Rooting through used bookstores in Berlin in 2006, I discovered the minibuchs published in East Germany during the ’70s and ’80s. These tiny volumes, with their exquisite bindings and photos of happy children giving floral bouquets to returning cosmonauts, launched me into collecting miniature books. Over time I narrowed my focus to handmade books, books by artists and books that played with the idea of what a book could be.

The world of miniature book publishing draws artists who recognize an opportunity to explore the book’s possibilities as an object and conveyer of what a book might mean. With full-size books, the costs of production constrain creativity and unusual solutions. But presses like REM Miniatures and Juniper Von Phitzer, along with individual artists such as Alexis Smith, Nancy Jackson and Candice Lin, have exploited the freedom afforded by small scale and low production overhead to create wildly imaginative miniature books that capture and beguile us with the emotional magic felt when we first began handling and reading books. Recently this was explored in “TOMES,” a 2019 show devoted to artists’ books of all sizes, at the Williamson Gallery at ArtCenter College in Pasadena. In the same year, the possibilities for extended creative explorations afforded by the miniature was seen in “Dreamhouse Vs. Punk House!,” the invitational group show staged by Kristen Calabrese and Josh Aster in three astonishing dollhouses filled with a compendium of artwork across all disciplines.

Given the heightened interest in this form and my own collecting, it was only a matter of time before I discovered Pat Sweet and her publishing enterprise, Bo Press, operating out of Riverside, California.

Born in Brattleboro, Vermont, and growing up in Keyser, West Virginia, Sweet studied at Potomac State College and West Virginia University before earning her MFA in stage design from Southern Methodist University. Joining the theater department at the University of California Riverside in the ’90s, she honed her skills at devising inventive solutions to individual problems (e.g. creating a coat that could be removed, turned inside out, upside down and backwards to become a suit of armor).

The Windhover, by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Bo Press, 2017. 2 ¾ x 1 ¾ in.

The genesis of her oeuvre dawned in a dollhouse she built featuring an extravagant library, complete with spiral staircase (“The hardest thing I’ve ever made, bar none.”). Setting to work creating miniature books to fill the Lilliputian shelves, she found herself caught up in the excitement of creating not just tiny blank volumes but finished books that she would actually want to take down and read. Eventually she started the Bo Press website in 2007 (named for a beloved dog), and began making her books available to collectors, who have kept her busy ever since.

Sweet has pursued a highly idiosyncratic program, publishing not what she thought might sell but what interests her. However, this hardly indicates a parochial restriction of topics. In the first year alone, the content of books published by Bo Press included texts by John Webster, Shakespeare and Thackeray, as well as books on fans and corsets, geometry, beetle species, a listing of sightings of flying carpets, the imaginary Latin used by printers and a re-creation of the map used by the Bellman in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark. The consistent interest in creating portfolios of maps is a touchstone unique to Bo Press. Over the years, Sweet has published map portfolios that detail Napoleon’s retreat, the Nile, the Silk Road, the various kingdoms of Gulliver’s travels, the fictional town in Trollope’s Barsetshire, the map used by Phineas Fogg, and the imaginary world of Eirie, among others. This highly particular path goes a long way toward explaining why the publications of Bo Press display such variety and wit and avoid the uniformity of other press’ efforts.

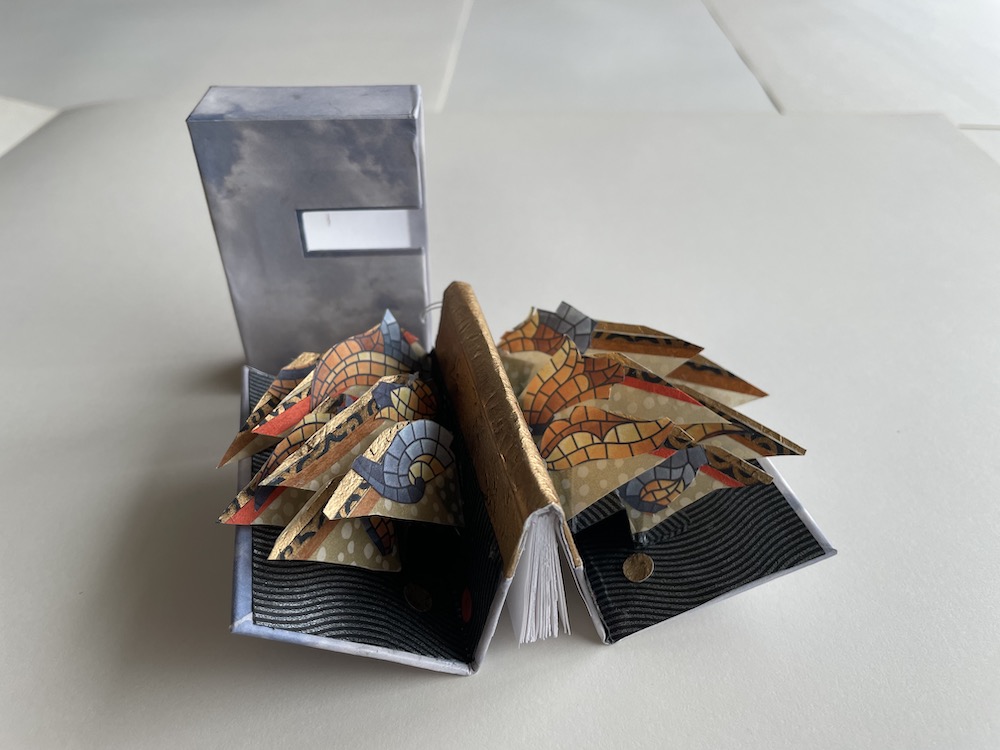

Sweet quotes Archibald MacLeish: “A poem should embody what it indicates.” Thus, when opened, This is Not a Book reveals a smaller book nestled inside, a volume containing mock-ups of the covers of fictional books that only exist as references in novels. (The Argentinian writer, Jorge Luis Borges, would have loved it.) The Windhover (2017) explores how a book’s construction moves meaning into the poetic realm. Based on a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins about a falcon, The Windhover physically opens in two directions. Opened as a traditional book, the poem is disclosed along with images of wings and feathers. But when opened from the other side, an abstract architecture unfolds and extends itself, like wings expanding out of the book’s binding.

Oscar Wilde’s reply when asked the meaning of one of his fairy tales was: “I did not start with an idea and clothe it in form, but began with a form and strove to make it beautiful enough to have many secrets, and many answers.” Sweet’s books contain secrets, marvels, enthusiasms, questions and wonders—all qualities we thirst for as we navigate the strange times in which we find ourselves.

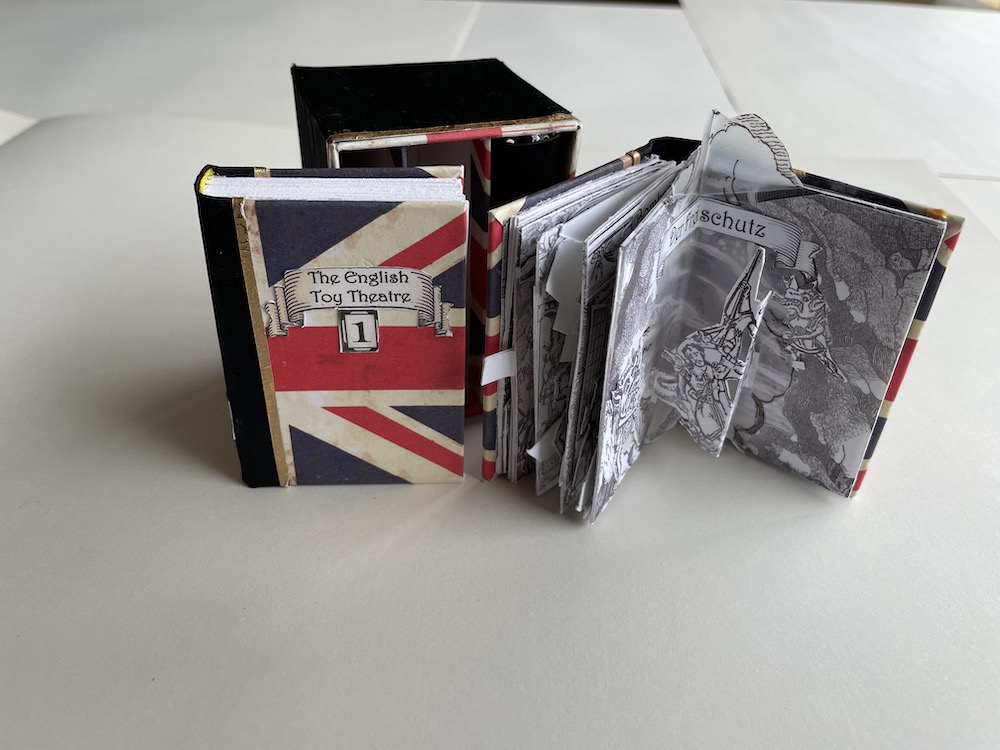

N.B.—In full disclosure, I have written the texts and painted original illustrations for one of Pat’s recent spectacles, a three-volume history of the English Toy Theatre, with a volume of pop-up scenes from the 19th-century English stage, and a complete theater with pantomime in progress, which unfolds out of a portfolio. (Look for my cat, Nino, and a portrait of my late husband, Robert Baruch, in the stage proscenium.)

For more info: https://www.bopressminiaturebooks.com/