Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Los Angeles Philharmonic

-

“Some Make You Sing….” (Part 2 of 3)

Something kind of hit me today

I looked at you and wondered if you saw things my way

. . .

We’re taking it hard all the time

Why don’t we pass it by?

David Bowie, “We Are the Dead”

from Diamond Dogs, 1974

The first part of this post promised a superfecta; and I’m not sure it’s possible to live up to that, if for no other reason than simply the difficulty of making any kind of conclusive judgment on the kinds of shows I’m looking at in the space of a few hours spread out over 30 square miles. Sure, there are a few (e.g., the shows already covered in the first part of this post) – and even there, it would be absurd to say that my opinion might not be revised over repeated viewings. This is why we revisit shows in the first place. Or why we return frequently to favorite works in museums. Our first impressions are never our last; we bring something fresh to each viewing and take away something new.

Which is why I’ll be going back – not just to the shows I’m about to mention, but to the shows covered in (and some of those omitted from) the last post. I wanted to linger at George Legrady’s show at Edward Cella; and certainly his multi-layered, multi-faceted lenticular panels invited it; but couldn’t have spent more than 15 minutes with them. Memory is mined and manipulated in Legrady’s work, no less than Barnette’s, and far more explicitly. It also moves in both actual and remembered space and time for both the viewer and (presumably) the artist himself – which apparently related directly to the two-channel interactive animation piece Legrady is fascinated by the collage/montage of time and memory; the contemporary (or simply invented) foreground and (remembered or recovered) background of memory. The groundwork for the work was apparently laid with the discovery of a collection of family photographs taken mostly in eastern Europe (between Hungary, Romania and Transylvnia); and the lenticular work here apparently draws from photos of a Transylvanian picnic outing. You can see immediately how the lenticular work might lead to animation studies. The lenticular prints have their own quality of animation (albeit partially supplied by the viewer), but more important is the inherent fascination of the underlying photographic material and the overlaid imagery. I had to wonder how the animation would amplify that experience.

As I occasionally do in these instances, I had a look at the press release which set out Legrady’s aims more or less straightforwardly; also noting his “contributions to the computational arts,” which sounded like something more applicable to tax accounting – but maybe there’s a layer I’m missing.

It made for a striking transition to go from Chris Ballantyne’s show at Zevitas Marcus (next door to Edward Cella) that pursued a number of architectural and geometric themes and motives (and natural, too) to Toba Khedoori, whose past work has exploited both architectural and natural motives in her draughtsman-like explorations of existential and quasi-serialist geometries, at Regen Projects. Settting aside one striped painting that seemed almost literally a serialist work, it was quite different from what I expected. Here, only two paintings – seemingly tilted, eliding views of polished ceramic tiling more or less filling their respective canvases, one presented more frontally than its angled mate, bore distinct relation to that past work. Here, even meticulously rendered branches and leaves (in a completely white space) seemed well removed and on another plane completely from even previous naturalistic studies. Rather, the emphasis seemed to be a Fontana-esque contrast between the delineated plane and the absolute void – physicality and nullity.

From this kind of ‘naturalistic’ yet slightly ethereal art concrète, it was not much of a leap to the equally ethereal yet silken domain of Lita Albuquerque, at the Kohn Gallery. Albuquerque is well known for (frequently site-specific) work that bears on the body’s relationship to both the earth and cosmos; and surrounded by gold and silver discs in the main gallery, each inset within dense fields of rich, vibratile color that evoked both terrestrial and celestial qualities – purples both boreal and nebular, luminous sapphire blues that were both atmospheric and referenced the cosmic infinitude – the viewer felt suspended in a lunar ceremony. The jewel-like intensity of the color owes something to Japanese Enogu technique (or so the press release informed us – with the colors laid over layers of black and white); which may have something to do with the ceremonial aspect of the show. It was impossible not to be reminded of Japanese screen and silk painting.

: : :

That little ellipsis marks the approximate moment I broke off to surrender to the viral mischief that had besieged me. Part 1 went up without too many digital hitches – along with a nod to Bowie, whose funeral pall I was involuntarily sharing in body as well as spirit, as I succumbed to what felt like a not-so-mild bout of bubonic plague. That week-end was as notable sonically as it was visually; though, as with the George Legrady lenticulars, everything seemed strewn beneath leaves, branches, lakes and forest thickets. Even before the evening’s openings, I had the great fortune of hearing most of the Met broadcast of the closing performance of this season’s (David McVicar) production of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena – and possibly one of the greatest performances of the title role I’ve ever heard. In Sondra Radvanovsky’s performance, the dazzling vocal pyrotechnics (the role has an intimidating range from lowest to highest register) were matched by an incomparably supple and dramatically insightful handling of the role’s emotional complexity. Donizetti’s Bolena is every inch the queen she actually was, but also vulnerable and manifestly conflicted. Radvanovsky gave full scope to that emotional breadth and conflict in a dazzling coloratura performance that seemed to move inexorably from a high-strung regal poise to passion and indignation, from romance and resignation to tragic elegy – eclipsing possibly every other performance I’ve heard in the role, including Beverly Sills. She was well paired with her various foes and foils, including the incomparable Jamie Barton in the role of Giovanna (Jane Seymour), Ildar Abdrazakov as Enrico (Henry VIII) and Stephen Costello. There were so many great moments, I couldn’t begin to enumerate them all; but I will say Radvanovsky’s aria at the close of the first act (paralleling Abdrazakov’s responsive aria) was ineffably heart-rending.

I guess some people would say I was ready to get carried away on the first horse I mounted. But there’s really nothing quite as moving as the human voice. The following day, Emmanuel Ax brought an equally, agelessly supple technique back to Disney Hall for a performance of the Franck Symphonic Variations with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. (The Chopin C# minor nocturne he encored with wasn’t bad either.) The Pierre Boulez Mémoriale for flute and octet had actually been my selected ‘A’ side for the afternoon. Its timing – only days after Boulez’s death at 90 in Baden-Baden – was purely coincidental; but its original spirit made an appropriate memorial to its composer – and the soloist, Denis Bouriakov, and guest conductor Daniel Harding captured that spirit beautifully. Another uncanny coincidence was Harding’s expressive and slightly ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style – strikingly reminiscent of Boulez’s own distinctive ‘contrapuntal’ conducting style, though, unlike Boulez, Harding used a baton through all but the Mémoriale. Hard to say what Boulez would have made of the unbridled lyric romanticism of Schumann’s 2nd C major Symphony; but Harding and the Phil made something gorgeously soaring of it. The third movement C minor Adagio was possibly the most beautiful rendition of that movement I’ve ever heard.

Finally – Bowie…. [Continued Part 3]

-

I’m A Stranger Here Myself: Soundtracks for scary screens and scarred landscapes

The center of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Friday evening program was a shimmering pulsation of musical color, both harmonic and timbral, in a field of black and white. Both Susan Graham’s rendering of a suite of Kurt Weill songs and Esa-Pekka Salonen’s own suite for full orchestra, Foreign Bodies, also conveyed a sense of the almost schizophrenic tension that carried through the entire program—the alien presence within the cozily familiar, the vernacular within the poetic, excitation mingled with anticipated regret.

There were certainly ‘black-and-white’ notes here, too—the raffish/Runyonesque (albeit German) gangster story behind “The Song of the Big Shot” (‘hard nut’ in the German expression—with lyrics by Brecht), songs from Lady In the Dark (with lyrics by Ira Gershwin) that evoked a black-and-white Manhattan of the 1930s and 1940. But there were amber hues, too (September Song), the syncopation of “I’m A Stranger Here Myself,” and the blues-y color of “The Saga of Jenny.” The songs were a kind of time capsule, but a richly reverberant one; and Graham was clearly enjoying this meander through a slice of Broadway history that somehow bridged chasms of emotion and time.

In its broad orchestral plan, Salonen’s Foreign Bodies offered a foretaste of the Varèse Amériques that would close the evening. (The percussion requirements for both compositions were both daunting and strikingly distinct—e.g., Thai nipple gongs in the Salonen; sleigh bells and, uh, ‘lion’s roar’ in the Varèse.) Chimes and percussion led off, with trumpets and broad brass lines giving way to more articulated figures in woodwinds and vibes. Violin tremolos lead into massed string episodes which segue back to flute and winds.

You practically felt the ‘winds,’ as if Salonen were waving his conductor’s baton over a field of wind-swept wheat, with parallel chromatic/harmonic changes registered between strings and horns. The music swung between a farandole-like figure in the horns and ethereal but arresting foreground lines in the winds and strings. The third movement (“Dance”) seemed to evolve these motives rhythmically and metrically with horns variously competing and underscoring other orchestral textures, some of which only faintly registered while others resounded with near ferocity.

There were textural (and certainly percussive) parallels between the Salonen and the single-movement Amériques of Edgard Varèse, but the works could otherwise have hardly been more different. Where Salonen’s work builds a kind of machinery of dance, Varèse builds what can legitimately be called a soundscape, a prototype for music (including electronica, film scores and ‘sound art’) being composed today. The score (there we go—no?) begins almost insinuatingly—a quiet line that might be nothing more than a meditation. (It is, for all its crashing dissonances, a meditative work.) But it moves efficiently forward, in crescendoing, ascending lines in trumpets and percussion, before settling again in the flutes and woodwinds.

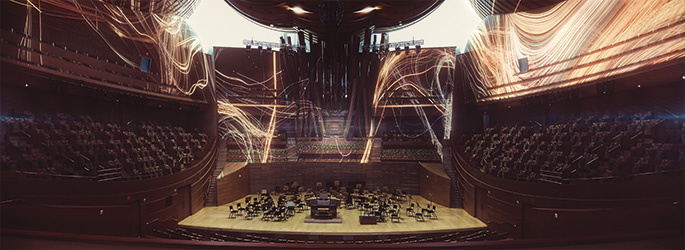

We were primed for what began to crescendo physically around us in the hall (in a sense delivering the impact we felt missing from the Herrmann suite from the Alfred Hitchcock film, Psycho, that opened the evening’s program). It would have been one thing to construct a film or video for the two-dimensional screen; but what the video artist, Refik Anadol, essayed here was a visual interpretation of the architecture of the music onto the architecture of Disney Hall itself. This was not a literal three-dimensional mapping of the score; and the effects here were variably two- and three-dimensional; but they did succeed in paralleling, to some extent magnifying it, enveloping the audience in this echt-urban soundscape. The video passes (with the score) through swirls and eruptions of motes, molecule-like chains, fibres, sand or snow into fluorescing grid-like formations, in turn giving way to prismatic geometries, evolving and devolving like chambered shells and coral reefs. In certain passages, it made me think of some of the imploding urban blocks in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film, Inception. The machinery and mechanicals gradually morphed back into the comets and shooting stars with which it began. Throughout, there were sly references to the physical production of the music itself (e.g., the conductor’s silhouetted moving figure).

It can be argued whether or not these elements—Anadol’s exploding and imploding blocks–adequately served the ‘blocks’ of the Varèse score, which tumble and pour at us episodically with spare (if any) musical development or elaboration. (There are ‘bits’ here reminiscent of everything from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to Bruckner to Gershwin and jazz and sirens and jackhammers.) But as ‘music drama’—sheer sight-and-sound spectacle—I thought it remarkably effective. What was most telling was the contrast with the music that began the program. The score for Psycho is one of the most superb Bernard Herrmann ever wrote; and was superbly played by the Philharmonic’s strings on this particular evening. Even so, you felt its impact diminished by the film’s absence. That was part of the essence of its collaborative genius (and contrary to the ridiculous program notes, Psycho—shot for shot one of the greatest pictures ever made—would never have been “relegated to footnote status”): Hitchcock and Herrmann each ‘signed’ the other’s work.

It can be argued whether or not these elements—Anadol’s exploding and imploding blocks–adequately served the ‘blocks’ of the Varèse score, which tumble and pour at us episodically with spare (if any) musical development or elaboration. (There are ‘bits’ here reminiscent of everything from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to Bruckner to Gershwin and jazz and sirens and jackhammers.) But as ‘music drama’—sheer sight-and-sound spectacle—I thought it remarkably effective. What was most telling was the contrast with the music that began the program. The score for Psycho is one of the most superb Bernard Herrmann ever wrote; and was superbly played by the Philharmonic’s strings on this particular evening. Even so, you felt its impact diminished by the film’s absence. That was part of the essence of its collaborative genius (and contrary to the ridiculous program notes, Psycho—shot for shot one of the greatest pictures ever made—would never have been “relegated to footnote status”): Hitchcock and Herrmann each ‘signed’ the other’s work. -

Some Enchanted Evening – Così fan tutte

Mozart, like other great artists before and since, offers us a topological mirror in which to test and tease our perspectives on the universe and our fragile foothold in it. The evocative power of his greatest work is a sublime irony, felt all the more acutely as the civilization in which it blossomed has devolved into a death star. You feel it most poignantly in moments like the E major trio at the end of the second scene of Così fan tutte, “Soave sia il vento…. Ed ogni elemento benigno rispona ai nostri desir.” (“May the winds be gentle…. And every element respond benignly to our wishes.”), where the voices of the sisters, Fiordiligi and Dorabella, and the ‘philosopher’ buffo classico, Don Alfonso, rise and sway over the rolling thirds.

I have had the opportunity to hear and/or see many productions of Così over the last few decades – staged, filmed, radio broadcast, and recorded; but few have matched the symbolic power, wit and elegance of last night’s Los Angeles Philharmonic production (by Christopher Alden, in collaboration with Zaha Hadid, with costumes by Hussein Chalayan) at Disney Hall, the third in the Philharmonic’s three-year Mozart/Da Ponte trilogy project. Although the vocal performances came nowhere close to eclipsing the very best (Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Fleming, von Otter, Lott, and some of the gifted baritones that have sung Alfonso and Guglielmo, set a very high bar), the principals – all well-experienced in the roles and Mozart opera generally – were all superb; and Rod Gilfry (Don Alfonso), Philippe Sly (Guglielmo), and Rosemary Joshua (Despina) were particularly outstanding. It didn’t hurt that Miah Persson (Fiordiligi) and Roxana Constantinescu (Dorabella) are both gorgeous and carried the Chalayan costumes beautifully. The Philharmonic was in gorgeous voice, too (even with Maestro Dudamel and Bradley Moore, on harpisichord continuo, dragooned into the drama by Alfonso’s stage antics – they coped beautifully).

It’s hard to say whether it’s an eye-of-the-hurricane notion of calm amid chaos underlying the concept of the Alden-Hadid production (Hadid’s set design was supervised by Saffet Kaya Bekiroglu), or a more abstracted notion of radical contingency in which personal orbits are alternately at odd tangents with one another or in seemingly parallel universes. (A ‘circling the drain’ metaphor occurred to me, too.) The torqued ellipsoid spiral in what looked (under the shifting lights) at one moment like concrete, and like some pearlescent laminate at another, owed something (I thought) to Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (the Toruses, too), but also to the torqued and shifting planes of Gehry’s Disney Hall itself – the whole of it seeming to echo those ‘gentle winds’ – and the Philharmonic’s gorgeous woodwinds, rarely more beautifully displayed. Whether the eye of a hurricane, an umbilicus tethering its hapless lovers, or a death spiral, the set (which spilled out into the orchestral space with yet another elliptical curve pooling flat onto the stage) beautifully supported the deceptively cynical Da Ponte farce that Mozart’s music somehow manages to make transcendently magical.

Alden moves the characters almost like tokens or mathematical markers in a table game. They seem to rotate around the curving set, as if by some remote control as much as under their own power, emerging or disappearing at one end of the spiral or another as if in a labyrinth. Hewing closer to an ‘umbilicus’ scheme, Chalayan dresses the lovers in what look like summer camp clothes. The men in shorts and butter yellow and blue chambray shirts, the women in schoolgirl pleated gray and white skirts and chalky Egyptian blue and salmon camp shirts. Don Alfonso and Despina, by contrast, are all business – stylishly booted and dressed in squarish black jacket and pants. Alfonso and Despina are always the hidden magic in this show and Alden (facilitated by Chalayan’s costuming) underscores this aspect, making of Alfonso a dissolutely capricious Oberon, and Despina into an extremely capable Puck. They’re also a lot less hidden: Alfonso/Gilfry commands every part of the stage (including a part of Dudamel’s podium at a couple points, breaking an interior fourth wall) and a seat just over the curving wall of the set (where he props up his legs and sprawls across a raised pedestal or console, munching from a bucket of popcorn); Despina/Joshua commands the spotlit center stage for her lecture on the fickleness of men and the pointlessness of fidelity, “In uomini…” It’s not surprising, given their blistering vocal and acting talents, that they practically steal the show. (I’ve always thought the character’s name is far from coincidental – between sea and (under)world; of the spine/undercarriage and the world of the dead.) It should be emphasized, though, that all of the singers move with exceptional grace – and on steeply raked and banked surfaces that can’t be easy to negotiate, especially in boots or heels. I almost wonder if Alden had some assistance choreographing the show.

The costumes morph as the opera progresses – ‘summer camp’ clothes giving way to ‘trench (warfare?) and frock coats’; and the set itself morphing and even ‘respiring’ by way of Adam Silverman’s genius chiaroscuro play of light and shadow moving across the set like storm clouds. (Many a museum show might profit from this design magic.) I think there may be some hydraulics beneath those embankments, too; but the rising and falling curves did not distract from the music. For all the Minimalist, post-Beckett look of the production, it did not (eat your heart out, Robert Wilson) feel minimalist. Set, choreography and overall production supported an idea of continuous curvilinear, rotational movement: the tricks space play on our minds and the circuitous tricks our minds and perceptions play on us. In this rendering of Da Ponte’s libretto, betrayal is simply one point on fidelity’s funhouse slide. (“So wanton, light and false, my love, are you, / I am most faithless when I most am true,” was the way St. Vincent Millay put it.)

The universe is not a particularly hospitable place, and we almost take solace in its sublime indifference to human fates. (“A philosopher laughs while others are weeping.” The Phil’s translation of (I think) “Quel che suole altrui far piangere fia per lui cagion di riso….”) After the solace and exhilaration of Friday evening’s Philharmonic performance, though, I couldn’t help thinking that a universe bereft of Mozart might be an order of cosmic betrayal even the universe might not be ready to endure.