The downtown art scene in New York City has a long and illustrious history that can hardly be contained in any one exhibition. Yet the New Museum’s “Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery 1969–1989” makes it possible to say a great many things. Organized by Ethan Swan, “Come Closer” is about the many individual forms of expression that included the active and sometimes volatile downtown New York scene of the ’70s and ’80s. It is also about the individuals who made these statements, about the timbre of their shared existence, and how we may celebrate the real and mythical proximity between them.

The exhibition actually emerged out of a more extensive project called the “Bowery Artist Tribute” which so far has comprised three printed publications, a film, and an interactive website from which anyone can travel along the length of the Bowery, starting at Canal Street and ending at the corner of 4th Avenue and 10th Street, clicking along the way links to read histories of who lived there. Out of all these inhabitants, Swan selected the work of 15 artists: Barbara Ess, Coleen Fitzgibbon, Keith Haring, John Holmstrom, Curt Hoppe, Colette Lumiere, Marc H. Miller, Adrian Piper, Adam Purple, Dee Dee Ramone, Joey Ramone, Marcia Resnick, Bettie Ringma, Christy Rupp, Arleen Schloss, Charles Simonds, Eve Sonneman, Billy Sullivan, Paul Tschinkel, Anton van Dalen, Arturo Vega, Robin Winters, and Martin Wong.

Entering the gallery one is faced with a variety of documents, ephemera, and only a few actual art works. Directly across from the elevator is Study for La Vida (1984) by Martin Wong, whose retrospective graced the reopening of the Broadway location of the museum itself after an extended remodeling in 1998. This single painting presents us with a close-up view of working class families in every window of a red brick tenement building, framed by curved window apertures lacking panes and the enclosure of the fire escape. The unadorned surface of the building is knobby and mottled, like skin, and Wong uses it as both a backdrop and a framing device, making a portrait of enforced solitude out of a portrayal of the social tension among neighbors in the same building. This is one concept of urban existence: what should be a home exists more like barracks or a jail cell. It only holds lives, but does not encourage them.

In direct contrast is Adrian Piper’s conceptual piece “Hypotheosis: Situation #11” in which the artist takes photographs of her studio/home, in particular of the time she sat in to make her work, and the photographs are then included in a graph which connects the real objects to their role in the greater domestic space. She goes into detail with descriptions such as: “…the series of photographs documenting my own spatiotemporal passage through a situation, the accompanying short essay that explains the underlying philosophy of this work. Specific to each work is the actual situation or context I am registering: meditating, eating breakfast, reading the New York Review of Books, walking around a chair or through my loft, taking a walk outside…” In this way the artist attaches a maniacal degree of theorizing to every conscious action that makes up the structure of her day. We know she has a life, one that registers specifically in artistic terms, because the document of the artwork itself not only acts as evidence, but it also lays the groundwork for future days and moments to be revealed in a likewise fashion. It combines two types of communication: the intimate and the systematic. Piper wants to describe her life to us, alternating between the use of words and of direct connections planned out to show an archaeology of utility and its direct correlation to creative discovery. This is how the artist deals with the banality of existence.

Another conceptual work, also connected to the banal and the commonplace, but depicted on video, therefore dynamic and causal instead of theoretical and esoteric, is Paul Tschinkel’s Hannah’s Haircut (1975). The feminist artist Hannah Wilke is filmed topless giving Claes Oldenburg a haircut. The camera pans in close to Oldenburg’s face, with Wilke’s arms wrapped around him, her own dark tresses framing his giddy face and his half balding pate. Wilke is naked except for a pair of long black pants that match her hair, and her every gesture—though she is performing a duty traditionally reserved for men—evokes the desire men have for beautiful women while they themselves are in the middle of “beautifying” themselves. Wilke is in control here but she is never a threat to Oldenburg; she attends to him with due care, and is at moments even solicitous and affectionate. There are many symbolic levels within this film that may speak to a communication between the artistic practice of men versus women, of the stature of the male subject and his female interlocutor or opponent, or it may also be seen as a merging of different creative entities. We must remember that in the early 1960s, a generation before this, Oldenburg was not known for monumental soft sculptures or public commissioned artwork, but was in fact one of the progenitors of the Happening, a radical anti-theater which matched camp dullness and established a bellwether for new artistic practice. Oldenburg moons at the camera sheepishly and Wilke alternates between vamping it up and holding his head as if it were a big lollipop. Everyone who saw it probably wished they could get a haircut from Hannah…

Other artworks from “Come Closer” point to how artists were harvesting the abandoned territories of the downtown area. Adam Purple was a tall, shy hippie-type who wore all purple clothing, and rode around on a purple bike handing out purple pamphlets. He created his own version of eminent domain as Zen garden in “The Garden of Eden” (1975–86) made in concentric circles, including 45 fruit and nut trees, and growing to 15,000 square feet before being bulldozed by the city. Keith Haring was experimenting in sampling the modes of creative expression from abstraction as collage to his iconographic tagging that turned into paintings in subways, construction sheds, and on his very own apartment’s front door, which sits in the middle of the gallery.

Marc H. Miller, “Harry Mason, Harry’s Bar, 98 Bowery, c. 1974,” “Harold & I Are Waiting For 8 a.m. Ready To Open Up For Business.”, courtesy the New Museum, New York

Marc H. Miller’s “Harry Mason, Harry’s Bar, 98 Bowery, c. 1974,” a series of Polaroid photographs with short, deadpan statements about their subject, a local bar owner whose personal history, and working class dress, paints him as a denizen of the pre-scene Bowery. Obviously he was a much-loved character, and Miller epitomizes him in every shot. From the way that Miller is posed in the first shot, it seems that he either worked at the bar, or was posing as a bar-back to insinuate himself into this rather matter of his down-at-the-heels art project. The titles are written onto the snapshots in the handwriting of their subject, as he matter-of-factly recounts the activities of a regular day: “Harold & I Are Waiting For 8 a.m. Ready To Open Up For Business.” “I Am Wiping The Bar.” “I Am Serving A Glass Of Beer To One Of My Customers.” Miller picked a very Clark Kent figure to mythicize a working guy, who does his job, loves his cat and takes naps sitting up. He is an old fashioned Bowery boy, like a character in a novel. Miller is adding to the quality of art practice while also creating oral history.

Some of the documents on display here are meant to give a feel for the experimental and DIY communal culture of the era and its varied milieu, including visual arts, poetry, punk rock, club culture, artists at salons and happenings in heir own spaces, getting ready to go out or arguing over artistic agendas, or merely standing inside looking out into the night. A series of slides taken by Billy Sullivan, “250 to 105 Bowery” (1978-89) attest to the social fabric of the time. There is also a collection by Alan Moore of “Ephemera from MWF Video Club” with assorted VHS tapes, newsletters, announcements, T-Shirts silkscreened by Arturo Vega, and a poster by Anton Van Dalen which shows a skeleton with two skulls, each head with the words “Heroin” and “Real Estate” and in large red capitals above: “THE TWO-HEADED MONSTER DESTROYS COMMUNITY.”

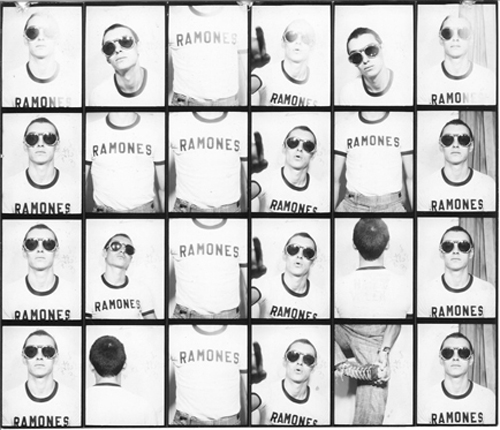

As a historical exhibition, “Come Closer” depends heavily upon the collection of the New Museum, especially in its use of marginal and ephemeral materials that actually look like they were taken out of an archive; and since the exhibition is housed on the educational area, it does not have a lot of floor or wall space to play with. In the place of Haring’s door, it would have been more interesting to see some of his early subway drawings, or at least one of the gallery-intended paintings he made later on. There are some elements of the exhibition that are charming, while other are merely cloying, such as Bettie Ringma’s group portrait of herself and The Ramones, or half-assed sketches by one of the band members, showing domestic scenes in which domesticity and parental authority are devoid. Self-portraiture as solipsistic narrative in a bunch of grimy black-and-white photographs does not stand up to the rigor or inventiveness of other works in the exhibition; down a hallway lit only by glaring fluorescent bulbs are screen prints of concert posters and graffiti on bare white opposing walls, giving a ghostly echo to the throwaway medium of public walls in the streets. We are left with a cumulative echo, and in listening to its refrain, only then do we come closer to what was gritty and magical about life around The Bowery.