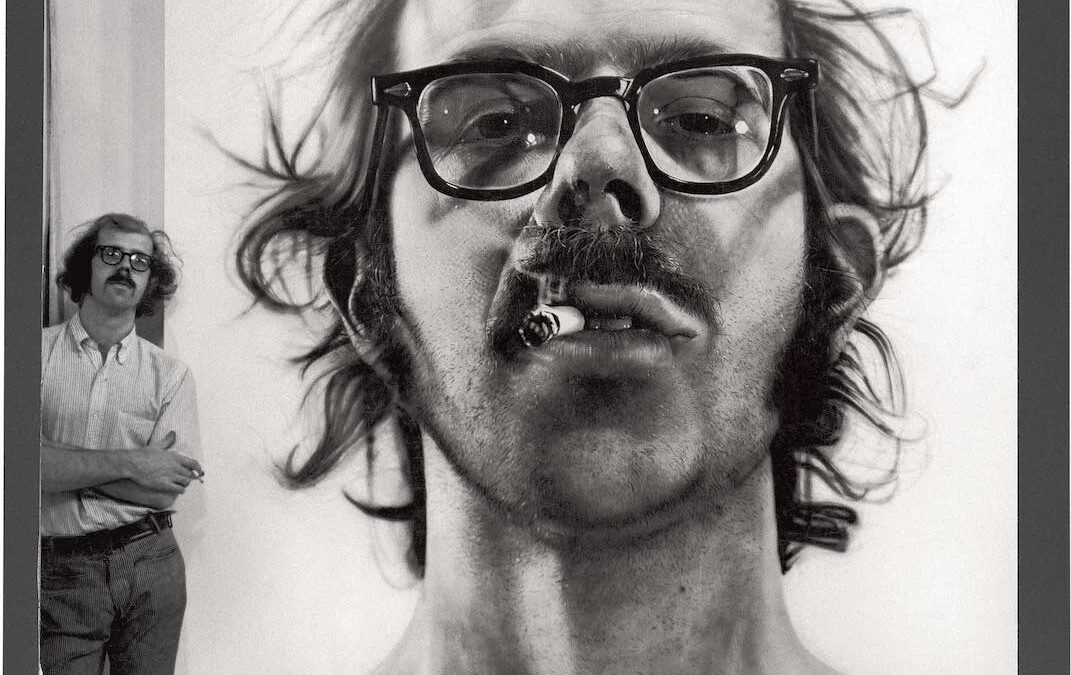

Almost all of Chuck Close’s paintings were based on photographs he took himself. In the mid-1980s, when I was a curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, I contacted Close with the first museum proposal he had had to do an exhibition of the photographs....

R.I.P. Chuck Close Remembering the great self-portraitist

read more