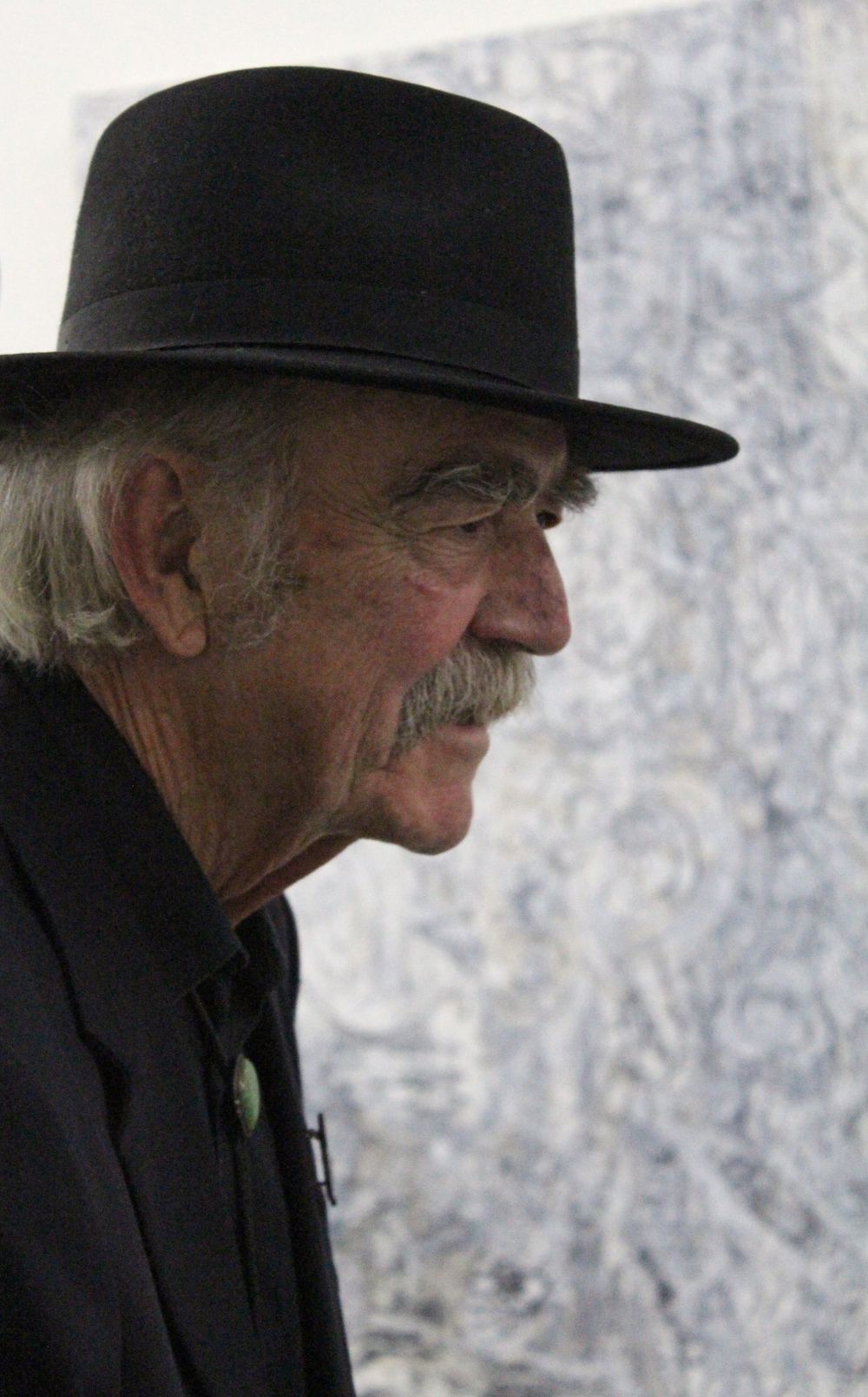

Influential Northern California artist William T. Wiley passed away on April 25 in Greenbrae, CA. His combination of irreverence and spirituality so keenly reflected the spirit of our times, where we don’t know quite what to believe, but would all like to believe in something good. Like Wiley, many artists have worshipped at the altar of daily art practice, with a Zen-influenced mindfulness as their guide. Always a champion for the causes of social and environmental justice, and with an infectious, if occasionally groan-inducing, pun-intensive, sense of humor, Wiley was one of a kind.

William T. Wiley @ Hosfelt Gallery, 2015

William Thomas Wiley was born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937, his family moving around a fair amount as his father, a construction foreman, took a succession of jobs. For a period they lived in Texas where they ran a combination gas station/diner, sometimes decorated with the young Wiley’s cartoons and drawings of horses. Later they settled in Richland, Washington where Wiley was encouraged by a prescient art teacher to pursue a career in fine art. This motivated his move in 1960 to the Bay Area to study at California School of Fine Arts, now San Francisco Art Institute. Wiley had a prodigious natural aptitude for art, and received a full scholarship to the school. Wiley also had a kind of low-key, hip disposition that was a good fit with the counterculture vibe of an era where the beatnik generation was giving way to flower children in San Francisco.

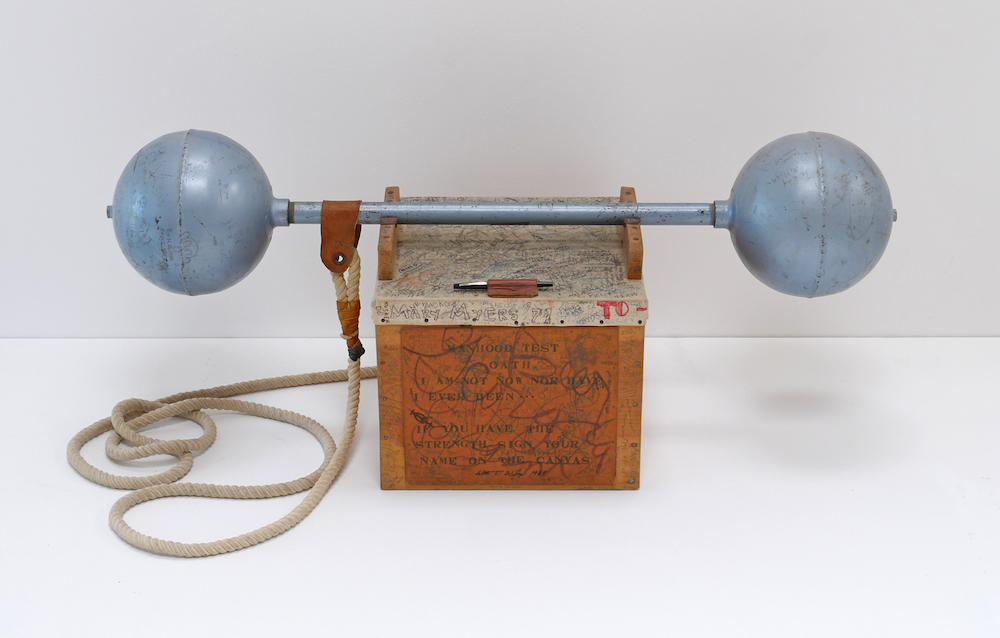

William T. Wiley, Manhood Test, 1969

San Francisco in the 60s was heavily influenced by the Beat scene, with writers like Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassidy and Lawrence Ferlinghetti reading their work in North Beach; words, music and art were closely intertwined. In addition to composing his poetic writing, which became enmeshed in the work, Wiley became part of a band, playing harmonica and guitar. With a breadth of media spanning painting, drawing, printmaking, assemblage and sculpture, one might well propose that his true calling was conceptual art. An enigmatic found object, Slant Step, acquired a talismanic significance in Wiley’s oeuvre. Former student Bruce Nauman, who later would himself influence the older artist, absorbed Wiley’s unspoken understanding that just about anything could, and would, be integrated into his art practice, and that the community of like-minded artists with whom he shared this journey were at least as important to him as the work itself.

William T. Wiley, Agent Orange, 1983

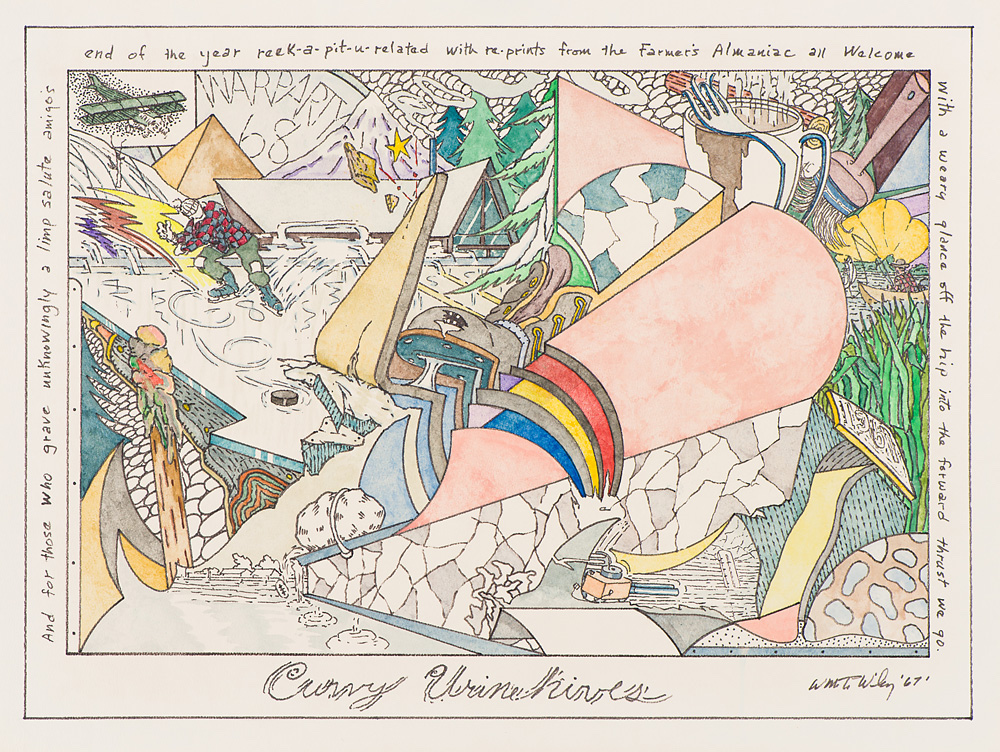

Almost immediately after graduating, in 1963 Wiley moved to Davis to accept a teaching job at UC where a critical mass of fine artist/teachers such as Wayne Thiebaud, Robert Arneson, Robert Hudson, Cornelia Schulz and Manuel Neri drew art students flocking to the sun-baked suburb west of Sacramento. The fiercely independent and quirky style of work created by Wiley and his cohorts came to be known as Funk Art, with its combination of casual and eccentric vibes, often displaying a bit of a rough-hewn esthetic. Venerable curator Peter Selz mounted a seminal “Funk” exhibition in 1967 at Berkeley Art Museum including Wiley, Joan Brown and Robert Arneson, among others.

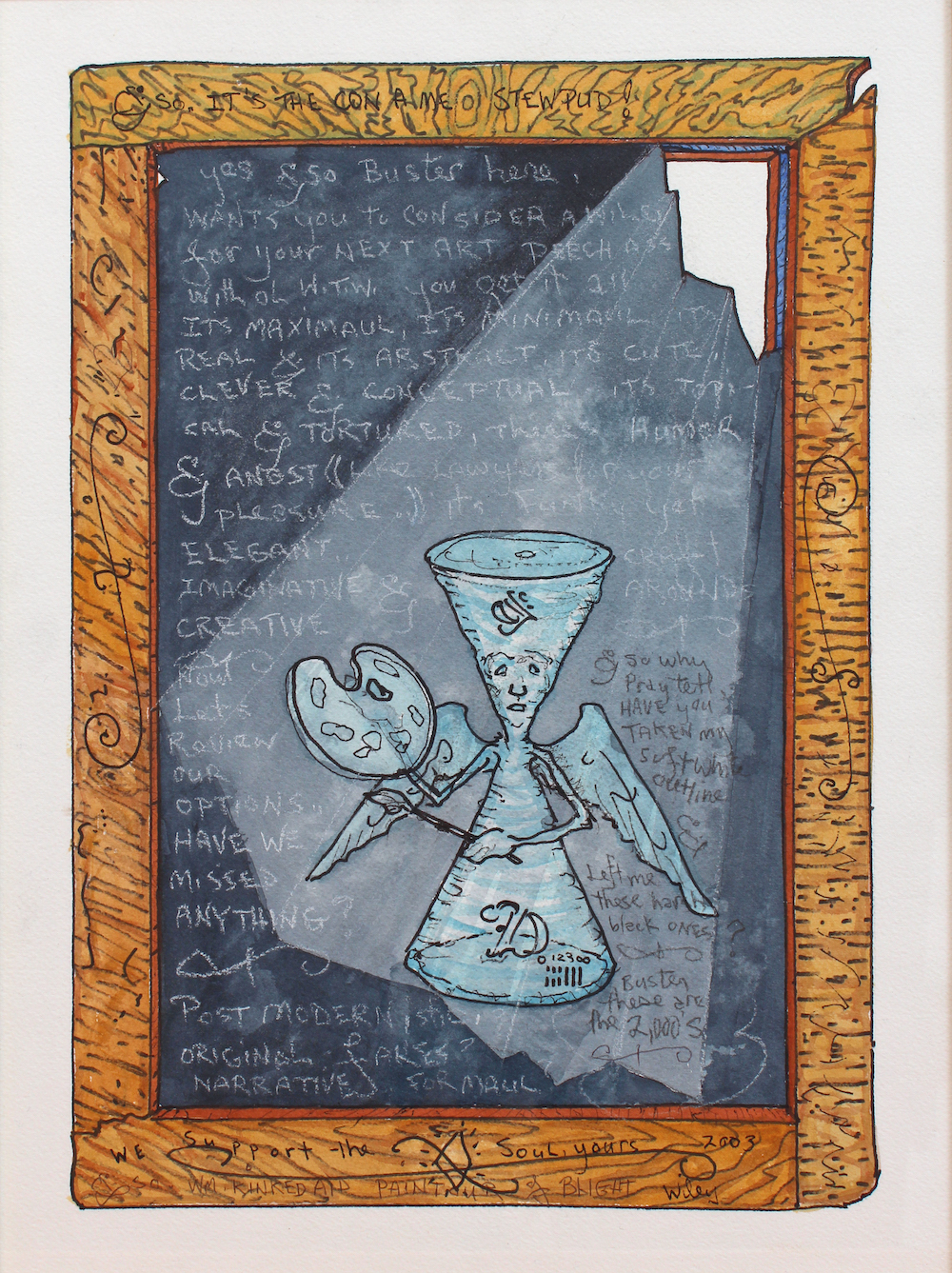

William T. Wiley, Buster in the Light, 2003

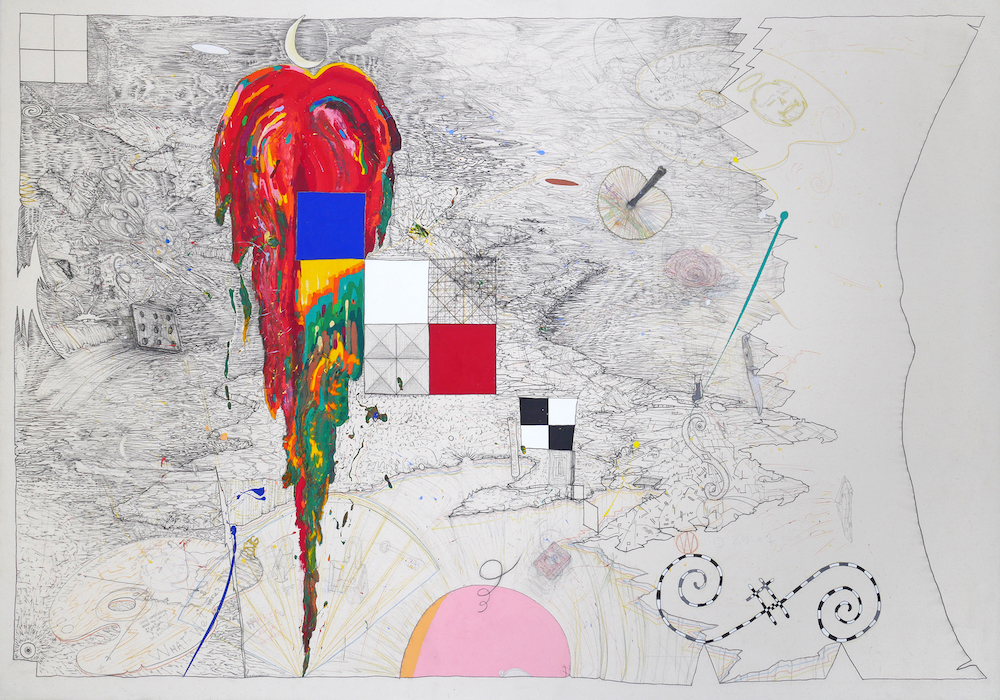

Wiley’s work often features an eclectic melange of Zen-inflected puns and spoonerisms, liberally scrawled across a variety of two- and three-dimensional surfaces. Often these take the form of landscape or still-life subjects, gardens with stumps or eddying streams, intertwining vistas of tools, still life objects, vines and plants, revealing his deep connection to nature and the kind of rural life where voluntary simplicity meets absurdist humor in an altered state of consciousness. With the ranches and farmlands of the rural west adjacent to where he and his cronies crafted meticulously-wrought, idiosyncratic artworks, his exhibition at SF’s Hansen Fuller Gallery in 1971 yielded a review in the New York Times where Hilton Kramer christened his style “Dude Ranch Dada,” a phrase that stuck.

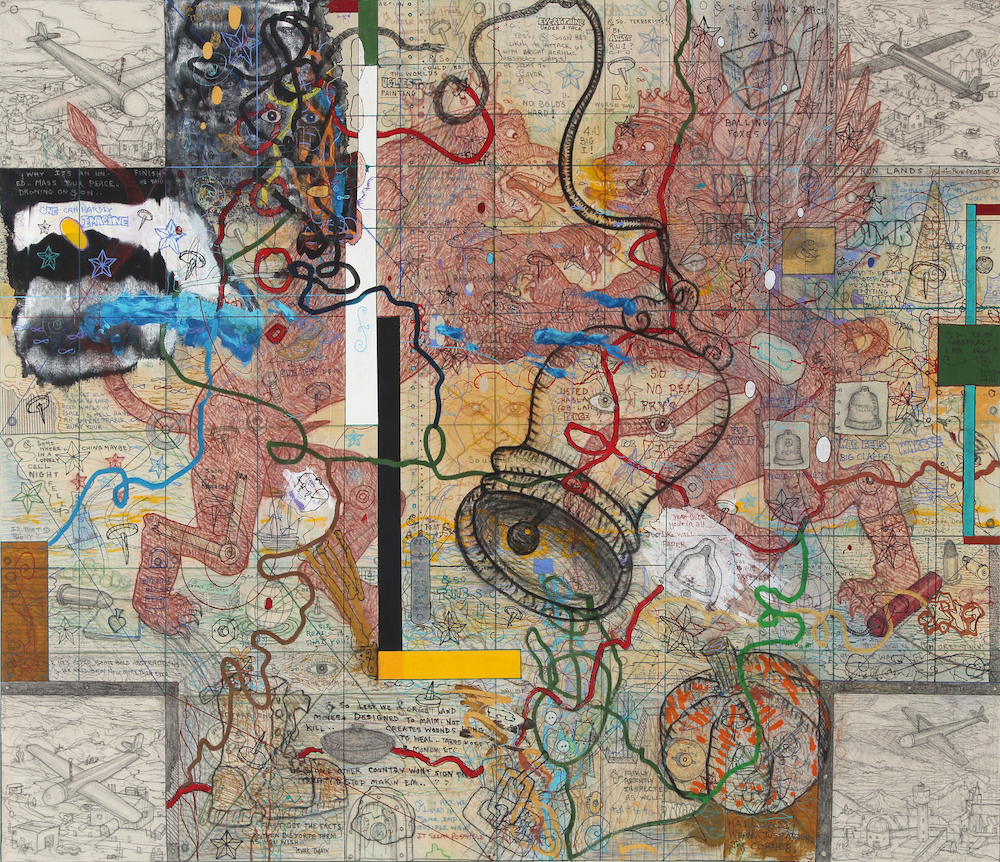

William T. Wiley, On the Left… We? Attempt a New Sign for the Palate. On the Right, Gold Man Sacks the World, 2010

Humor and jokes often propel the work, and Wiley constructed over the years a cast of characters that often act as autobiographical stand-ins. These include Mr. Unnatural, an affable, befuddled figure with handlebar mustache always wearing a wizard hat/dunce cap, and Buster Time, a winged hourglass who reflects on the fleeting nature of life. These characters could easily have stepped out of an underground comic, in fact, the truckin’ figure of R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural in Zap comix one clear source. His deep concern for mankind and the fate of the planet directly informed later works where he confronts existential issues such as war, pollution, racism, political malfeasance and general bad behavior, as well as an increasing preoccupation with his own mortality.

William T. Wiley, No Bell Prys for Peace with Predator Drone, 2010

A show of Wiley works curated from their collection is currently on display at SFMOMA. Wiley participated in numerous significant shows including Harald Szeemann’s “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form,” a 1969 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland that helped to define the Conceptualist and Minimalist art movements, the Whitney Annual and Biennial, two editions of the Venice Biennale, and Documenta V in Kassel, Germany. He had a major retrospective, “What’s It All Mean: William T. Wiley in Retrospect” in 2009 at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, DC, and a noteworthy, sprawling show at SF’s Hosfelt Gallery in 2014. The Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at UC Davis has a major exhibition of Wiley’s work scheduled for 2022, “William T. Wiley and the Slant Step: All on the Line.”

Wiley, who succumbed to complications of Parkinson’s, was predeceased by his younger brother, Charles, an artist at Industrial Light and Magic in San Rafael. He is survived by his wife, Mary Hull Webster of Novato, ex-wife Dorothy Wiley of Forest Knolls, his sons Ethan Wiley of Forest Knolls and Zane Wiley of San Rafael, as well as four grandchildren. Innumerable former students and colleagues also mourn the loss of this iconic figure.