They say how a person does one thing is how they do everything, and the most recent edition of the Hammer Museum’s biennial, “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living” (its sixth), put the axiom into practice. Curators Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez, along with Luce Curatorial Fellow Ashton Cooper, proceeded from the intriguing perspective of selecting artists whose work deal in some essential way with the fabric of everyday life, both on an intimate, individual scale and with a broader, rhizomatic sense of culture as community. There were multiple examples of very fine contemporary painting, updates to vernacular genres of portrait and landscape that give the international scope of divergent life experiences and public society their due. But at its most memorable, “Acts of Living” featured a trove of narratively engaging, materially adventurous, immersive-curious, genuinely surprising and original displays.

Often unapologetically Instagrammable, yet at other times treading into more esoteric, anti-aesthetic territory, the biennial featured many artists who achieved compelling balances between thoughtfulness and spectacle, confession and theater, emotion and art history. There was also a notable presence of gigantic (and in other ways maximalist) painting, and striking textile work, along with a prevalence of sculpture made from as many different, unconventional materials as possible and in some cases by a plurality of collaborators—offering welcome dynamism, evidence of the human hand and little mysteries to solve, on an impressive scale that traditionally signals a classic institutional biennial.

Guadalupe Rosales. Installation view, Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2023. Photo: Charles White.

If you only saw one piece from the show on Instagram, it was probably Ishi Glinsky’s Inertia—Warn the Animals (2023), the 11-foot-tall mosaic Scream mask whose cloak morphed into a wrap-around altarpiece or reliquary, displaying many varieties of cultural symbolism and personal artifact. “Mixed media” is a vastly insufficient term for its universe of hand-wrought items of canvas, resin, wood, foam, pigment, ink, industrial adhesives, steel, aluminum, fiberglass, goatskin rawhide and deerskin rawhide, among other unusual materials. In Glinsky’s approach, the fusion of borrowed Pop iconography and Indigenous ceremonial craft-based objects (often made by otherNative-American artists and designers) represents a strange kind of liminal cultural context, as well as a subversive reversal of the usual extractive cultural appropriation.

Another collaborative work was the festooned architectural vessel by artist Tanya Aguiñiga and the AMBOS collective cross-border project was an accrual of tactile testimonials to existence and hope. By using the historical concept of the quipu—talismanic handcrafted memory records—as an active bulwark against cultural erasure, this particular piece and the project in general give monumental form to the energy of an engaged community. Its physical form enacts this further, as its heft and maximalist surface resolves on closer viewing into increasingly singular and individual objects/gestures—hands reaching backward and forward through the spaces of history.

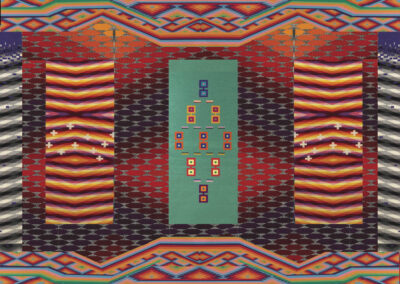

Guadalupe Rosales’ practice is also concerned with record-keeping at the intersection of the personal and the collective—crowdsourcing primary documentation online and transforming this citizen archive into accumulative environments of amped-up color, pattern and aesthetic theatricality. Her work for the biennial was like a dance club at the end, or perhaps the dawn, of history. If some artists seek to describe or embody a sense of oneness between daily existence, art-making and the world, Dominique Moody lives it. She pursues her peripatetic, performative and site-responsive assemblage practice from the platform of her mobile live/work studio, N.O.M.A.D., which she graciously parked at the museum and opened to visitors several times during the run of the biennial.

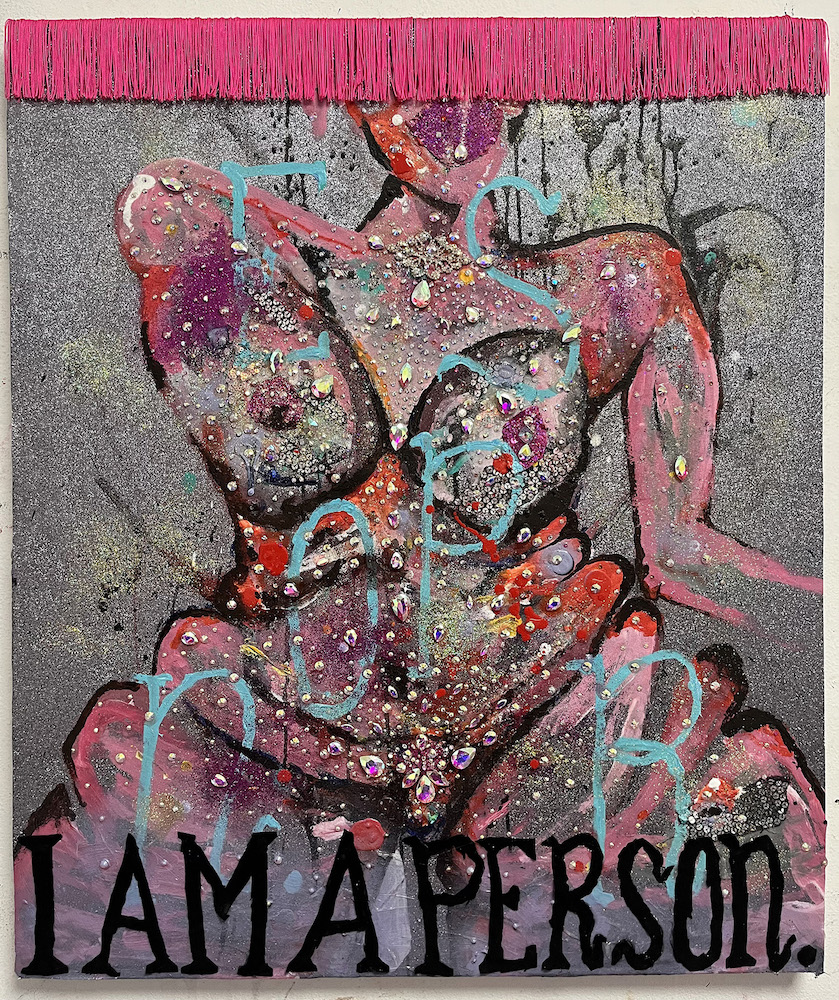

Page Person, The Glittering World, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist and The Hammer Museum.

In a way Page Person’s riotous celebration of color and texture also represents the fusion of life and art. Grounded in her own evolving sense of self and confidence, riffing on her intertwined interest in drag persona/performance and painting, Person’s conflation and cross-pollination of costume and canvas calls to mind iconic art-historical antecedents such as Rauschenberg’s 1955 proto-combine Bed, in its

doubling of biographical record and body-embracing materials. Melissa Cody makes weavings in much the same way—referencing historical textile work of the Navajo people, as well as the scale of royal tapestry and the syncopation of hard-edge abstraction.

Esteban Ramón Pérez is also in a conversation with modern abstraction on an institutional scale, but it’s AbEx and he uses leather. The evocative, gestural line-drawing enacted by ribbed seams, eyes set in motion across subtle variations in tone and surface, and the warmth of the expansive scale provoke germane reconsiderations of their own. Likewise, the materially assertive and history-weighted Mesoamerican-infused ceramics by Luis Bermudez, and the radiant, regal and soulful earth-magic of the politically fearless, ancestrally propelled ceramic vessels and plaques by Akinsanya Kambon, provided remarkable examples of work that are indelibly present as themselves, while containing multitudes of meaning in their folds. This kind of suffusion of technique with the artist’s hand, materials of craft, energized legacy and modern conscience are emblematic of the biennial’s investigation of how artists live today.

-

Page Person, "Trans Icon Nail Set," 2023. Courtesy of the Artist and The Hammer Museum.

-

Dominique Moody, "N.O.M.A.D.," 2015-2023. Photo: Khari Scott. Courtesy of the Artist and The Hammer Museum.

-

Melissa Cody, "Dopamine Dream," 2023. Courtesy of the Artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.