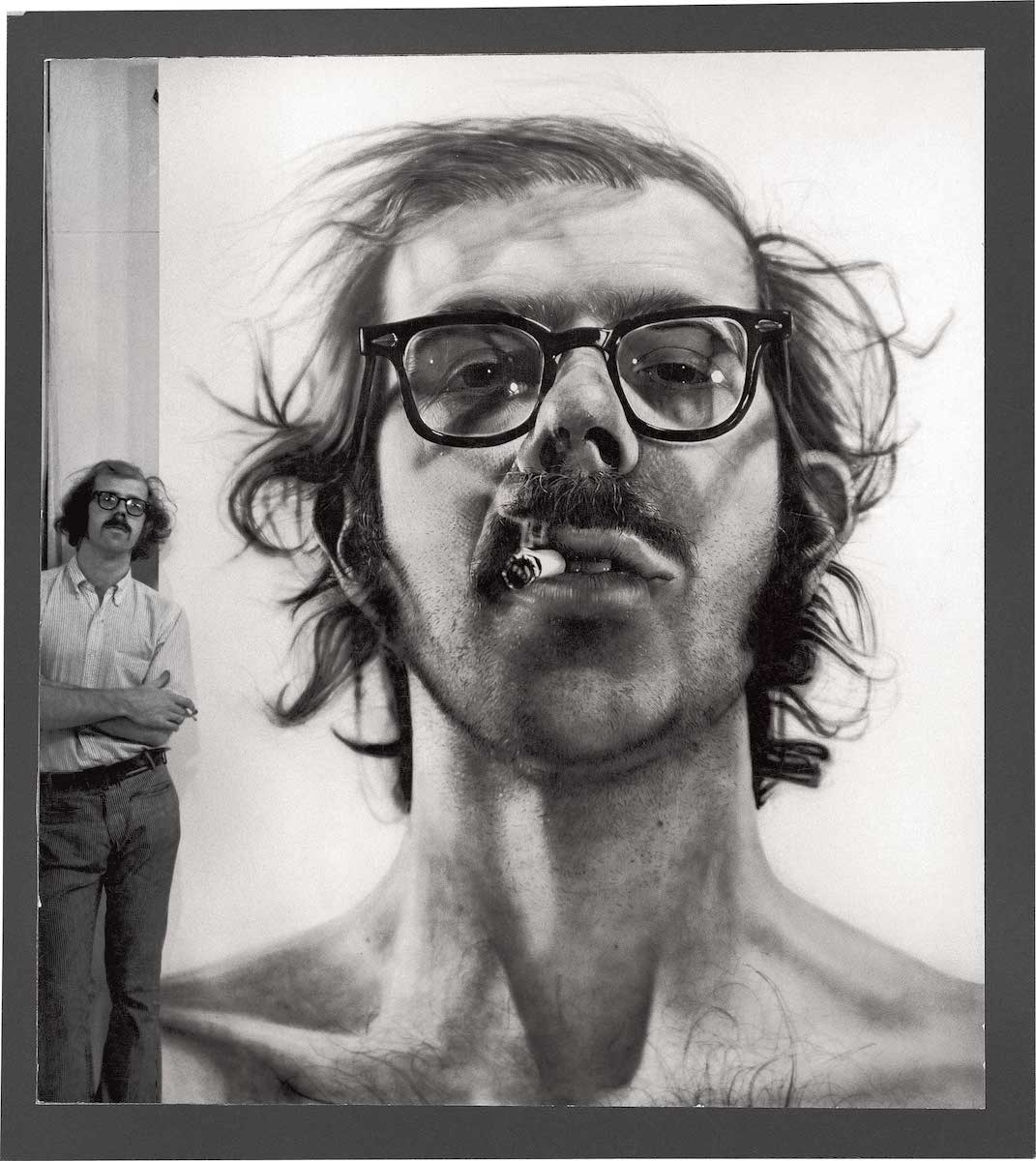

Almost all of Chuck Close’s paintings were based on photographs he took himself. In the mid-1980s, when I was a curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, I contacted Close with the first museum proposal he had had to do an exhibition of the photographs. He was at the time in a New York hospital convalescing from the collapse of an artery in his spine. He was nevertheless responsive to the idea, so I went to see him in the hospital, and the exhibition came to fruition some months later.

Close’s most recent portrait paintings had been based on photographs that were life-size made by an enormous Polaroid camera. Close could stand inside the camera while each exposure was made so he could make an instantaneous decision which one to print as a basis for his painting of the subject.

These were the photographs – a mix of portraits and some nude studies – from which the exhibition was primarily drawn. The impression this may have made that he was recuperating along with his art work was misleading, however, for he was now permanently paralyzed from the his shoulders down. Yet he managed to overcome even this tragedy by having a brush taped in his hand and then wielding it by a combination of physical therapy and sheer grit, until he had restored his painting to the point at which the massive stroke had interrupted it.

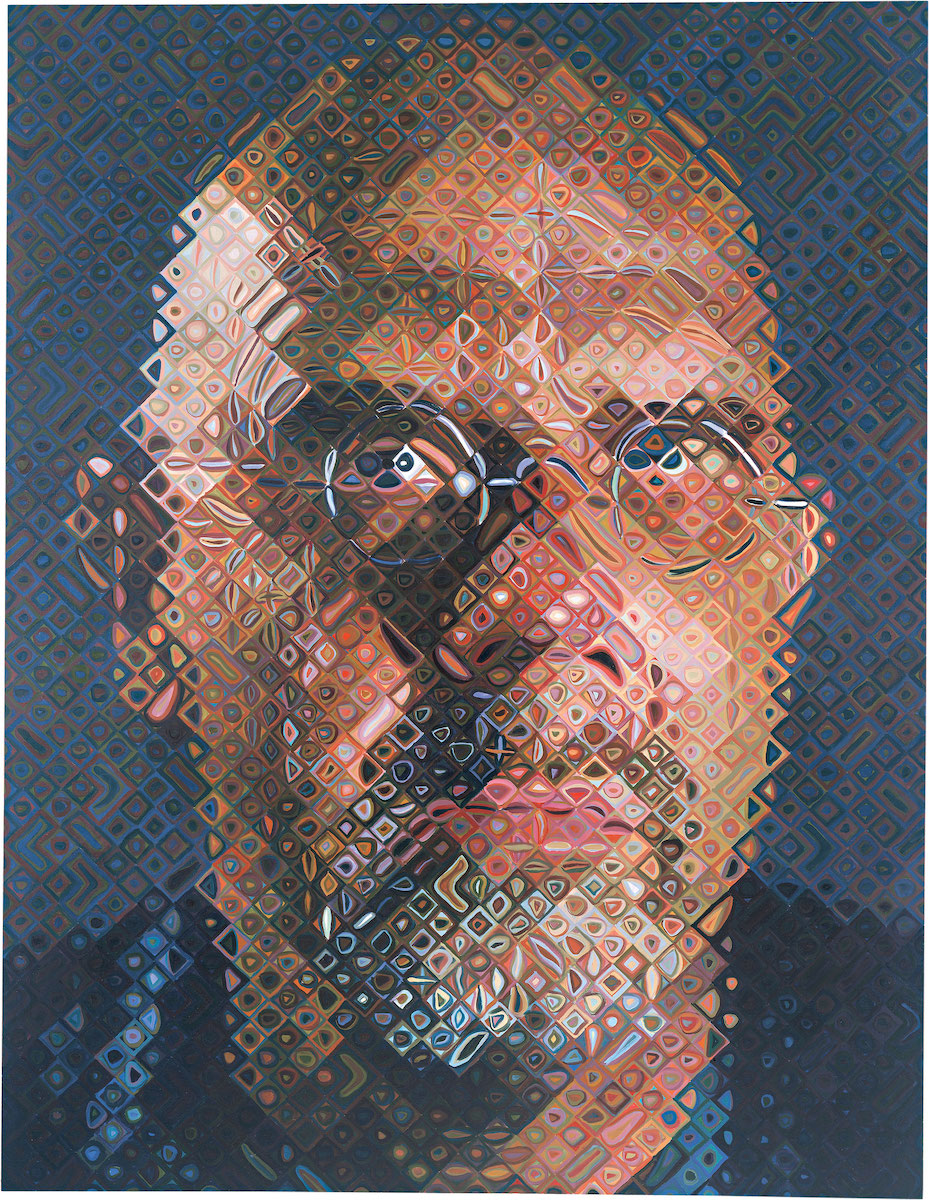

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait, 2005

Around a decade after the exhibition of life-size Polaroids, I got Close involved with making photographic images that were the opposite in both size and history. They were modern-day daguerreotypes, a 19th-century portrait process creating a unique image on a chemically treated metal plate only a few inches in size. This became yet another process Close reinvented as signature images all his own.

Since then I had stayed in touch with Close, visiting him in his Soho-adjacent studio whenever I was in town. The most recent visit, in the fall two years ago, was a melancholy one. The first thing he told me was that his first wife and oldest daughter would no longer speak to him, nor would his recent, second wife who had also, now, divorced him. Among the reasons for all this rejection were recent advances he’d made toward young women who were the models for nude photographs he was now making, and who had also rejected him.

While such bad behavior on Close’s part cannot be forgiven or glossed over, neither should the fact that, despite his personal shortcomings, he was a genius who bent the history of art in all the media he adopted to his own, unique will.

Often, too often, it’s not best to come close to artists. Outside of their work, which at its best touches on the infinite, they are otherwise

all to finite.