Taryn Simon, widely considered today’s premier conceptual photographer, is essentially an investigative taxonomist. She rose to fame with her series “An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar” (2007), in which she secured access to normally closed-off sites like the lobby of the Central Intelligence Agency, a death row recreational facility in Ohio and Harvard University’s HIV Research Laboratory. Through impassive photographs and extended accompanying texts, Simon exposed the hidden and brought up pointed questions about public policy, health, and morality.

In many of Simon’s projects, a meticulous and methodical process of categorization and display is imposed on the subjects in order to expose larger patterns and relationships. For the excellent Contraband (2010), the artist and her team camped out at John F. Kennedy International Airport for five days to photograph every item seized from passengers and express mail by customs officials: drugs (notably Viagra), tobacco, animal corpses, plants, counterfeit handbags, pirated movies, and other odd substances. With each item shot against a stark white background and then placed into groupings with similar items, Contraband offered a lurid, telling, and mind-boggling examination of the human shadow economy.

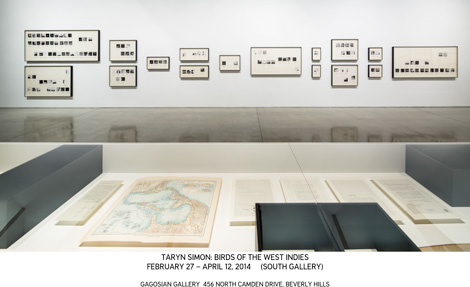

Simon’s most recent project, Birds of the West Indies (2013–14), is the most curious concept she has hatched to date, and probably the least successful. The two-part exhibition revolves around two people named James Bond; the first, the well-known fictional character, and the second, an American ornithologist and author of the definitive 1936 study, Birds of the West Indies. The latter’s name was adopted by Bond author Ian Fleming, who was an avid bird watcher.

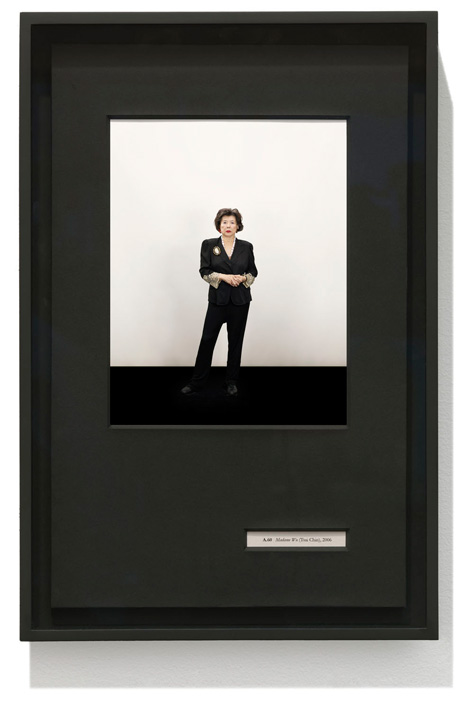

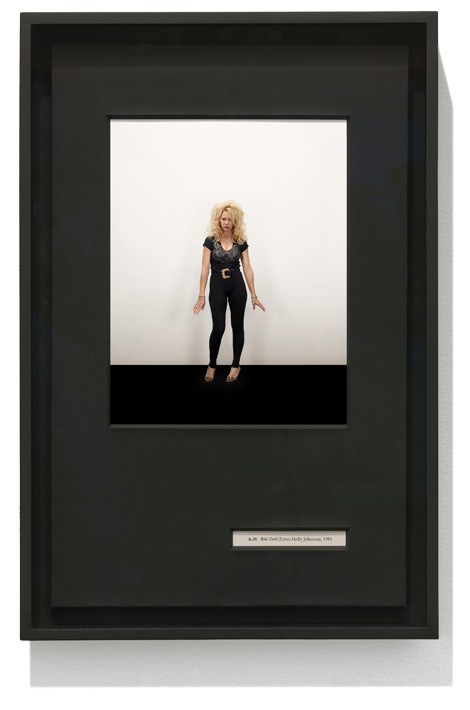

The first room of the exhibition amounts to a commentary on the interchangeable parts that make up the formidable Bond movie franchise. In her signature taxonomic style, Simon shoots and displays the three elements that are most key to Bond’s mystique: women, weapons and vehicles. Actual Bond props were unearthed from private and public sources, and the actresses who played the many Bond women over the years were tracked down and asked to pose in a neutral framework. Some actresses appear multiple times, such as Tsai Chin who played “Ling” in 1967 and “Madame Wu” in 2006, while others who refused to participate, such as Kim Basinger, were marked by empty frames.

Taryn Simon, A.60 Madame Wu (Tsai Chin), 2006, Birds of the West Indies, 2013. © Taryn Simon. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

Simon’s practice works best when her subjects lie down obediently and submit to her relentless analysis, revealing things far beyond their individual objecthood, In this series, there is a leaky subjectivity at work that lends the whole enterprise a disconcerting slippage. Ten out of the 57 actresses who were approached turned Simon down, a record for this wunderkind artist, who has gone on record as saying that their “vanity” has been the single biggest obstacle she has faced in her work to date. The women who did participate were allowed to craft their own presentation for the photographs, utilizing a range of clothing and postures to evoke defiance, glamour, desperation, chutzpah, understatement and so on. This feels like a partial submission and a partial wiggling against the tide, and it doesn’t quite sit right either way—one never knows how to feel about the women’s presence here.

Taryn Simon, A.31 Bibi-Dahl (Lynn Holly Johnson), 1981, Birds of the West Indies, 2013. © Taryn Simon. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

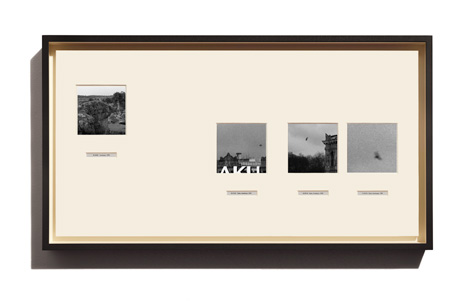

In the second room, Simon seems to be acknowledging her own role as a field scientist and conflating her identity with that of Bond the ornithologist. In a long series of wall-mounted still photographs, she goes “bird watching” in the Bond movies, tracking down and capturing every bird or group of birds that randomly appears in the background of scenes and labeling them according to the fictional places in which they appeared (Crab Key, SPECTRE Island, etc.). The room is then rounded out with a collection of artifacts from the ornithologist’s archives, including letters, receipts, maps, field notes and actual bird specimens that he had preserved and tagged. These are displayed in vitrines, effectively rendering Bond himself a specimen.

Unfortunately, all that this second room serves to expose is, at best, a moment of poor judgment on the part of the artist, and at worst, a possible case of obsessive-compulsive disorder gone unchecked. We as viewers don’t really get anything out of looking at endless pictures of random birds flying through scenes from Bond movies, or poring over banal correspondences from the Bond archives (one deals with transferring his auto insurance to a new 1967 Buick LeSabre)—other than, perhaps, a concern for Simon’s mental health. The subjects in this exhibition don’t bloom or reveal, as they do in Simon’s best work; they only confuse and dismay.