Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: nude photography

-

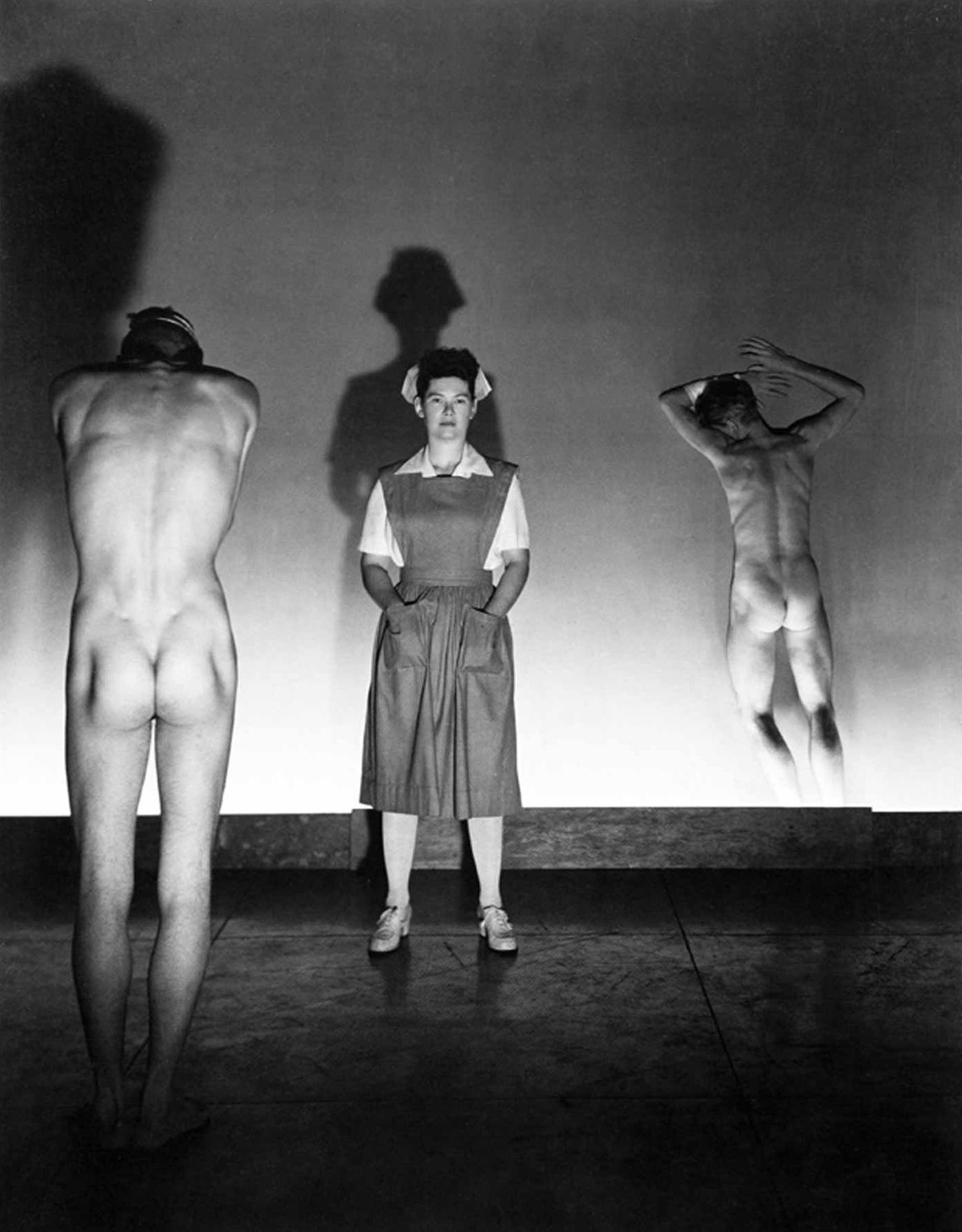

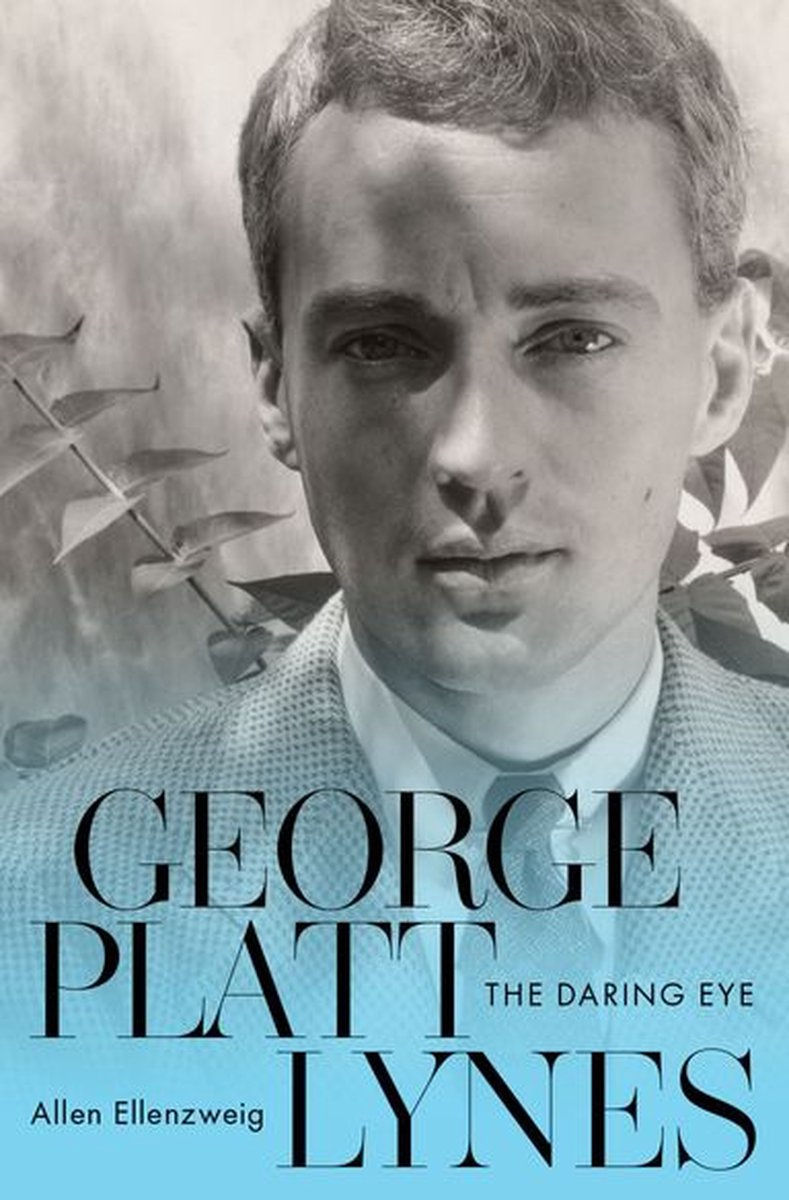

BOOKS: Forbidden Photos

George Platt Lynes’ Daring EyeIn 1981 a new photography monograph appeared that seemed like an artifact from a parallel universe. The cover was a studio shot of a nurse flanked by two nude men. Many of the photos in the book depicted nude men in potentially gay scenarios. It had only become legal to mail this book in the United States ten years earlier. If you were a scholar of the history of photography you might have recognized the photographer’s name from his portrait and ballet photos. But this work caught the world by surprise. Although beefcake photography had been published before in magazines, none of it had the look of something that had been produced by a movie studio. Suddenly people wanted to know who had taken these photos. Unfortunately, the photographer had died 26 years earlier, and hadn’t been famous enough to merit a biography while he was alive. Thanks to an admirable feat of detective work, we now have a pretty detailed account of the photographer’s life.

George Platt Lynes didn’t start by wanting to be a visual artist or photographer. His heart was in the written word. He initially aspired to being a small press publisher and an author. He even owned a bookstore at one point. His original reason for taking photos was to hang them in his bookstore. His love of the written word was on display in the constant flow of letters that he sent and received. On a family trip to France when he was 18, he managed to meet Gertrude Stein. A rich source of material for this book comes from his brother, who wrote an unpublished autobiography of George in the spirit of Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Anybody who is interested in Stein lore will get an interesting perspective of a not yet famous Stein hustling Lynes to get her a publisher (or to publish her himself). George became a regular visitor to Stein’s salons, which caused him to photograph all of the famous people he was meeting. He took what is considered one of the seminal portraits of Stein. Her salon launched him into the right circles, and one of his publishing ventures included a book by Ernest Hemmingway.

Although he was born in 1907, he never seems to have been in the closet. His father was an attorney who became disenchanted with the law and became a minister. He managed to get postings to good neighborhoods, so George grew up in nicer surroundings than a minister’s salary might afford. His mother had a teaching degree, so both parents had experienced higher education. His father loved opera and had worked as an usher during his theological training in order to watch operas for free. As he came into his own, George was an avid attendee of operas, ballets and plays. When he proved to be less overtly manly than his juvenile peers, he would claim to be a Russian prince, whose identity was a highly regarded secret. His parents, sensing that he was different, decided to send him to boarding school in order to offer him some male role models. The school called their approach “muscular Christianity”. Various teachers and classmates compared him to Oscar Wilde, and classmate Lincoln Kirsten remembered him as a “foppish freak”. Once his father was resigned to the fact that his son wasn’t going to pursue a traditional career, he gifted George with his first professional camera.

Cover image of the book. At the tender age of 20 he met and fell in love with author Monroe Wheeler. The problem was that Wheeler was already devoted to another man. George solved the problem by grafting himself onto the existing relationship, making them an early throuple. Once they all decided to live together, their apartment became ground zero for the smart set in Manhattan. The relationship lasted for nearly 20 years. His earliest photographic work was portraits. He had access to a who’s who of the mid 20th century, and his social whirl always had a bit of calculation about who might sit for a portrait (or take off their clothes for a more private photo. He convinced Tennessee Williams and Yul Brenner to pose naked) He paid the bills by doing fashion photography, and his ballet photography brought in income. Money was always an issue. First his father and then his younger brother were often called upon to keep the wolf from the door. It can be head spinning to read that while he is up to his eyeballs in debt, he needs to run home and change into his top hat and tails for the opera.

Eventually the IRS ended his long streak of good luck. In 1952 the entire contents of his studio were auctioned off to pay back taxes. (Richard Avedon ended up with his studio) His younger brother brought in proxy bidders to buy back his camera and essential equipment. But he never recovered his mojo, and died within three years of lung cancer. Sensing his own mortality, he made arrangements to place the nude photo work with the Kinsey Institute.

This book is rich in details about his life and the world that produced him. It is the sort of book that you can open to a random page and be caught by some detail that will have you racing to Google to learn more. There are photos throughout the book that offer relevant visuals. The footnotes are copious and often fascinating in their own right. For anybody looking to study or recreate gay life in the mid 20th century, this is a deluxe road map.

George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye

by Allen Ellenzweig

664 pages, illustrated

Oxford University Press

-

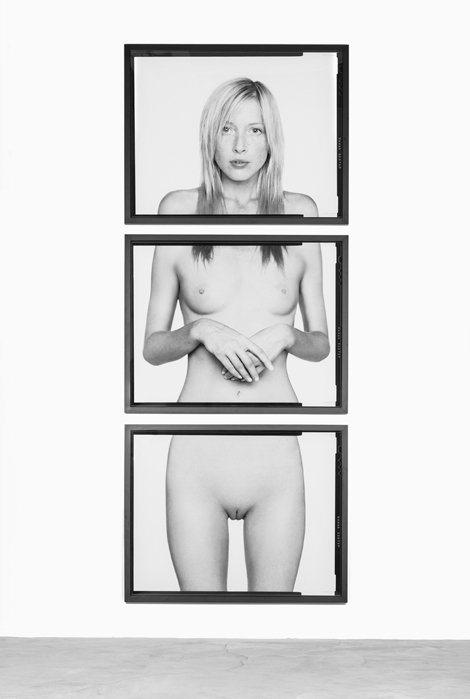

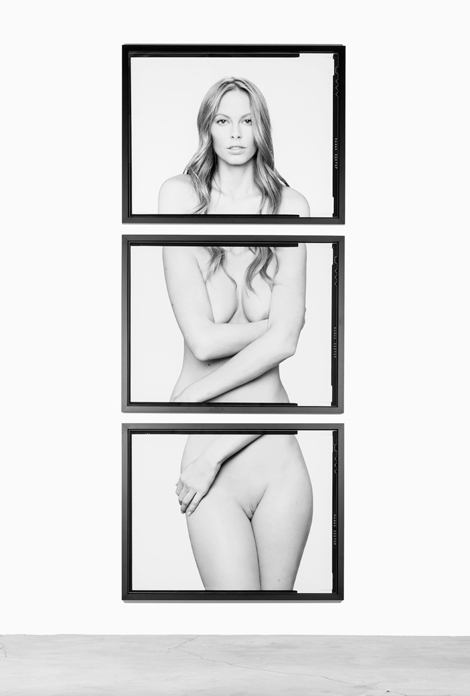

Samuel Bayer: Diptychs and Triptychs

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Samuel Bayer’s series of photographic “Triptychs,” recently on view at ACE Gallery Beverly Hills, is the complexity of the meditation on desire and representation that they can engender in a [male] viewer. These 16 12-foot studies of nude models, each one fragmented into three vertically arranged and slightly off-register divisions, comprise an uncanny portrait gallery, absolutely compelling in its juxtaposition of apparent physical presence and brilliantly realized artifice. Like the notorious 4th-century Aphrodite of Praxiteles, these women are simultaneously incarnate objects of male sexual desire and masters of that liminal zone that marks off the external physicality of the body from the internal subjectivity of the self, a situation they share, for example, with Manet’s Olympia as well as the antique goddess.

The installation itself, beautifully spaced around the gallery’s central exhibition space, gave something of the feeling of standing inside a strange and wonderful sacred space, perhaps a temple, where the image of the cult statue had been replaced and replicated by the monumental figures that functioned also as the enclosing colonnade. But it was the individual portraits themselves that exercised the real power: the power to structure, almost to enforce, a complex and ambivalently charged experience.

Samuel Bayer, Janelle #1, 2012 Monumental in size, each “Triptych” has also something of the look and feel of sculpture, as though the bodies might be cool to the touch, like marble, or smooth and slick like mahogany or ebony. And they seem to carry their weight with ease and grace, despite the potentially awkward lack of feet, a fragmentation that, in the overall pictorial scheme, makes much less difference than it might This is I think a clever formal choice related to the size and shape of the individual visual fields (in turn conditioned by the size of the photographic plates) as well as the decision to “open up” the transitional space between field and field—a decision that also sets up a nice back-and-forth between perceptions of fragmentation and integration, part(s) and whole.

The body types of Bayer’s models are quite varied. Their ethnicities are global in scope. Their “personalities” (at least in so far as we can read them from details of pose, poise, musculature, expression and overall self-presentation) are likewise strikingly distinct, although the artist has posed his subjects according to a few basic formulae, mostly more-or-less completely frontal, but subtly modulated from one model to the next. Taken as a group, they might be said to exemplify Albrecht Dürer’s famous admission that “God alone . . . knows the secret of absolute beauty.” They are all “beautiful,” and in that way all can be desired, but in turn they reveal the multiplicity, the fragmentation of that desire, and the protean nature(s) that desire’s objects can assume. (These observations perhaps in turn raise questions of sexual politics that are unfortunately beyond the scope of my brief here.)

But what really ties Bayer’s models all together, the one thing (aside from their evident nakedness) that all share is the “curious” fact of their shaved genitalia. This was the one aspect of the photos by which I was taken slightly aback, especially given it’s rather “in your face” position in the center of the lowest panel in each portrait. For me, this naked sexuality actually served as a spur to turn my attention upward, whether to escape an awkward and objectifying encounter or simply to avoid the public articulation of a very private gaze. One might, however, legitimately ask of these rather confrontational panels, “Why?”

Samuel Bayer, Kristina #1, 2012 I can think of at least a couple of possible answers beyond my own momentary embarrassment. First, the representation of public hair was “prohibited” by convention in work produced within the broadly classical tradition from antiquity until the 19th century and beyond. (For a beautiful contemporary example of such a work, see Sara VanDerBeek’s Roman Woman VII, a photo now on view in her exhibition at Metro Pictures in New York.) Second, the workaday utility of shaved genitals, airbrush artists notwithstanding, should become immediately evident to anyone who flips through a Victoria’s secret catalog, this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, the current issue of Maxim, or any high end fashion magazine like Vogue. Beyond that however, it has also become de rigueur in the world of porn. So the possible resonances are several, and to a certain extent contradictory. Perhaps best at this point simply to take a fairly “conservative” position: that the power of naked, raw sexuality is something embedded deep within us, almost as the ground from which grow both the kind of self-fashioning we see in Bayer’s model’s, and the kind of artifice that both enables and records those senses of self.

All of this, however, is only a preliminary to the articulation of a much more intimate, and historically resonant, set of relationships. Although all the models seem clearly to be professionals, denizens of the world of haute couture and runway fashion, (a world haunted also by the artist’s photographic touchstones Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton) Bayer presents the models with a kind of unsparing, unforgiving directness. Up-close and almost preternaturally personal, each model’s body presents an extraordinary physical topography, the object of an exploring, possessing and tactile gaze. Meanwhile, each face presents a unique personality: wary, intimate, delighted, assertive, powerful—and this personality animates the body as well, recuperating the objectification of the gaze with a living, warm and vibrant presence, but a presence carefully fashioned by means of a consummate artifice.

On the one hand, this artifice is clearly a matter of the individual model’s sense of self and skill at self-presentation. After all, these attractive young women live in a world where that kind of flawlessly artificed self-presentation is simply a fact of professional, and I suspect also (eventually) of personal life. So whether what we see is a pose of imagined innocence and feigned yet as-if naïve self-exposure, as in Janelle #01 (2012) or instead a pose that, whether consciously or not, echoes (although with a sly inversion of concealment and revelation) that of Praxiteles’ Aphrodite herself, as in Kristina #01 (2012) what we get is quite literally a pose: a presence at once personal and coded, constructed and projected.

And this means, on the other hand, that every image, every representation of a living and self-sufficient presence, arises at least in part from a collaboration between model and artist. So every image establishes a relationship that plays out in experience at once between model and viewer, artist and critic. These relationships are inextricably linked, but hardly identical. I can differentiate between my response to Janelle’s wary yet utterly open faux-innocence, and my response to Bayer’s skill as an artist in (crafting and) capturing that self-projection. Still—if I did not find “Janelle” so achingly attractive, I might well find Bayer a less skillful photographer; I would certainly find him skillful in some different way.

Samuel Bayer, Installation shot, courtesy ACE gallery Finally, as someone interested both personally and professionally in the history of visual culture, I must return briefly to what is arguably the most resonant image in the entire series: Kristina # 1. As a model, Kristina seems to have arrived at her pose as if by chance or simple physical reflex. And her self-presentation is interestingly ambivalent. Her expression is relaxed, at ease, in control; but her body itself seems, if not tense, then a little drawn in on itself. At the same time, the pose recalls without duplicating that of Aphrodite, as given originally in the version by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles that became normative for the presentation… of what, exactly? On the one hand, Aphrodite was, in simplest terms, the incarnation of male sexual desire, the ultimate available object. On the other, she was a dangerous and self-possessed goddess, both powerful and coy; and posed by Praxiteles with a skill designed simultaneously to reveal and conceal that power, to suggest rather than define the complexity of sexuality, the ambivalence of desire—and, as if in passing, the intricacy of my own relationship with “Kristina.” That relationship, of course, owes much as well to the skill of Samuel Bayer, whose work in this series of photographs engages those same complexities and those same ambivalences which mark the playing out of desire in life as well as in art.

ACE Gallery: Samuel Bayer: Diptychs and Triptychs, ran from March 3 to April 27, 2013; acegallery.net