When I first encountered Tim Youd, he was sitting at a metal table outside an art gallery in Chinatown, tap-tap-tapping away on a portable typewriter, just minding his own business. Most of the crowd didn’t pay him much mind either.

Earlier that summer, Youd found himself on the flatbed of a pickup truck parked in front of LA’s Terminal Annex Post Office retyping Charles Bukowski’s Post Office on an Underwood typewriter. That was in July of 2013 and proved to be a precursor to the LA performance artist’s ongoing “100 Novels Project” series, in which Youd visits the settings of one hundred novels and retypes them in their entirety on the same model typewriter that was used for the original composition. The Bukowski performance would become number 7, marking the beginning of these literary pilgrimages that would take Youd all over the world.

Now, almost a decade later, I’m in Red Cloud, Nebraska, to watch Youd (pronounced you’d) perform a retyping of Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. Speaking of larks: Could Youd have ever imagined his project taking him this far, literarily and geographically?

Tim Youd retyping Jack Kerouac’s Big Sur. Bixby Bridge, Big Sur, CA, July 2015, courtesy Cristin Tierney

“I think that’s the great good fortune that I have happened upon,” Youd tells me over an espresso at the one coffee shop in Red Cloud, a small prairie town of around 1000 souls. We’re marveling at his journey thus far. Just name any well-known American author—been there, retyped that: Kurt Vonnegut, Upton Sinclair, Jack Kerouac, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Tom Wolfe. Cather’s The Song of the Lark is number 72—only 28 more to go. What can 10 years of intense drive and dedication possibly mean at this point, other than perhaps I’m talking to a well-read madman. “This thing has become way more expansively meaningful to me than I could have ever imagined in the first couple of retypings,” Youd exclaims, pondering the meaning of it all. “It’s become my whole life. It’s become everything.”

Willa Cather & Red Cloud

I took it upon myself to read some Willa Cather before I went to see Youd perform, starting with O Pioneers!, then moving on to The Song of the Lark. I was quickly hooked, and going to Cather’s Nebraska hometown made the read that much more meaningful. Red Cloud was Youd’s second stop of “The Prairie Trilogy,” aptly named for his literary pilgrimage to three Nebraska cities: Lincoln, Red Cloud and Omaha, inspired by Cather’s own Plains Trilogy: O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, My Antonia, all books highlighting the presence of the Great Plains, a landscape that had an undeniable influence on Cather throughout her formative years and young adult life.

The National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud (co-sponsors of The Prairie Trilogy project) hosted my stay in the tastefully restored historic building. When I arrived late in the evening, Candace Moeller, director of the Cristin Tierney gallery in New York (who represents Youd and are co-sponsors of the project), was at the center, waiting for me along with Youd. Mueller bought two bottles of wine and whipped up a pasta and salad. Youd had finished a day of typing. I’d just come from LA. It was a perfect way to end the evening with so much mirth at the kitchen table. Our conversation always circled back to reading and literature, which is almost unavoidable if Youd is in the room. We all turned in before midnight; tomorrow would be a busy day.

The next morning, I set out to visit the Willa Cather house, where Youd would be typing. It was sunny but brisk as I walked down the main street. Shuttered businesses mixed in with open shops: one bank, the post office, pharmacy, food market, bar—and a Subway (!)—all lining a red-brick road, probably the same bricks that Cather rode down in a horse and buggy.

Youd at Willa Cather’s childhood home.

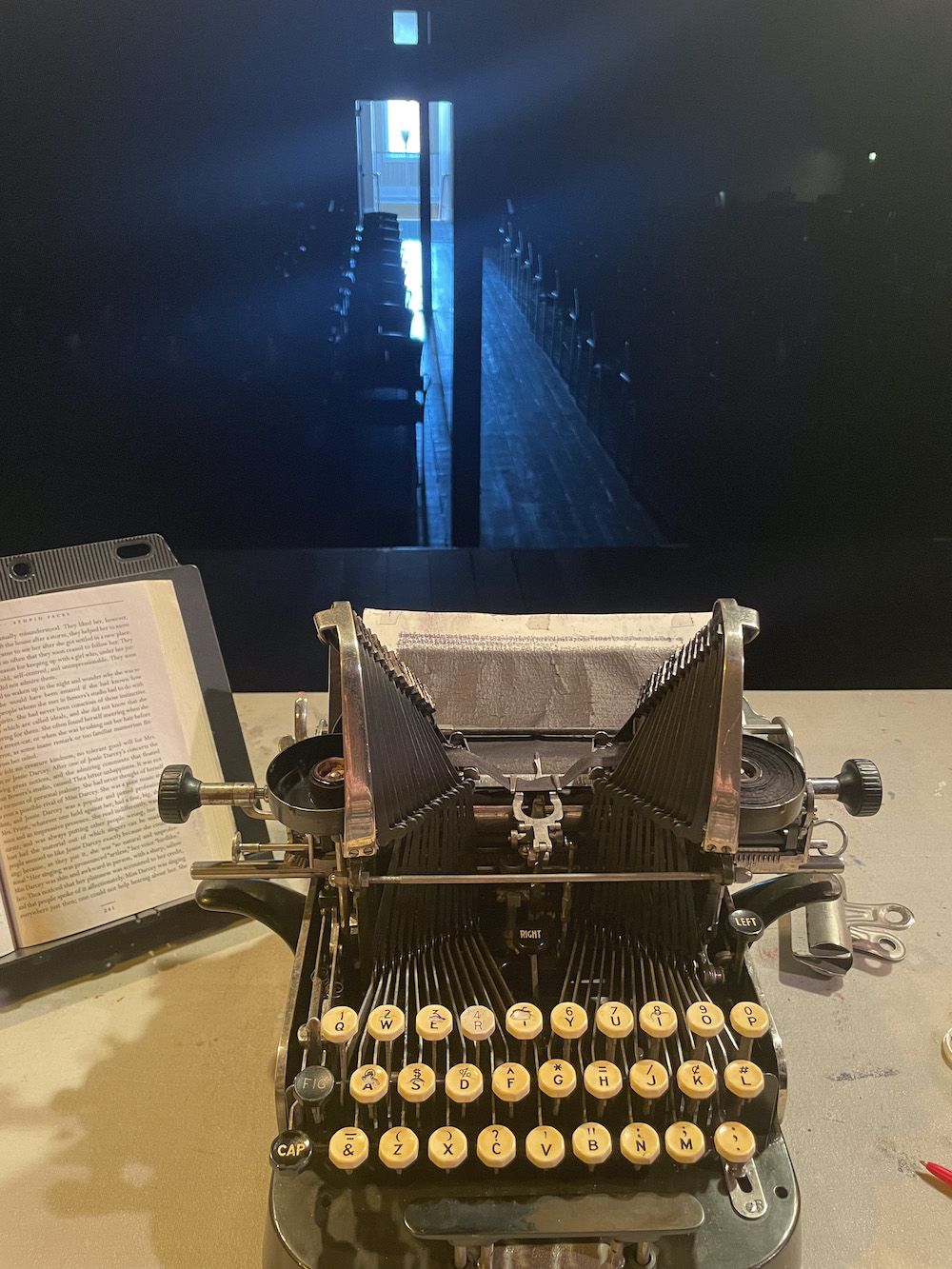

As I approached Cather’s childhood home, I could hear a distant tap-tap-tap, bing! Tap-tap-tap, bing! Birds were singing joyously—could they be larks? I sat down on the soft green grass in the front yard and watched Youd typing on the porch; the typewriter was ancient, an Oliver No. 3 with “wings” from 1898. Youd, 55, was dressed casually in a long-sleeved T-shirt and jeans. He has an impressive head of thick white hair, accented by his Clark Kent black-rimmed glasses. Youd was deeply absorbed. If he heard me coming, he didn’t show it. It was quiet, even with the tapping and chirping. The rhythm of the typing was hypnotic as I took in the surroundings and thought about Willa Cather and one of her main semi-autobiographical characters, Thea, who saw things differently but didn’t yet realize that she was an artist.

Later that day, I had the opportunity to enter the Cather house, which was included in a “town tour” the Cather center offers. Walking through each room felt like I was reading one of her novels in 3D. I climbed the narrow wooden steps to the attic, where Cather’s bedroom sprang to life: the tattered, faded, rose-patterned wallpaper, the floor-to-ceiling window, the bed where she brought hot bricks to place under the covers for warmth. Cather’s vivid description of her attic bedroom was eerie in its precision. My whole trip to Nebraska was beginning to seem surreal.

Typewriter Youd used for Cather novels: Oliver No. 3 with “wings” from 1898.

No Fear or Loathing

One day back in 2012, Youd was sitting in his studio when he came up with the idea of retyping novels as an art project. He had just closed the book he was reading and started squeezing and pushing on it—he wanted to crush the book so he could “get all the words onto one page,” he tells me, pressing his hands together. The book became an object with a formal quality. There’s “a black rectangle inside of a white rectangle,” Youd says, referring to the text within the encompassing margin being the white rectangle. “I wanted the texture of the words, the weight of the words.” It had to be a typewriter because the book is typeset, he reasons. “It’s a font, and I want to echo that.”

Alone in his studio, he proceeded to retype Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, on an IBM Selectric—the same model Hunter S. Thompson used. Youd recalls feeling “happy, relatively speaking.” He was excited, thinking, “Wow, this is kind of a successful experiment, I want to do another.” So, he typed a few more novels in his studio, and it became clear to him then that the project should take the form of a literary pilgrimage. “It should be a public thing, where I go to a significant place in the author’s life or the setting of the book I’m retyping,” he recalls.

Mat Gleason of Coagula Curatorial gallery in Chinatown—where I first saw Youd typing—was showing Youd’s visual work and was a big proponent of this new project. He took Youd to art fairs in Miami and New York, and that’s when Youd’s career really took off, outside of LA. It was his retyping of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in Brooklyn that caught the attention of Cristin Tierney gallery.

Youd liked how things were going, but he knew that the pilgrimages would have to end at some point. That’s when he was struck with the idea of a list.

“Everyone has a list of something. I’m gonna type 100 best novels,” he remembers enthusiastically.

“I’m ambitious by nature,” he says matter-of-factly. “I like something big to tackle. And that felt pretty big!” Youd also liked the whole literary pilgrimage aspect of it all: “It’s whimsical. Almost a pop-culture thing that we do. We make journeys. We go to Graceland. We make pilgrimages. That’s the kind of people we are.” Who could argue? Besides, he notes, “It’s catchy. One hundred novels. I’m not just a guy going around the world typing novels. I’m typing 100 novels! People love numbers.”

The Country Tour

The next day I was scheduled to go on the “country tour,” where Youd would be typing. It was another stunning day on the Great Plains as my tour guide drove us over the bumpy dirt roads in her SUV. We visited several tiny cemeteries and Willa Cather’s farmhouse—or rather what was left of it: a bit of foundation and a water pump. The countryside was lush with wildflowers, purple prairie clover, bunchgrasses, mulberry bushes and tall scraggly cottonwood trees, all described so tenderly in Cather’s novels. I was seeing the author’s words come to life and beginning to understand the gravity of Youd’s pilgrimages.

Youd typing at the Pavelka Farmstead, photo by Tulsa Kinney

We arrived at our last stop, the Pavelka Farmstead, a historic house which was being renovated to host visiting scholars and interns. Youd was set up outside in front, typing intently. We interrupted him to see how it was going. He was nearing the end of the book—only 20 or so pages to go. The paper he was typing on was tattered and saturated with black ink, thin tears revealing the page underneath. Youd was excited to show us the diptych and pulled the two pages out of the typewriter. (It should be noted the novels are retyped over and over onto a top page, with a second page underneath. The top sheet naturally gets saturated with ink, often tearing through to the page underneath. They are displayed side-by-side as a diptych after each novel is finished.)

A Better Reader

When I asked Youd to describe his “reading” process, he readily answered my question: “Anything I’m typing, I’ve read before. So, there’s not going to be many surprises in the plots.” With his close reading of each word and sentence, “it’s a significantly heightened experience of reading versus when I read it the first time.” He’s also reading during the daytime, when he is most alert and receptive (not lying down!). “I’m devoting my whole day, the best I can give it.” This made me feel envious, and even a little guilty, as I usually reserve my reading for the end of the day, when I can barely finish a chapter before I start dozing off.

Is Youd’s project about optimizing his own personal reading experience? Isn’t that self-serving, selfish and self-indulgent (adjectives often associated with artists)? Does he have naysayers, people that are skeptical, or even jealous of him, like me? Youd admits that his art might not appeal to everyone. “People have come up to me and told me what I’m doing is stupid.” Once at a performance in a museum a woman was circling him. “I could hear her breathing and sighing,” Youd recalls, with a wry smile. “She was pissed off. She just hated what I was doing.” She left with a comment in the guest book: “The 100 Novels Project is singular in its uselessness.”

Elizabeth Bishop’s The Complete Poems, 1927 – 1979, 2018, courtesy Cristin Tierney.

On The Prairie

It was my last day in Red Cloud, and Youd would be finishing retyping The Song of the Lark on the actual prairie. This time I followed my tour guide on “The Prairie Tour,” a five-mile drive outside the town. When we turned off the main highway it was as if we entered a Prairie Land movie in vivid Technicolor. (Were the homemade Swedish pastries I had that morning laced with LSD?) The prairie lay before us with tall wheat-yellow grass pressed against a blue sky dappled with white fluffy clouds. It was a majestic sight to behold. My guide informed us that these prairie lands are part of the Cather Foundation preservation program, of which they own over 600 acres. The goal is to return the land to its 19th-century conditions—before agriculture and foreign plant species despoiled the countryside. A noble deed that Willa Cather would highly approve of.

Finished diptych of The Song of the Lark retyped on the Prairie, photo by Tracy Tucker.

Youd had been in Red Cloud for 18 days and retyped 430 pages of The Song of the Lark (her longest novel). He made several attempts to set up in the prairie land, but until now inclement weather conditions had stymied his plan. Today the weather was ideal, with a light warm breeze—a perfect day to conclude the project. Youd was already there when we arrived, with his table, book and typewriter set up in the tall grasses—and only 15 pages left to type. We didn’t linger to watch Youd perform. It seemed he should be alone for the occasion; he didn’t object to our leaving either.

After Youd finished his retyping of the novel, we ended our Red Cloud days at the local bar and grill, as I’d heard they make a great burger. I asked Youd if he was sad about ending his 72nd novel and leaving Red Cloud. “There is a melancholy aspect to literature in general,” he replied. “It’s about the passing of time. Time passes, and when enough time passes, [whether it be] the end of life, the end of a chapter of one’s life, or a relationship, there’s always a sense of sadness in the story.”

Youd didn’t have that much time to indulge the blues though. The next day he would be packing up and moving onto Omaha and retype Cather’s My Antonia at the Joslyn Art Museum (co-sponsors of the project), bringing The Prairie Trilogy to a closing. “I have a jumble of emotions on completing a novel. Especially completing a project in a location that is as close to perfect as it really can get,” he said, referring to the generous hospitality the Cather center provided. “To be out here, to be in the historic buildings, on the prairie that Cather knew as a child that she captures for us so vividly.”

Being on the prairie clinched it for me too. It really made Willa Cather’s stories come full circle. Was this the lesson I could take back with me? Art is supposed to open one’s eyes to new ways of seeing. Did Youd’s performances do the same for new ways of reading?

“I didn’t necessarily know, when I typed that first [novel], how it dawned on me that what I was trying to be was a good reader,” Youd muses. “Because that’s what the project is. It’s about trying to become a better reader each time you sit down, and measurably be in a different spot as a creative thinker, as a critical reader.”

Sadly, many people don’t read books at all anymore. What

often passes for reading these days is the content on social media. It’s been reported that younger folks spend around nine hours a day in front of a screen. Imagine what a difference it would make to that person’s life if they devoted even a few of those hours to reading a book.

I know Tim Youd can imagine the difference; he’s made it his life’s work to do so. Let’s all take a lesson from Youd, and prioritize reading a book—in the middle of the day!