In her Culver City studio on a late summer afternoon, encaustic painter, printmaker and educator Pamela Smith Hudson revealed the origins of her vocation as a “materials artist” dedicated to exploring the potentials of paint, clay, print and wax: “My dad was a cement mason,” she said, while surrounded by her liquid-looking charcoal, teal, rose and cream-white canvases. “Dad worked on the federal building,” she emphasized. “So cement, plaster and wood were always around the house. Also, my mom was an artist, or had been.”

With a landscape-oriented show that stretched from early spring through the waning days of summer at the California African American Museum (the exquisitely curated Charting the Terrain, which also featured works by Eric Mack), and a swiftly mounting reputation for taking encaustic painting to new heights, Hudson has become a new luminary on the Los Angeles arts circuit. For most of her adult life, though, she has produced work quietly in her studio when able to find the time. Until recently, she juggled painting, raising her children with her husband, working as an arts supplies representative for major companies, and teaching at Otis College of Art and Design and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

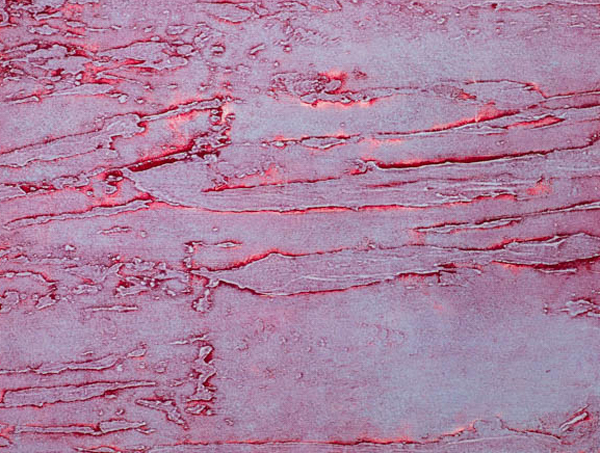

City of Angels I, (2017). Monotype on clay panel (1 of 8). 9 x 22 inches

But three years ago, Hudson’s mother grew ill and Hudson realized that she wanted to bring her art out into the world.

“My mom stopped painting to take care of the children, and I never knew she was a painter until we went to a Lee Krasner [show]. We were looking at the paintings, and she told me that she had been an artist. Later, after she got sick, there was a connection between her being in hospice and making this journey of leaving her body that made it okay [for me to focus more on my art]. I realized I had been of service to my family—family’s first—but I decided to have an exhibiting career.”

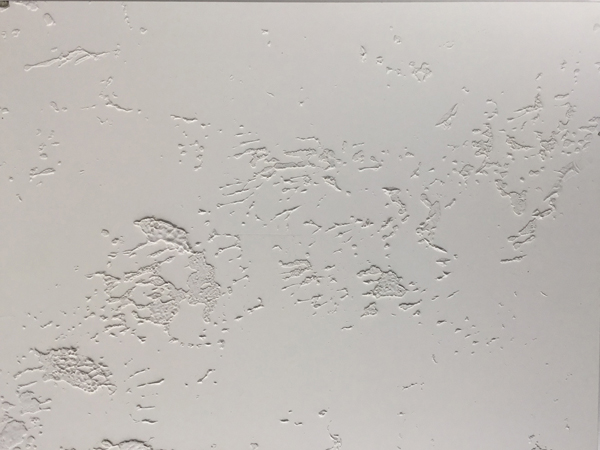

Ever, Never After (2016-17). Cold wax mixed media on canvas. 48 x 72 inches.

While Hudson only began showing in earnest in 2015, she has worked in encaustic since the 1990s: That’s when she met Daniel Freeman, the printer at the Gemini G.E.L. print shop and publishing house. Freeman noted a resemblance between Hudson’s practice and that of Jasper Johns, with whom he had collaborated. Freeman encouraged Hudson to study Johns’ methods: a direction that led to her immersion in the ancient practice of mixing pigments with hot beeswax to create a variety of effects. Used by artisans since the era of ancient Egypt (important examples include the Fayum mummy portraits, c. 100–300 CE), encaustic can be carved, smoothed like lacquer, or built up like putty. Johns reinvigorated the method with his famous painting Flag (1954–55), mixing wax with strips of newspaper to create an uncanny and iconic image. Hudson found herself inspired by his example.

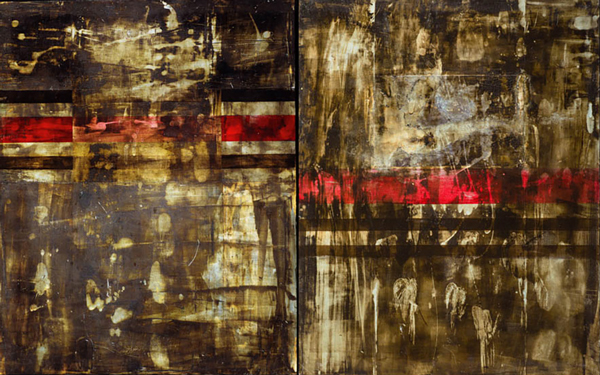

Eric Dolphy’s House 1/2 (2010). Acrylic mixed media on panel (2 panels). 16 x 20 inches. Photograph: Jim McHugh.

“Wax dries so fast,” Hudson said, showing a visitor a radiant and rippling graphite panel. “That’s why you can get layers in between layers, and you can see between the translucency. It’s like in music, that silence that’s in between the notes, in between spaces, that you want to capture. A lot of my work is about revealing and unrevealing, and then covering up again. It’s a back and forth.”

As Hudson talks about her practice, she often circles back to the revelations that occur in music. Her longtime passion for jazz inspired one of the pieces that starred in the CAAM show: Eric Dolphy’s House 1/2 (2010) is a beautiful burned-brown mixed-media diptych with a strip of fire-engine red cutting through a charred-looking landscape. This work is a meditation on the Los Angeles home of American jazz great Dolphy, which Dolphy had used as a studio. It was turned into a community center after his death, but the house then burned in the 1992 uprisings triggered by the acquittal of four police officers filmed brutally beating Rodney King.

“It was such an important historical site,” Hudson said. “[John] Coltrane recorded there, and so did [Charles] Mingus, and Miles Davis was coming by. And then after Dolphy died [the house was destroyed]. So the painting’s a memorial piece.”

Roam (2015). Encaustic on panel. 5 x 7 inches. Photograph: Jim McHugh.

In the studio, the LA sunlight glimmered across gray-black panels that looked like the roiling ocean and a lichen-dappled forest floor. A pink canvas revealed a mottled rose that resembled tender flesh. One round painting glowed cerulean, like an unharmed planet. In all of these works, materiality becomes a strategy for cementing life and history into durable forms, even as they slip away on account of catastrophes both natural and human-made.

Hudson reached down and grazed her fingers gently over the circular blue painting.

“The translucent layers of encaustic investigate these systems of things that were there before, and things that will exist, and things that keep moving forward,” she said, smilingly slightly. “There’s a philosophical aspect as well.”