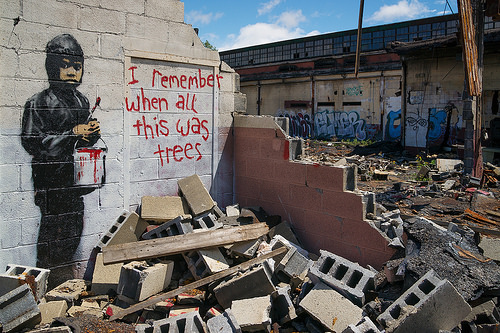

In the 1970s, The East Los Streetscapers promoted the idea that graffiti muralism was part of the struggle to claim urban space. This concept was shared by the Los Angeles Fine Art Squad, a group of artists also taking art to the street using murals. This activist...