Mining tensions between the hyper-feminine and the fragile masculine, Troy Montes Michie continues his interventionist textile and collage practice with a body of work centered on the reappropriation of the Chicano countercultural figure La Pachuca. Dishwater Holds No Images, his second solo show at Company Gallery, investigates the commodification of the zoot suit, a once-radical fashion statement adopted in the 1940s by bicultural immigrants that resonated well beyond the wartime period.

Montes Michie employs the image of the zoot suit as a sartorial manifestation of marginalized communities’ desires to conform to America’s white middle class. His space-consuming work presents parallels between the acts of tailoring in fashion and collaging in art. Whether on bodies or on canvasses, both practices are defined by aesthetic interventions that express racial, gender or cultural identities. The collaged textile elements in Montes Michie’s canvas works are held together by paint and needlework and point to his efforts to create new meaning from a fragmented assortment of relics.

Beautifully expressing the intersection of tailoring and collaging in Was the Beautiful Woman in the Mirror of the Water You or Me? (2022), the artist’s 40-foot-long patchwork comprises garment bags, wire hangers, catalog pages, clothing scraps, belts, and zippers hand-stitched together. Hung Out To Dry, his 2021 sculpture series of resin-treated garments hung on steel drying racks is also interspersed throughout the gallery, culminating in Amanecer o Atardecer (all other works 2022) which features monochromatic shirt sculptures hanging overhead on crisscrossing wires.

Troy Montes Michie, Installation view, 2022. Courtesy Company Gallery.

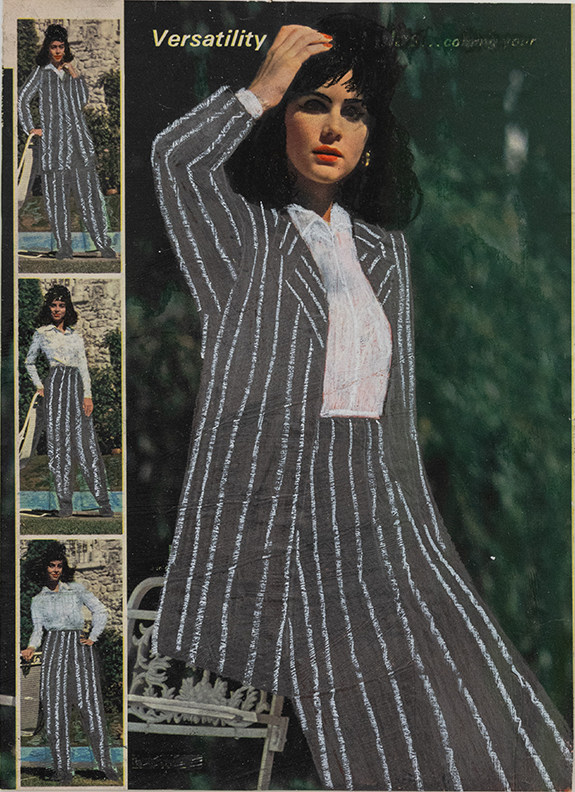

The subversive quality of zoot suits is rooted in their blatant betrayal of gender norms, a fact to which Montes Michie fittingly pays homage. Most depictions of “Latinx” women are manipulated images of white models from 1970s magazine ads—their skin tone and lipsticks have been darkened, their formidable pinstriped suits and coiffed hair rendered in paint and graphite. The aptly titled Versatility, measuring 11 x 8 inches, perfectly captures the gender rebellion of the zoot suit with snapshots of a model whose drawn-on pantsuit becomes the basis for a visual pattern that Montes Michie liberally inserts into new contexts throughout the series.

Beyond provoking fear of female sexuality, the works also point to the destabilization of traditional class structures that the Pachucos represented. To see women of color donning the uniform of white men and flaunting their affluence in the face of the white majority implied the permeability of class categories and consequently stirred significant public anxiety. By projecting the politically wrought zoot suit, which functions as both costume and symbol, onto white female subjects, Montes Michie tactically inverts longstanding notions of beauty and femininity, and of what it means to look and feel American.

His tangible portrayal of the interrelationship between consumer materiality and cultural identity is not only incisive, but also unforgettable. In Montes Michie’s idealized version of the middle-class American Dream, women of color are, at long last, approaching the fore of the narrative. Yet his demonstration of how far we have come reveals how much more work is yet to be done.

0 Comments