Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Mixed Media

-

RICHMOND, VA: Diego Sanchez

VISUAL INFORMATION“One of the things I teach my kids is to be playful in their approach,” says painter and teacher Diego Sanchez. This freedom to experiment takes the pressure off and opens up the work in unexpected directions. It’s an attitude that has served Sanchez well in his own practice.

Sanchez lives and works around Richmond, Virginia, a city with a vibrant art scene. His story is not just about becoming a successful artist, it’s also an inspiring account of an immigrant starting with nothing and rising up through the ranks of his profession. Born in Bogotá, Colombia, Sanchez came to the US in 1980 at the age of 15. His father, a judge, had refused to cave to pressure from drug cartels. Fleeing for their lives, the family ended up in Northern Virginia. Sanchez, who had opted to study French at school in Colombia, spoke no English. It was an art class that changed everything, providing a means of communication. “I realized with art, you didn’t need English or French, anyone could get it,” he says.

Composition #6, 9×12 inches, mixed media on paper, 2021 After graduating from high school, with no money for college, Sanchez enlisted in the army. On completion of his military service and college degree, he attended Virginia Commonwealth University School of Arts, one of the best art schools in the country, where he received his MFA.

In the years following, Sanchez cobbled together a career with teaching gigs at various places around Richmond. His first full-time position was at Virginia Union University (one of the oldest historically Black institutions in Virginia), where he taught for five years. Eventually, he was offered a position at St. Catherine’s School (a distinguished private girls’ school), where he has been teaching for over 20 years. During the summer, he leads art classes at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VFMA) and at Richmond’s Visual Art Center.

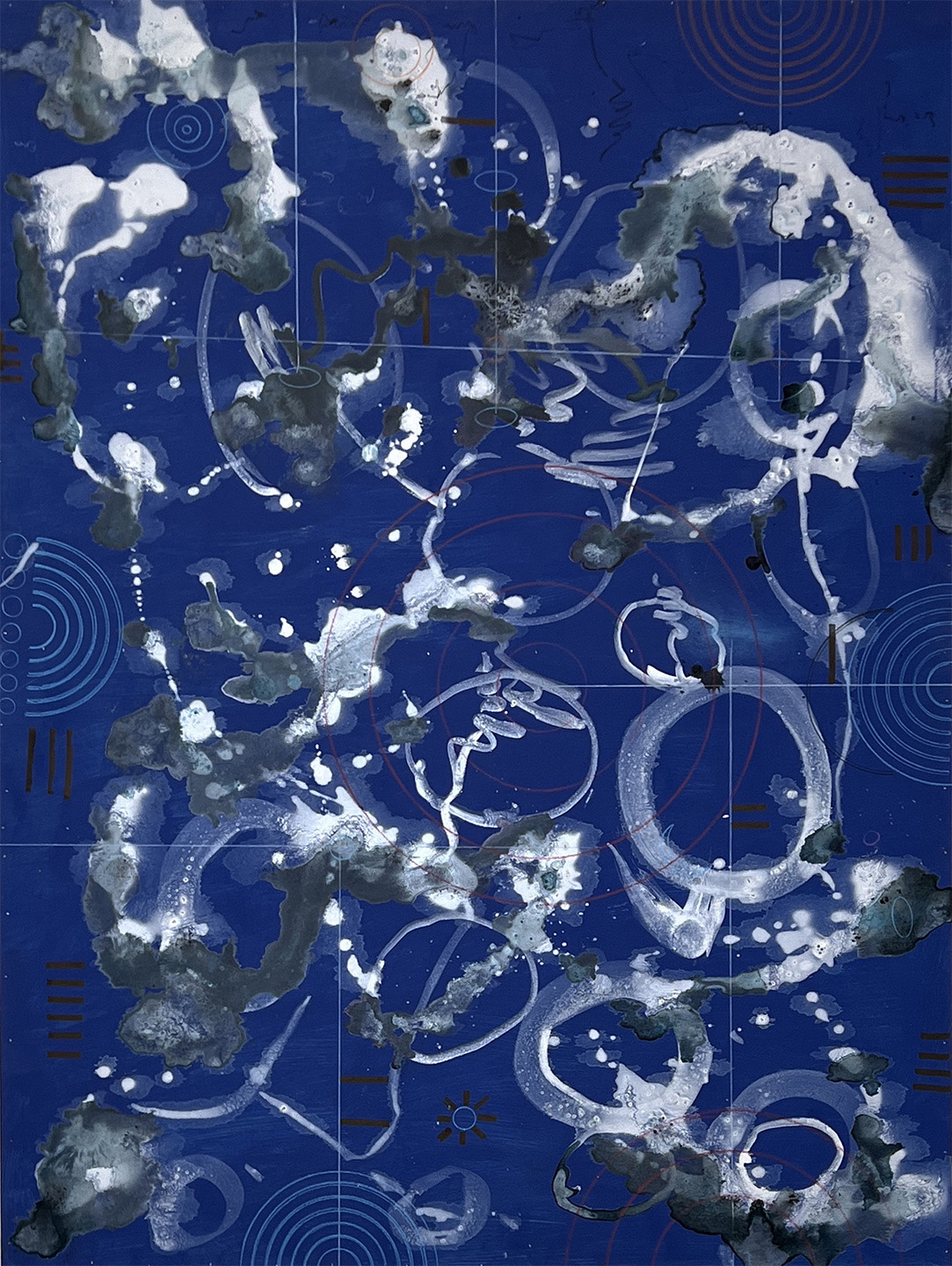

current work in progress, 48×36 inches, mixed media on panel, 2022 One of the first things you notice about Sanchez’ work is the surfaces. He uses a water base to develop them, coming back with layers of oil and cold wax. He also uses unorthodox materials—coffee to stain and soap mixed with pigment to create bubbles of paint that burst and leave behind nebulous rings of color. He likes playing with visual information. Sometimes he starts by creating realistic space and then paints something flat on it or adds patterns or text. “To me, a painting is a record of whatever is happening at the time. For instance, sometimes when I’m working in my studio, my wife will say, “Hey, can you pick up some milk?” So, I’ll jot down, pick up milk, on the work. I may cover it up later, but little glimpses of my life remain, becoming part of the painting.”

To center and relax during the stressful months of the pandemic, Sanchez started putting lines on paper. “I used this wonderful walnut ink. I love the earthy color, the opacity, the way it handles. I first created a simple structure of lines and then came back with the grid. I did a whole bunch of them, combining some with cold wax. It was like making a structure out of chaos.”

Composition #124, 32×40 inches, mixed media on panel, 2021 His work was changing, and with an upcoming show on the horizon, he set himself the challenge of doing 100 small pieces on paper. These gave him ideas on how to move forward, shifting from the handsome arrangements of geometric shapes to looser compositions that incorporate amorphous forms and interesting color pairings. In these works, texture and pattern possess an enhanced earthiness that imparts soul.

According to Dr. Michael R. Taylor, chief curator and deputy director for art and education of the VMFA, “Diego Sanchez is one of the most exciting and respected artists working in Richmond today, the museum loves his work, and we were proud to acquire Composition #76 for the collection in 2018.” Certainly, the measure of success is the acquisition of your work by a major museum, but Sanchez, like many famous artists before him, has the added coup of having his own merch available in the museum shop, which carries a puzzle and socks based on the acquired painting. Not bad for a kid who, at 15, had to start all over again from square one.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Museum of Art and History Lancaster

Group Exhibition “Activation”Comprising seven different exhibitions, “Activation” is an exciting series of works from six individual artists as well as a selection of activist graphics. Featured artists and their exhibitions include Mark Steven Greenfield, April Bey, Carla Jay Harris, Keith Collins, Paul Stephen Benjamin, Sergio Hernandez and the Collection of Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Taken individually and as a whole, the exhibitions offer an invigorating mix of mediums and styles. Bey’s lush The Opulent Blerd uses tactile mediums and vivid color to express power dynamics, including that of the advertising and fashion industries regarding people of color. Smart, witty and trenchant, Bey’s exquisitely constructed work is also simply beautiful.

April Bey, The Opulent Blerd Equally lovely are the gilded, fantastical images of Harris’ A Season in the Wilderness. Infused with light and a sense of magic, Harris shapes boldly hued visuals myths both mysterious and captivating. With gold leaf elements that mirror that of Byzantine icons, Greenfield’s “A Survey, 2001-2021″ creates powerful paintings that subvert negative stereotypes about Black people and culture. Like Bey and Harris, a fierceness in palette matches passion for his subjects, serving as a framework for a message of pride, hope, achievement and sacrifice.

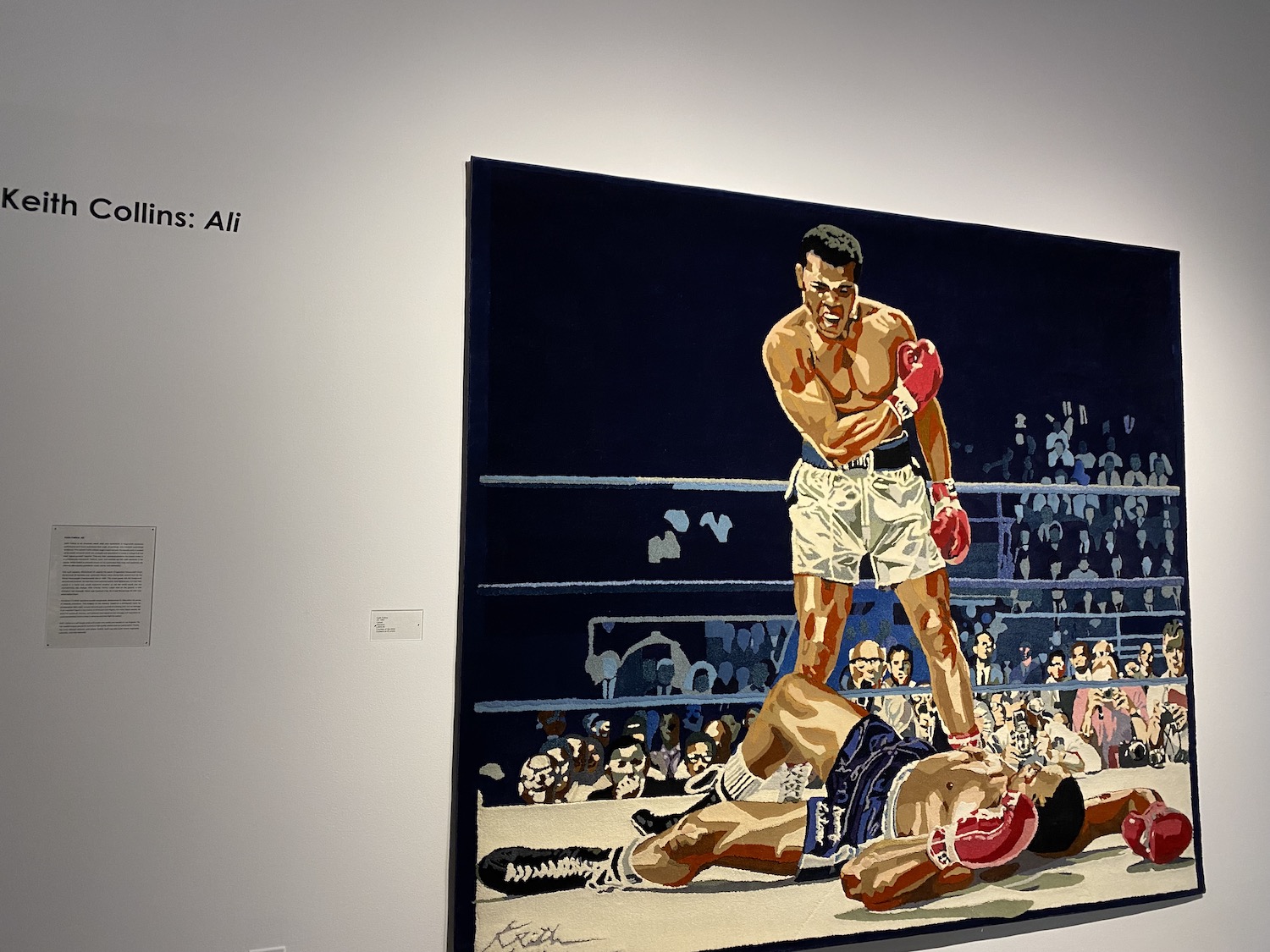

Mark Steven Greenfield, “A Survey, 2001-2021″ , photo by Genie Davis. Collins’ incredible use of repurposed material to create tapestry is on full display with Ali, a woven miracle of second-hand fiber creating a visceral tribute to the great fighter —and first-class art. Audio and video elements are also approached as woven material, with Benjamin’s stirring Oh Say (Remix), combining iconic American imagery with voices of black artists performing The Star-Spangled Banner.

Keith Collins Ali on view at MOAH. Photo by Genie Davis. Hernandez’ collection of work is also potent, presenting satiric graphic and comic art in Chicano Time Capsule, Nelli Quitoani; a variety of graphic fine artists’ work is displayed in “What Would You Say.” These two exhibitions, while less visually galvanizing than the others on displa, nonetheless richly round out a show soaring with imagination and beauty while educating viewers and redefining its subject matter with a sense of purpose and change.

MOAH is located at 665 W Lancaster Blvd, Lancaster, open Tuesday-Sunday.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Leigh Salgado

Launch Gallery“As the World Turns” is an apt title for Leigh Salgado’s fourth solo exhibition at Launch Gallery. Many of the graceful works are circular, globe-like. A lush world of beauty that also evokes ideas of the circular nature of life: our annual passage around the sun, and speaks to the power of female strength in nature.

The painted, collaged, and cut-paper works are intricately mandala-like. The layers of each hand-cut paper and acrylic piece are as delicate as butterfly wings held in place by tough yet fragile spider webs.

Leigh Salgado, In & Out, 2021 Creating almost impossibly perfect patterns in medium and palette, Salgado juxtaposes the transitory nature of life and its abiding existence, and both the poignancy and power of its beauty.

Her lacy patterns are sensual and tactile, with painted elements varied in each piece. In Secret Garden, her work is almost like stained-glass, rich and deep. Be Still My Heart is more of a mosaic, with its image of an actual heart blossoming like a flower. And speaking of flowers, Heartbreaker makes muted blossoms grow around the image of a woman’s lingerie; the darker, more muted palette seems like an elegy for a femme fatale who has cast that role away. In and Out carries an autumnal color palette and reveals broken handcuffs, once again calling to mind the idea of a role or a relationship cast aside.

Leigh Salgado, Ballgown, 2021 Ballgown, with a golden background and a dress seemingly made of bubbles, appears to burst the fairy-tale-princess myth into something that doesn’t last, a temporary dream at best.

Leigh Salgado, Red, 2021 Launch Gallery,

ends November 13. -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Louise Nevelson

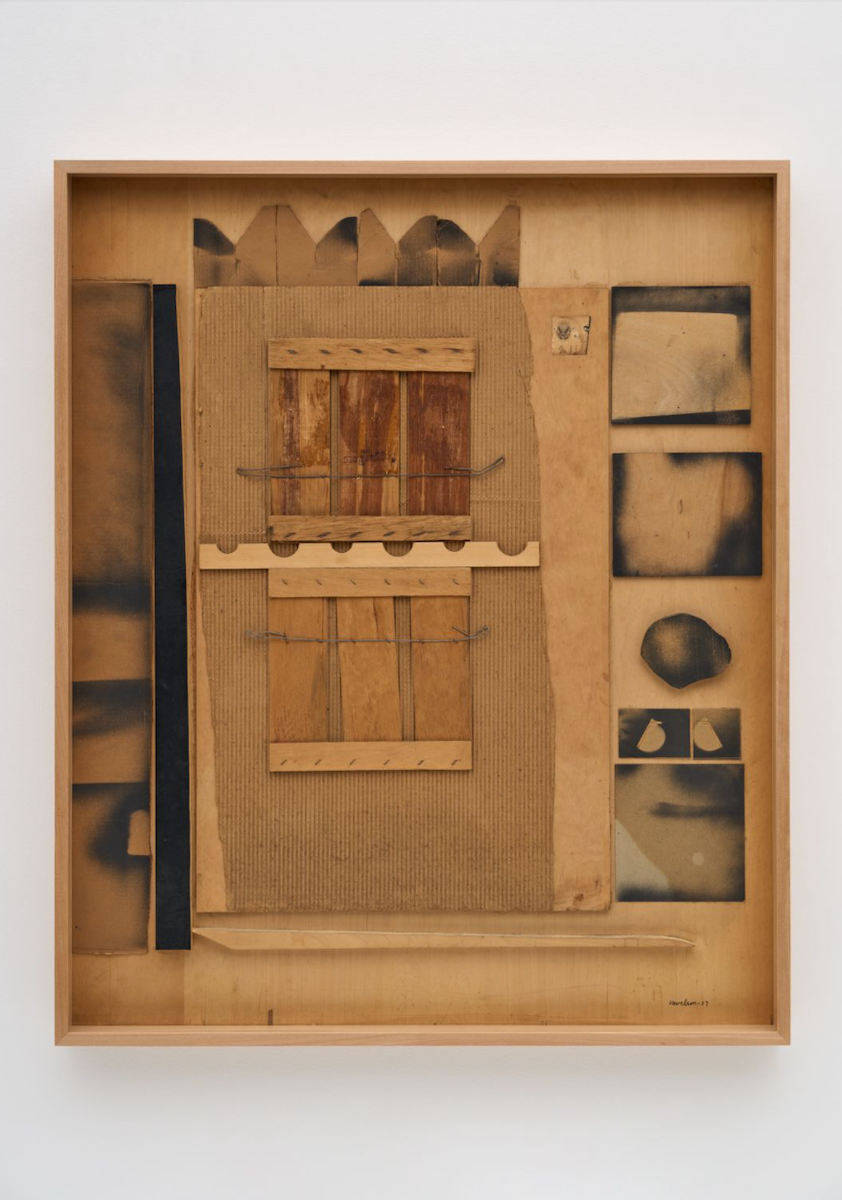

Kayne GriffinFragments of paper, cardboard, wire and foil have all been carefully orchestrated into a space that seems to float seamlessly and coalesce into a compelling quasi-geometric composition in “Collages 1957–1982” by Louise Nevelson. On closer inspection, it becomes clear how much the detritus that was collected from the artist’s environment was carefully smoothed, flattened, cut, torn and arranged—as though it was the most precious material in the world. The clear yet complex set of correlated relationships between the smaller forms and the larger bounding areas radiate a sense of harmony that belies the humble nature of the raw material being deployed. Predominantly monochromatic with some high contrast between white-and-black masses, there are occasional eruptions of color: a bright orange here or a light blue there, but there’s a sense throughout that these compositions are meant to be very even tempered.

While Nevelson’s sculptural works comprise large arrays of decontextualized objects and parts of objects arranged in patterns that are then evenly coded in one color, these smaller studies demonstrate how the artist works her aesthetic prowess on a less massive scale. There is still the kind of somberness to these collages but it is scaled differently so the concern that is worked out on each individual element, be it a fragment from a cigarette pack or part of a wooden crate, is highlighted.

Louise Nevelson, Untitled, 1957 © 2021 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York In Untitled (1957) flanking either side of the central corrugated cardboard panel on which wood panels are wired are smaller scraps of flat cardboard on which rough geometric shapes have been created through spray painting, leaving the forms as negative space defined by the surrounding black paint. Above the central panel the artist has positioned several semi-circular arches that appear almost crown-like. There are tears and regular cuts of these different parts throughout, but it all looks to have been shaped by pushing a determined composition.

The pleasure evinced in viewing these works is determined by both the quiet and controlled orchestration of space and also by entering a very subtle yet decisive imaginative dimension in which the viewer is invited into a space without it ever having to add up to anything other than its exploration.

Louise Nevelson: Collages 1957 – 1982

Kayne Griffin

Through Oct. 30

-

A REAL HORROR SHOW

Ecological Dystopia in Contemporary ArtOur apocalypse is self-inflicted. We gouge at our wounds in acts of self-harm. Our collective anxiety festers as disaster takes hold, yet we remain paralyzed by fear, unable to face our reality. Implausible flames dance on the ocean’s surface; acres of California mountains are scorched black; storms terrorize and devastate our cities. The environmental crisis is no longer looming overhead, it is no longer an abstraction—an unsettling shadow we choose to ignore or hide from—it’s here, screaming!

Artists Max Hooper Schneider, Hugh Hayden, and Kiyan Williams consider the ecological horrors of our past, present and future. These artists explore the intersection of ecology and horror, examining the ways in which “eco-horror” speaks to our precarious and terrifying reality. Monsters take shape in many forms as we explore our house of horrors.

Throughout art history, terror has been represented in the mysterious and untamable presence of Mother Nature. Modernist notions of “the sublime” often inspired feelings of fear and dread in the face of nature’s beauty, most notably in the sublime landscape paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and William Turner.

In 1991, Damien Hirst assumed the role of God when he submerged a shark in a tank of formaldehyde. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living attempts to suspend a moment of terror—the petrified shark grins menacingly upon spectators—embodying the false and dangerous idea that humans can control nature. Hirst asserts dominance over one of the most feared animals, laughing in the face of Nature. Perhaps our modern era’s “sublime”-terror should be redefined by ceaseless colonization and the harrowing conditions of late capitalism. Dread resides in the banal as well as our narcissistically gluttonous systems of consumption. Drunk on greed and ego, we have mistaken ourselves for gods, when we are actually monsters.

“Hammer Projects: Max Hooper Schneider,” installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, Sept 21,2019–Feb 2, 2020; ©Max Hooper Schneider and courtesy of High Art, Paris and Maureen Paley, London, photo by Jeff McLane. Max Hooper Schneider (b. 1982, Los Angeles) imagines grotesque and ruinous landscapes of a human-centered world. He explores the complex interdependence between human and nonhuman life, between organic and artificial materials. Hooper Schneider’s mutations take shape in the form of terrariums and site-specific installations. For his large-scale installation at the Hammer Museum in 2019, Hooper Schneider imagined a dystopian junkyard in which organic and artificial materials coexist in a menacing entanglement. A plastic Costco size container of cheese puffs sits atop a mountain of cacti. A mangled shopping cart is engulfed by vegetation, its wheels reaching out as if gasping for air. Sneakers, toys and costume jewelry—once fleeting objects of desire—form a petrified litter of decay. Hooper Schneider’s defunct objects signify the headstones of late capitalism and their siting, nature’s ultimate triumph over humankind.

The inextricable bond between nature and culture, linked in a complex and tentacled web is considered in Hooper Schneider’s works. His background in landscape architecture and marine biology led him to challenge empirical scientific disciplines through art-making. He brings together concepts that have now become absurdly oppositional—nature and culture—as he examines survival on multiple levels; micro and macro, human and nonhuman. He asks, Who will inherit the earth? Will plastic relics of “human progress” haunt the planet when we finally perish?

Kiyan Williams, Reaching Towards Warmer Suns, 2020, Image credit: Mark DiConzi Kiyan Williams (b. 1990, Newark) is a multidisciplinary artist who frequently utilizes what has now become their signature medium: soil. The earth is where we bury our dead, grow our food—a material of decay, rebirth and growth. Soil contains so many histories; some perhaps lost forever, and others lying just beneath the surface, ready to emerge. Their work exists between the horrific and the cathartic.

Their large-scale sculpture Reaching Towards Warmer Suns (2020) is a group of 20 arms springing up from the earth and reaching towards the heavens, not unlike scenes of the dead rising from their graves found in countless horror movies. The hands make defiant fists, raise middle fingers, and gesture urgently, almost begging to be released from the earth of which they are composed and contained. These disembodied limbs are at once eerie, joyful and defiant; they recall the horrendous traumas of enslaved Africans, kidnapped and forced onto American soil, stripped of their identities, families and cultures. Standing more than six-feet tall, the arms are visceral, tragic and hopeful.

Kiyan Williams, Dirt Eater Installation view, In Practice: Other Objects, SculptureCenter, New York, 2019, Image Credit: Kyle Knodell In their video piece Dirt Eater (2019) Williams wears a steel patinated punishment mask—a device once forced onto enslaved people who practiced geophagy (dirt-eating). As they remove the mask from against their mouth, it pulls at their hair,—they wince. They lick, suck and kiss the dirt figure in front of them, expressing lust and disgust as they chew and swallow the thick brown paste. They smear what resembles both mud and feces across their mouth, eliciting a response of attraction-repulsion.

Williams’ work evokes the horrors and violence inflicted upon enslaved ancestors. This violence has solid roots in American soil, passed down through generations like a festering wound that refuses to heal. Williams’ haunting imagery confronts the colonialist atrocities embedded within the American landscape and upon which modern American capitalist society is built. Blood has seeped into the lithosphere and absorbed into the landscape. Williams’ work acts as a reminder of the violence embedded in the very ground we walk on, but also functions as a form of liberation from the traumatic shackles of the past.

Hugh Hayden, America, 2018. Sculpted mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) on plywood © Hugh Hayden. Courtesy Lisson Gallery New–York-based artist Hugh Hayden (b. 1983, Dallas) investigates our connection to the natural world, and the ways in which trees and organic materials carry traces of memory, survival and exploitation. For his 2018 show at Lisson Gallery in New York, Hayden’s carved objects of domesticity embodied the fantasy of the American Dream. A dining table, a picket fence, a crib and a stroller stand unusable. The wood’s smooth yet spiny skin seems threatening. What should carry feelings of comfort and safety instead summons danger and fear, suggesting the violent price of the American Dream. Hayden sharply questions who is provided the opportunity to attain ownership and safety in America. His large-scale installation titled “Hedges,” exhibited at The Shed in New York in 2019, depicts an archetypal American home. Branches jut out ferociously from the pores of the wooden frame, alluding to the unruliness of nature and piercing the surrounding space. Throughout his work, Hayden uses environmental issues and organic materials to speak about his personal experience as a Black man in America.

Hayden exposes our complex interactions with the natural environment and the ways in which systems of oppression are tangled up in history, politics, economics and just about every facet of life. He explores multi-layered, multi-temporal, multi-species ecologies. America remains haunted by racist systems that condition and perpetuate the endless exploitation of bodies, land and resources. We exist in a constant struggle to respond to and define our relationship with the environment and each other.

As our collective home continues to perish, we might ask: who lives and who dies? What kind of radical transformation will enable cooperation and collaboration over dominance and control? A collective exorcism? Can we face our demons? How can the horrors of our reality help develop strategies of survival (for humans and nonhumans alike)? Until then, we remain afraid, very afraid.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Leticia Maldonado

Bermudez ProjectsNeon is a medium that has been used over time to beckon, and Leticia Maldonado’s work viewed through the large glass windows of Bermudez Projects in Cypress Park does exactly that. Maldonado’s “Autonoetic” is a collection of mixed media that blends delicately thin bent neon with meticulously placed glass and other materials

Leticia Maldonado, Highland Park, CA, 2021. 5mm and 6mm glass clear and red glass, argon/mercury, rhinestones, organza, chiffon, faille, velvet ribbon, custom silicone insulators, and Plexiglass The natural world is clearly an inspiration for Maldonado. Three of the pieces are figures of black birds, their feathers made of out layered glass, with different elements fashioned out of neon. Another set of three in the exhibit display flowers bent out of different colored neon. Paradise, NV and Sullivan’s Island, NC are representative of dried flowers tenderly left hanging upside down in someone’s home, while Highland Park, CA looks like a branch of hot pink bougainvillea, often seen in the namesake neighborhood, meandering sideways across the wall.

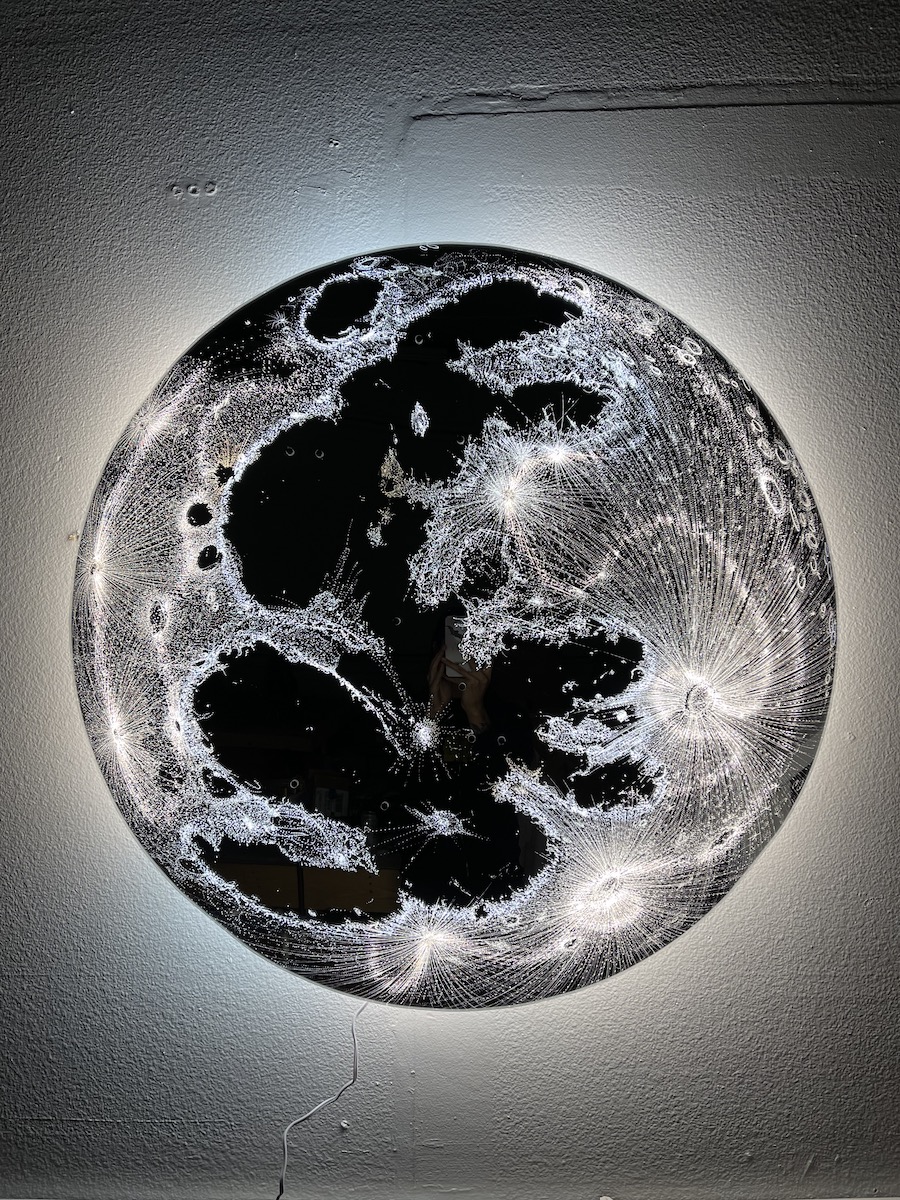

Leticia Maldonado, El Conejo, 2021. Hand-etched silver-mirrored Plexiglass, 8mm 6500 white neon tubing, 10mm 3500, white neon tubing, and argon/mercury These two sets are bookended by stand-alone works that are arguably the most compelling pieces in the show. El Conejo is a large round, etched mirror with extremely fine white neon that splashes across the mirror; it appears like the world viewed from above at night, the sprawling lights connecting cities and countries. The work is abstract and invites viewers to peer not only into it, but into themselves. Just a Moment Let Me Get My Things is the last piece in the show, and is a mixed media work of a vintage travel trunk open for the viewer to see. Inside it lies a trumpet and playing card made out of red neon, along with dried flowers and organza and rhinestone spiderwebs—motifs that link the piece to the rest of the show. This piece is like a still life painting come to life, and the play between ready-made objects and elements made out of neon is perhaps a glimpse into a new direction that Maldonado is heading.

Leticia Maldonado: Autonoetic

Bermudez Projects

July 10 – August 28, 2021

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Group Exhibition “Above & Below”Fans of Los Angeles’ Craft Contemporary museum will enjoy Above & Below at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. The exhibition features twelve artists working in textile art, ranging from ethnic craft traditions to the wildly unconventional.

The show marks the Los Angeles debuts of Madame Moreau and Yveline Tropéa. Moreau anchors the traditional end of craft in the exhibition with Henry Christoph flag, a beaded ceremonial vodou banner depicting Haiti’s revolutionary war hero and king. Tropéa’s canvases too are covered in beading, illustrating abstracted people and creatures that suggest folklore influences. The French artist lives part-time in Burkina Faso where she has been influenced by Yoruba beading, and where she hires and trains women–disenfranchised kidnapping survivors of Boko Haram–as beaders. Similarly, Gil Yefman felted a bedspread size wall hanging in the show with Kuchinate, a craft collective of African women refugees in Israel.

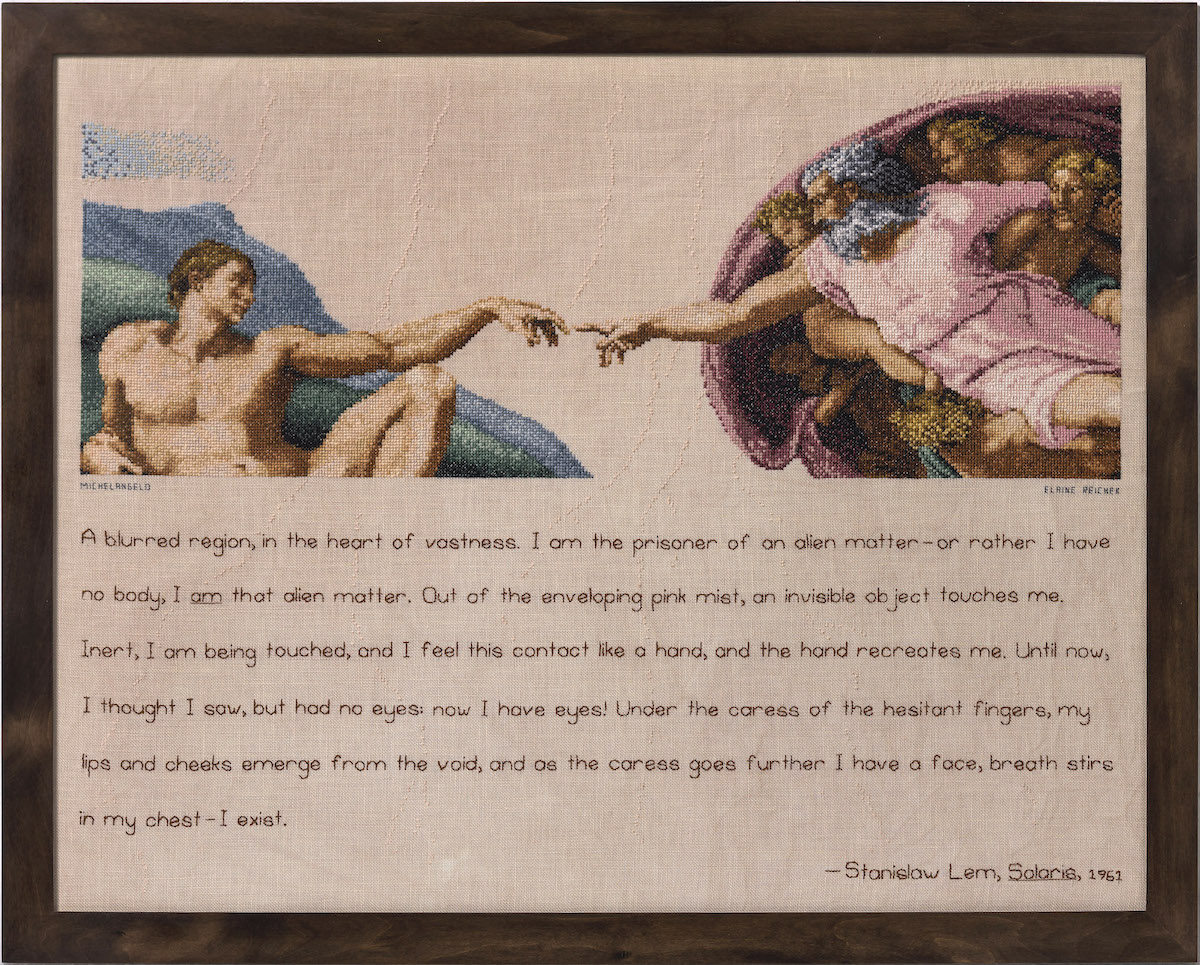

Madame Moreau, Henry Christoph Flag, c. 2020. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo by Gene Ogami. Textile art has a long history of dovetailing with feminism, placing value in traditional “women’s work,” as exemplified by Elaine Reichek’s Sampler (A blurred region). Sabrina Gschwandtner likewise draws on this history to pay tribute to early motion picture film editors, largely women whose names are forgotten. Her Hands at Work (For Pat Ferrero) Diptych consists of 16mm film strips sewn into two quilt-like patterns mounted on lightboxes.

The current textile art renaissance is also dovetailing with the LGBTQ movement. Transgender artist Max Colby’s assemblages burst with camp, sprouting phallic shapes covered in beads, plastic flowers and Christmas ornaments. These works find their closest kin in the show in a beaded and studded punching bag, Cloudbuster, by Jeffrey Gibson, a queer Cherokee Choctaw artist. Conical metal beads known as jingles–which adorn the dress of pow-wow dancers–cover the lower half of Cloudbuster, tempting visitors to punch it and make it rain, at least sonically.

Jeffrey Gibson, Cloudbuster, 2013. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo by Peter Mauney. As well as beading, weaving is a prominent technique in Above & Below, with interpretations by Terri Friedman, Din Q. Lê, Anina Major, James Richards, and Frances Trombly. Friedman’s wall-sized tapestries particularly push the boundaries of weaving with riotous combinations of colors, textures, negative space, and hidden messages. One aptly says, “Alive.”

Above & Below

June 15-August 28, 2021

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Ontario Museum Biennial

Ontario Museum of History and ArtThe act of self-disclosure is an intentional revelation of one’s thoughts, emotions, and feelings to another individual; it is part confession and part declaration. The 11th Biennial Ontario Open Art Exhibition at the Ontario Museum of History and Art was an aesthetic self-revelation by established and emerging contemporary artists. The widely varied works were both two and three-dimensional and employed a variety of media and subject matter, from textile to photography to clay and metal. Contemporary portraiture kept company with cat paintings and wide-angle photography was side-by-side with optical abstraction. With Kathy Ervin, Professor in the Department of Theatre Arts at Cal State San Bernardino as the juror, this show is truly an example of a collective community voice.

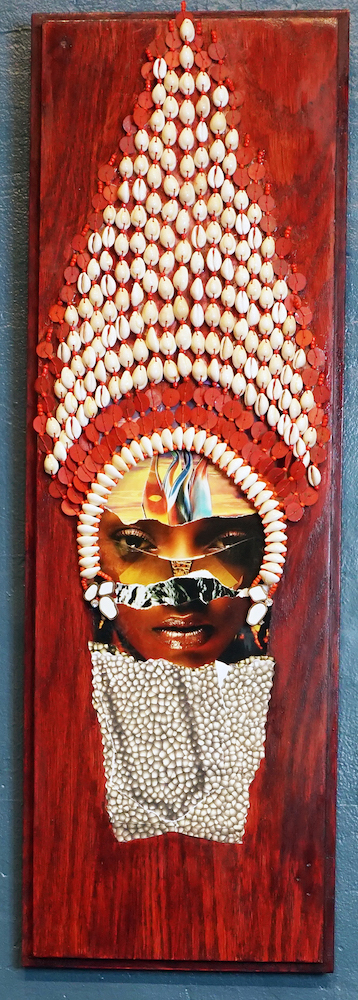

Patricia Jessup-Woodlin, Ancestral Reclamation, 2020 Of particular interest is Ancestral Reclamation (2020), a photomontage/assemblage by Dr. Patricia Jessup-Woodlin, a retired art education professor. On a narrow wooden panel, a portrait of a woman of color is elegantly rendered in fragments of torn collage. She is crowned with a pyramid of ascending cowrie shells and her mahogany eyes are proudly confrontational and penetrating. This work is suggestive of the recent Black Panther film and the woman portrayed—a fragmented portrait of all African women—appears to be reimagining a Black future. It is no coincidence that using cowrie shells extends the meaning of this work’s title. In Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania dating back to the 14th century, cowrie shells served as currency for goods and services. Ultimately, these shells constituted power and were used by Africans for protection. The significance of this work is twofold. First, it resists erasure the glorious past before African enslavement. Second, it illustrates the message of Haile Gerima’s 1993 film, Sankofa; the lessons learned from past function as a roadmap for actualizing a powerful future.

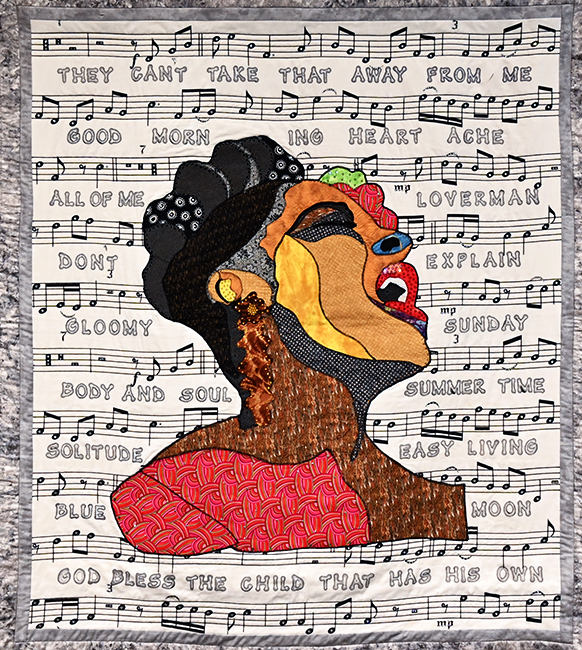

Lady Day’s Lyrics (2019) by Annie Toliver, an exhibition prizewinner, puts a fresh spin on the idea that relationships range from the toxic to transformative. In this portrait of Billie Holiday, rendered with fabric and ink embellishments, complementary hues jigsaw a profile. Holiday’s face is centered in the composition, floating above a background of sheet music that makes reading the titles of her greatest hits an irresistible pleasure.

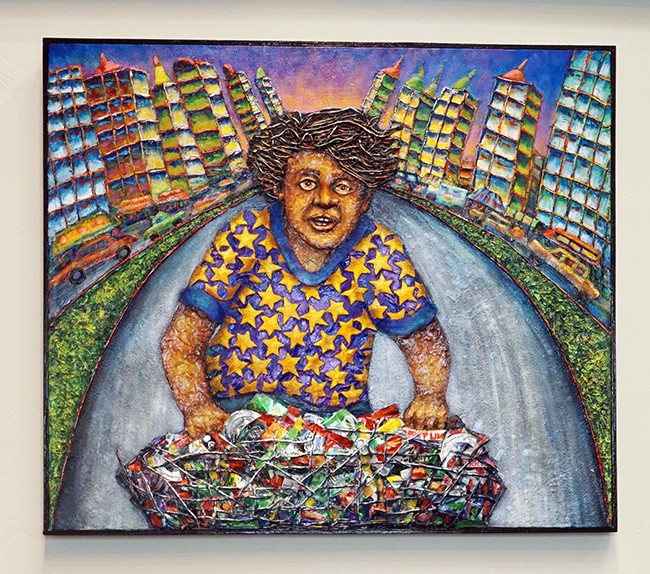

Rick Cummings, Aluminum Dreams, 2021 Rick Cummings captures a hurried desperation in his mixed media Aluminum Dreams (2021) where a woman is depicted pushing a shopping cart filled with aluminum cans. Additionally, her yellow star (five pointed, not six) designed shirt alludes to an exploitative, capitalist America limping along economically amid a push to reopen the country immediately after a global pandemic has ravaged the planet.

This exhibition offers a glance into a talented community of artists. Professionally trained or self-taught their willingness to reveal themselves creatively encourages a reciprocal viewer response—actions that foreshadow a change in one’s thinking, not only about art but about ourselves. In Parable of the Sower (1993) Octavia Butler expressed it best by writing “All that you touch You Change. All that you Change Changes you. The only lasting truth Is Change.”

11th Annual Biennial Open Art Exhibition

Ontario Museum of History and Art

225 S. Euclid Ave. Ontario, CA 91762

May 6-August 15, 2021

-

Duane Paul

“Speaking Tongues (The material of communication)” introduces Duane Paul’s considerable talent and ability in the artist’s first solo exhibition. The show’s 12 works (all 2013) are divided into three sections or “dialect clusters:” six works on paper, two free-standing sculptures and four wall reliefs. The dynamic exchange of visual dialogue among and between clusters is both provocative and revealing, centering on issues of texture, shape, size, color, line and volume.

Perhaps the works on paper could have been larger so that one might better appreciate their dense and richly worked surface textures. Their success is owed in part to 2-ply construction, revealing pockets of translucency that act as metaphors for unresolved fragments of childhood memories, juxtaposed with adult reflections, lessons and experiences. Paul introduces amoeba-like forms to these compositions, as visual anchors, focal points and enigmatic presences. The issues are of both a formal and personal nature.

Repetition signifies process, rhythm and progress. In Paul’s hands repetition and rhythm also become the tools for gathering a network of unresolved personal themes and challenges, offered up for resolution and/or transformation as revealed in the artist’s statement.

By repeatedly building up his sculpture’s surfaces, he employs a culture of “making and doing,” where the construction of the piece is as important as the final work itself. The repetitive process yields a form that physically resembles a thin, narrow seedpod, a rattle or elongated tongue. Their curvature is configured into a modified boomerang, and their layered construction mode is designed to expose layers of material information—levels of consciousness (similar to Mark Bradford’s “layered cutaways”), which eventually become visually unfamiliar and obscure. This is particularly so in Paul’s totemic piece; one example is a broken saddle in Humpty Dumpty’s Saddle Broke, which coincidently resembles an African headrest.

The mixed media wall reliefs exhibit Paul’s greatest strength as a painter and sculptor. Quite Rebellious, Stares Intently and Daddy Blows Smoke are two examples. Each piece offers a woven structure that allows for open-ended readings, of either coming into being as constructed (woven) or deconstructed (unwoven). Together the works balance motion and stillness in the most eloquent terms. They share the rhythmic turns and leaps found in Al Loving’s later works incorporating french curves and spirals. The reliefs’ impeccable workmanship recall the structured weavings of Martin Puryear’s craftsmen minimalist sculptures, with more painterly surface treatments, offering forms that are intentionally left ambiguous to the eye. As one observer noted, their polychromed surfaces echo the palette of Sam Gilliam’s early draped paintings. Tom Holland’s fiberglass 3-D paintings with physical strips attached to the painting’s surface also come to mind as a reference for Paul’s work. The tension created by the curvature in slats (made from a combination of various laminated materials, following the artist’s personal formulas) rivals the level of tension/drama found in Loren Madsen’s early “bend” pieces, created and fashioned from redwood slat and/or board back in the ’70s.

Paul’s exhibit is the result of the artist’s thinking-out-loud, in a much broader historical context that goes beyond generations, creating the profound conversation between the works engaged in “Speaking Tongues.”