For an artist who has deliberately cultivated a naïve style, Umar Rashid (who also occasionally calls himself Frohawk Two Feathers) appears to have calculated the exhibition’s title, “Per Capita” with almost labyrinthine deliberation—an amalgam of the coyly matter-of-fact, ceremonious and slyly deceptive. Alternate readings might suggest for the head as much as the more commonplace, by the head.

An impressive, blue painted ceremonial arch, titled 8th Wonder: Portal to Los Angeles Past, Present and Future (2021), greeted visitors to the gallery; yet the transfer prints that covered the structure—white cougar and bird-like silhouettes collectively titled, “All Power to the Women” (2017)—seemed slightly disconnected from both the triumphal aspect of the arch and the “Per Capita” drawings hanging at the rear of the gallery. But disconnection and detour seemed to be subsidiary themes of the show. Ostensibly the centerpiece of the show, the eponymous “Per Capita” pieces (2021)—one an acrylic-on-cowhide with rampaging toy-like horses and masked soldiers slashing at each others’ heads; the other, a suite of 12 acrylic-on-paper drawings (of women’s faces—subtitled “Hortense through Candy,” each captioned “PER CAPITA”)—could not by themselves encapsulate either the artist’s stylistic range or the exhibition’s scope which, in addition to serving as a mini-retrospective of the artist’s work (from 2013), amounted to an exorcism of colonialism past and present.

Rashid achieves his exorcism not merely through stylistic means (though he is a practiced hand at this, borrowing from Japanese graphic work of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Indian and Persian miniatures, Native American art dating from various periods of US colonial expansion, and Anglo-American folk art from the same period), but by revisiting—and aggressively messing with—the usual historical narratives. One example of this is a 2017 suite of unique zero graphic transfer prints (with ink and acrylic) on birch panels: an 18th-century “Shock Doctrine” scenography of colonial invasion, occupation, suppression and revolt. Women are depicted in full contention with their male counterparts, ready to take on leadership roles.

Umar Rashid, Enjoying Bison, 2019. Courtesy Transformative Arts.

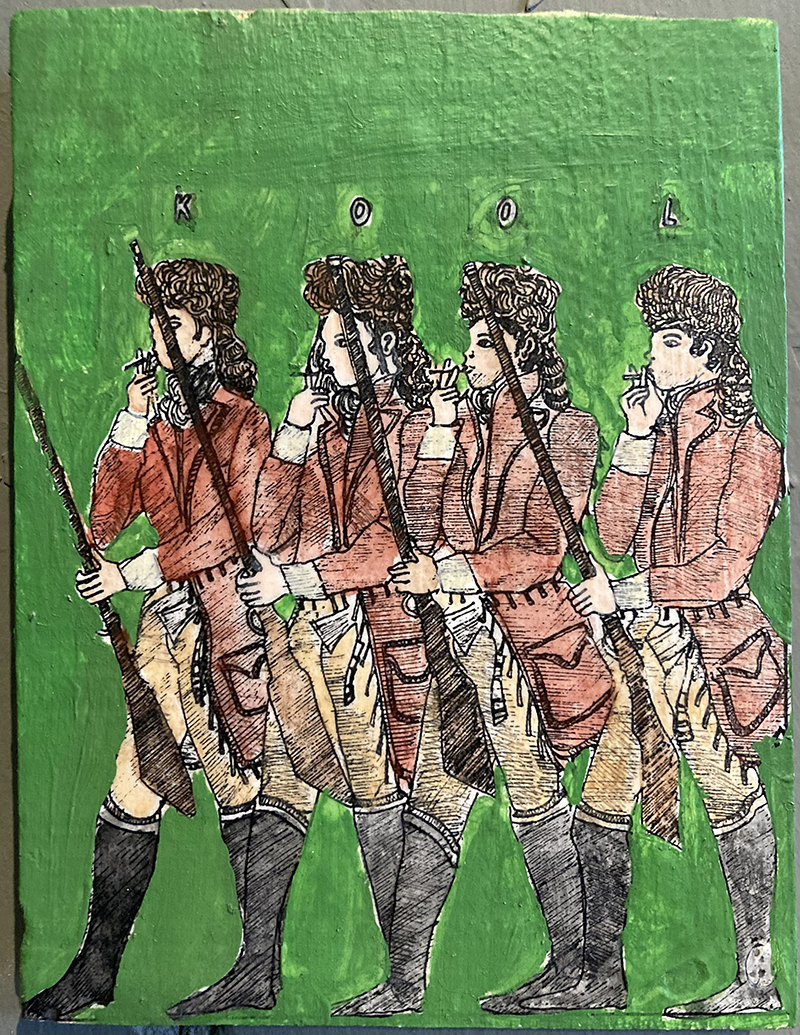

Rashid has continued developing these interventions by historical reinvention, composing (in 2019) what is effectively a graphic mytho-satirical epic of colonialism in 40 panels (including a frontispiece), Views of Colonial Fabric Softener or, The Sidney and St. Marc Expedition to the Pacific, 1795. (e.g., panel 8, “Trappers/Sharpshooters or historical origin of Kool cigarettes”). It was perplexing that this ambitious series was not featured more prominently, but the gallery’s spatial limitations clearly impeded the show’s organization and installation. That said, not all of the work exhibited served Rashid’s overarching themes. Not to dismiss the totemic aspects of Rashid’s mythographic exorcism, but the “Yves Klein” garden totems could have easily been culled from the show.

In addition to a surprisingly authentic-looking drum, Rebel (2013), Rashid showed an embroidered and appliquéd cape, Trickster (2019) bearing such insignia as a snake curling around an octagonal spider’s web (with Afro combs taking the place of classical Greek key and scroll-work for the decorative trim). Rashid also plays a trickster here, which is half the point. If colonialism’s legacies are still with us (on a “per capita” basis or otherwise), we continue to re-enact their ceremonies and traumas, even as we lampoon and subvert them.