you’re not obligated to make masks, fundraise or make art about the pandemic. All that is great, but as long as you’re doing your part to responsibly slow the spread of the virus you’re doing something.

If you want to make art, make art. If you don’t, then don’t. But please don’t fall into the trap of feeling guilty you’re not creating the next masterpiece or conquering Duolingo. Perhaps you’re learning to be okay with not being productive, and that in the end may be the most productive thing you can or should do.

-

BUNKER VISION

If you weren’t around for the 1970s, it’s a hard era to explain. And thanks to AIDS, there are fewer people left alive to explain the queer experience of that decade. Happily, there are movies. The reason that these movies exist is almost accidental. Budding auteurs, inspired by 60’s underground cinema, started shooting gay porn films in real locations. In many cases, the establishing shots look like they were shot on the fly by a lone camera person. Back when people didn’t routinely carry video cameras in their phones, a camera could draw attention, and when it did, it was more likely to be met with enthusiasm than hostility, especially if the cameraman looked like the people that he was filming. It’s worth noting that at least one of these filmmakers (Fred Halsted) has a film in the permanent collection of MoMA.

Evan Purchell is an archivist/historian who specializes in the culture of this era. His Instagram account @askanybuddy features advertisements and stills from films of this era. Most of the ads look more like punk rock flyers than publicity for any sort of commercial cinema. His Twitter account @schlockvalue is fun too. He uses that to showcase recent acquisitions and to share some jaw-dropping bits of monolog, dialog and shots of lost locations. He is currently in the process of making his debut as a filmmaker. Using pieces of 126 of these films, he has created a collage film that might be the best existing snapshot of the queer 70’s experience. People looking for something to compare it to, often come up with Christian Marclay’s collage films.

Still from Ask Any Body, 2020. Collage is one of those art forms to which many are called, but few are chosen. It is trickier than it looks to cause multiple power-laden images to interact in a way in which they become more than the sum of their parts. One of the wonderful things about the finished film is that Purchell employs his archivist sensibility to find subtle common motifs. Those three shots that you just saw of the same place might actually be from three different movies that were filmed in the same location. Many of these locations were either torn down, like the New York piers, or gentrified beyond recognition. Others such as clubs and bathhouses might have been closed. One of the things that makes this such compelling viewing is that many of these films were butchered for shorter running times, and to focus more on sex. By finding original prints, more of the lost history that was less titillating is available as documentary footage of the era (the earliest film dates from 1968, and the latest is from 1986). Although he doesn’t shy away from the X-rated scenes, it doesn’t feel like this film is about them: they feel like a natural part of the landscape that they inhabit.

Still from Ask Any Body, 2020. The film opens with the warning: “For your enjoyment, do not try to understand this film, there is nothing to understand. It is only real people doing reel things and making them real together.” This is excellent advice. Fasten your seatbelts, and please keep your hands and arms inside the car at all times.