The Vincent Price Art Museum has mounted an ambitious and idiosyncratic survey of a little-known slice of Los Angeles art history. “Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art,” curated by Dr. C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz, sheds light on the artist’s practice and his ersatz school. Butch Gardens, the school’s namesake, was a raucous ’70s gay bar on Sunset Boulevard—I can attest to its animated scene—that hosted the performance shenanigans of artist Robert Legorreta, also known as “Cyclona,” among others. The project’s allusion to Busch Gardens, the Los Angeles brewery and amusement park that was in operation during the same time, was a wry parodic reference.

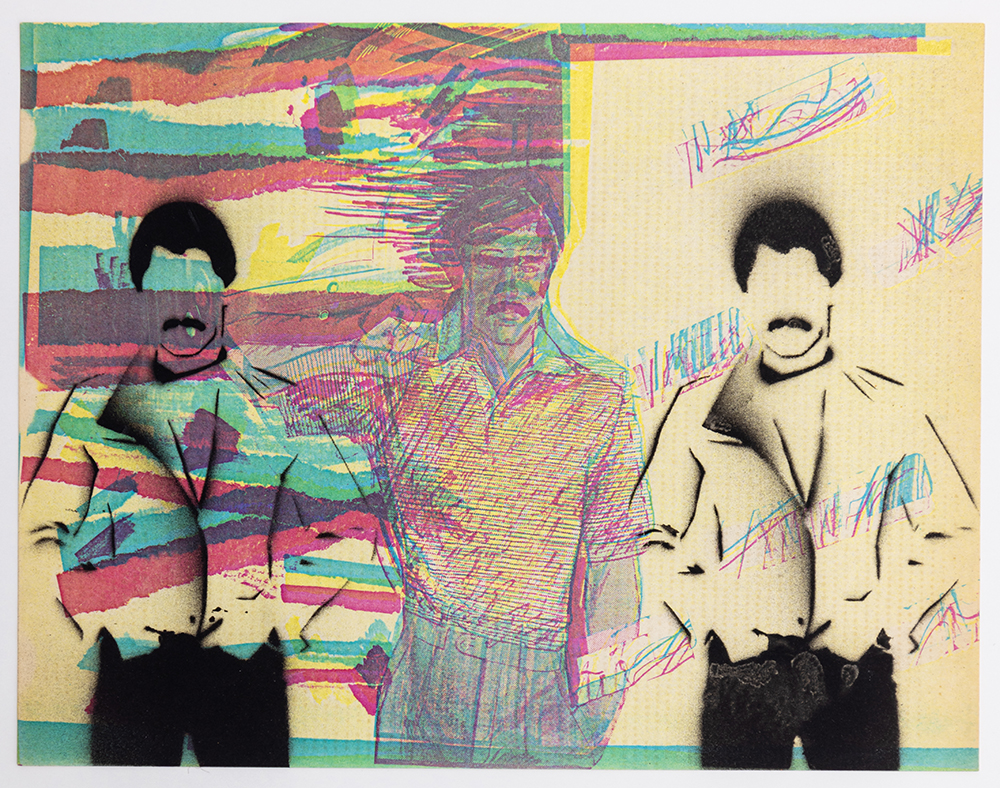

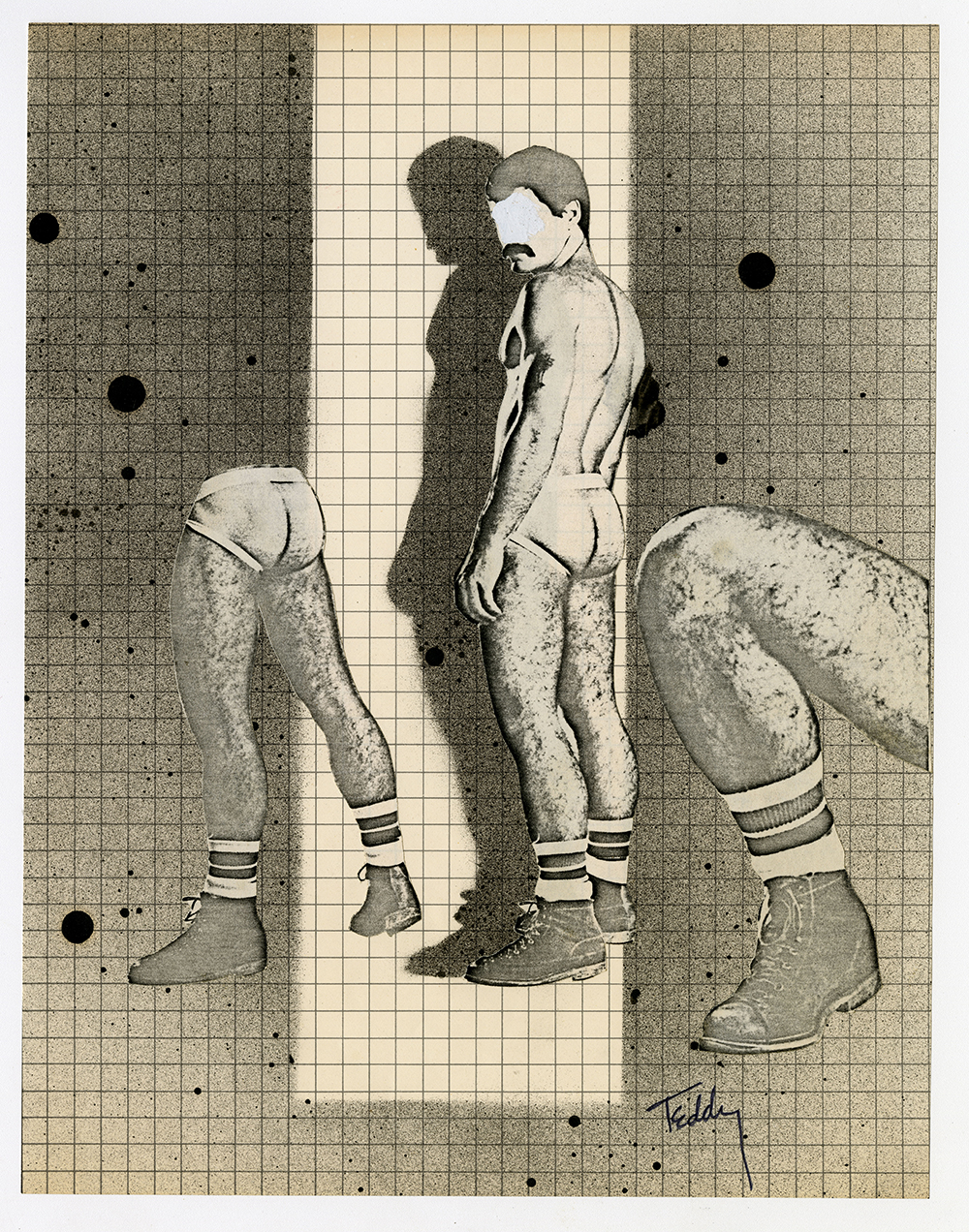

Most of the works on view were gleaned from Sandoval’s estate and span the late 1970s–80s, a seminal, coming-of-age era for the queer Chicano artist, with the exhibition highlighting his works on paper—prints, drawings, artist photocopies and mail art—as well as his ceramics. At some point Sandoval began employing what came to be his signature style: portraits of faceless men with the fulsome, prominent mustaches that were then en vogue.

These works are shrouded in anonymity: One such picture, Untitled (late 1970s–80s) portrays an erotic mise-en-scène, perhaps a fantasy bathhouse, with a muscular, faceless man pondering his options. It’s part allegory, part personal projection—Sandoval celebrated the Latino, gay, macho aesthetic of the moment. Yet he also seemed quite aware of branding in his creation of the Butch Gardens School of Art, whose handle he later utilized as an organizing entity for his practice. Not a school in the traditional sense, the moniker cleverly spoofs the institutional system that deliberately excluded Latinos from the historical art canon and from intellectual discourse.

Teddy Sandoval, Untitled, c. late 1970s-1980s. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas, the Teddy Sandoval Estate.

A particular revelation is his prodigious collection of “Mail Art/Male Art,” reflecting the prevailing ’70s trend of mail-art projects. Installed as a wall-mounted vitrine, the modest-sized works are a euphoric stream-of-consciousness display with an astounding variety of erogenous queer desire. Produced for the most part on card stock, it’s a sweeping manifestation of Sandoval’s multifaceted career. Another highlight is the mixed-media work, Chili Chaps (1978) composed of acrylic, clay, dried beans and metal belt buckle with appliquéd imagery. The work both honors and injects humor into the sometimes competing vaquero and queer sensibilities the artist drew from. Sandoval also encouraged collaboration with his peers, as evidenced with La Historia de Frida Kahlo (1978), a black-and-white photograph documenting his Kahlo drag persona with Los Angeles artist Gronk. The exhibition attempts to make connections to national and international artists working at the time by including them alongside Sandoval’s work—an intriguing, if diverting, juxtaposition. Some of these artists were known to Sandoval, others not, but the attempted linkage seems aesthetically inspired and ultimately unconvincing.

The totality of the exhibition is a heady and remarkable assemblage of one artist’s generous approach to his artworks, a revelation of the multivalent Sandoval, who is no longer sequestered with his faceless men.