Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: literature

-

Publication in the Age of Negation, Part IV

Wasted WordsOne sends out this precious, all too precious, closely guarded work to complete strangers: they might initially take an interest, but after being presented with the entire manuscript, they can’t be bothered to get back to you at all, not even with a brief cordial rejection note.

It makes one doubt the quality of the work.

I started to re-read the work that has been the cause of all this unpleasantness again, and after a few pages began to see it in a harsher light: It was too repetitive, too relentless, too tight.

Since I officially finished the novel, over a year ago, I had spent a lot of time tinkering with it. Every time I opened the document, I would be confronted with something that needed to be changed, and then something else, and hours on end would be spent making minor adjustments, many of which didn’t need to be made. These endless finishing touches were draining the life out of the work, and I wanted to avoid the airless quality that I disliked so much when I encountered it elsewhere. I needed to leave it alone. But with no end in sight regarding publication, it was difficult to resist fiddling around with it.

It pained me to consider that I had prioritized this finely-honed ego-driven mess over everything else. All the time I’d put into constructing paragraphs, sculpting sentences, and leaving no synonym unturned in exhaustive searches for le mot juste—all that manic manicuring couldn’t turn out to have been in vain. What would be useful would be the services of an editor invested enough in the work to insist on my removing about a quarter of it, with whom I would be delighted to collaborate, preferably with the promise of publication.

Why this craving to be published by a ‘reputable’ imprint? Any self-respecting author should ignore the major outlets as an act of principle, and I would normally adhere to that credo, as I had done until now, not that I had any choice in the matter, but it was my stubborn belief that the work in question, by its nature, required such validation. Were it to be published by a micro-press, the sentiments contained therein would appear even pettier than they already were. Inevitably, I would end up settling for less: that knowledge was built in.

Vincent van Gogh, “Still Life with Three Books,” 1887. I walked out into the refreshingly cool evening air, straight into the path of a neighbor, Mike Eupole, who was taking a walk.

He didn’t seem particularly displeased to see me and obligingly took out his earbuds when I hailed him.

“I was just thinking about you yesterday,” I said. “I was reading your blurb on the back of Zander Valvitcore’s novel. What did you really think of it? Be honest.”

“I liked it,” said Mike unconvincingly. “It was a good story. It had some nice touches.”

“But he can’t write, can he? He can’t construct a complete sentence. It’s nice that he’s trying, and you can see the effort he’s putting into it, but he can’t quite manage it. He’s a nice guy though. I know him vaguely.”

Mike smiled and nodded noncommittally.

“This sort of thing really shouldn’t be encouraged,” I continued. I hadn’t been outside all day and after sitting at my desk—and in my green armchair, and on the sofa, and lying on my bed—brooding ruinously for hours on end about various slights and injustices, without speaking to a single person, I now found myself in an unusually garrulous mood, needing to let off steam. “I mean, what’s with this Alt-lit crap? Do we really need an alternative to literature?”

Mike laughed. He didn’t write Alt-lit, but he had supported it by bestowing a complimentary blurb on Valvitcore’s execrable novel, Wasted, that was getting a lot of undeserved attention owing to the author’s busy presence on social media, networking abilities, aggressive affiliation with a pointless and transitory new literary trend, and the book’s calculatedly attention-grabbing cover design.

“It’s just an excuse for people who aren’t interested in writing properly,” I continued, warming with malice to the subject. “It allows illiterates to make their contribution; it allows people who want to call themselves writers to commit acts of unacceptable degradation on the English language.”

“I guess it’s a bit like punk rock,” said Mike: “people who can’t play an instrument forming bands.” From his more elevated position as an established writer, he could afford to be more forgiving, or indifferent.

“Exactly,” I said, “and it has a snowball effect in that it encourages people to get involved in something they have no experience in or aptitude for. But it’s a lot more fun listening to somebody with loads of youthful energy bashing out three chords than reading somebody that can’t construct a sentence struggling to express themselves.”

“It’s an internet phenomenon,” said Mike.

“Maybe I’m missing the point,” I said. “But in 20… or 10… or five years’ time, will any of these epoch-defining works of Alt-lit, autofiction and so-called transgressive literature stand the test of time? You don’t need to be aligning yourself with this crap.”

“What are you up to?” said Mike, changing the subject.

“As a matter of fact, I’m trying to get a novel published,” I said.

“That’s great,” said Mike, suddenly sounding vaguely enthusiastic, and probably hoping to get me off his back.

“Well, it would be great, if I could get it published. Now I’m writing a series of pieces chronicling my various frustrating interactions with publishers and agents. Stay there. This won’t take 30 seconds…”

I went back upstairs as quickly as possible given my debilitated condition and picked up my car keys. Conveniently enough, my car was parked directly in front of my apartment. I opened the trunk and handed Mike the latest issue of Artillery.

“Here’s the first installment of the series. I can’t stop churning this stuff out. No amount of rejection can stop me. Sickening, isn’t it?”

“I know how it is,” said Mike, with a dry smile. Yes, he knew. But he was also assured of publication, having had a string of novels published by a major house.

“At least you have an excuse,” I said. “You know that your work is going to see the light of day. That must be nice.”

“I guess so,” he said, and gave a nonchalant shrug. He was out of the trenches but perhaps he had moved on to another, more advanced sphere of struggling. Each of us had our own battles.

“What’s your agent situation?” I asked him, and why not? It wasn’t every evening that I walked outside and immediately encountered a widely published neighbor. There could be no harm in asking.

“I have one,” said Mike with deepening indifference.

“Well, they seem to have done good by you,” I said, and elicited another good-natured but apathetic shrug.

“You’re welcome to contact her,” said Mike, kindly saving me the trouble of asking.

“Most kind. You really wouldn’t mind? Because I will.”

I reopened the trunk of my car and handed over the latest issue of the Santa Monica Review, which contained a short story of mine. “Read this, so you can be assured your agent’s time isn’t being completely wasted,” I said.

Mike probably wouldn’t read it. He was a helpful sort, but, I suspected, fairly indiscriminately helpful. It didn’t matter. He had provided me with the name of his agent, and I would contact them.

I walked down to Sunset. There was a new restaurant down there that apparently made a great hamburger. But on the strength of their weak name and the nature of the clientele observable at the outdoor dining section, I had vowed never to grace their threshold. However, they now had a take-out window open for business, and I ordered a hamburger to go.

“We don’t take cash here.”

“I’m sorry.”

The tiny young woman in the window repeated the statement.

“You’re joking…” I began to splutter.

“I just work here,” she said, and had to repeat this statement after another abortive eruption of spluttering indignation.

“For fuck’s sakes!… I know, it’s not your fault. Is there anybody here in a position of more authority that I can yell at?!”

There wasn’t. I walked off fuming about this elitist, self-defeating practice that discriminated against the poor, and those of us with bad credit. It wasn’t the only local dining establishment to have adopted this policy, which was illegal in New York. A cashless society: what was the world coming to?

Trophime Bigot, “A Doctor Examining Urine,” c. 17th century. I went ahead and contacted Mike Eupole’s agent, Susan Fumus Blear:

Mike Eupole might have warned you that I’d be in touch, as he was kind enough to pass your contact info along.

Yes, he probably had warned her. He had probably apologized in advance for the inconvenience of having to deal with me and told her not to feel under any such obligation.

The novel in question does not examine issues of gender, race, class or identity. However, encouraged by some positive recent developments (an outright lie) I’m renewing my efforts to get it published by a reputable imprint; at the very least, a good independent press with distribution. I am deluded enough to believe that the novel possesses sales potential… ad bloody nauseam…

The weeks passed by.

An encouraging rejection letter, if such a thing can be said to exist, arrived from the pen of Stella Loryn. It was evident that she, and her assistants, had actually read the thing, which was a new experience for me:

“I have shared your novel with several readers and each had great things to say about the quality of writing, characterization and humor: qualities that are intensified when delivered in such a unique and darkly humorous style as yours. The voice reminded me a little of Mitchell Wellbeck. I greatly enjoyed reading it, not least because you have managed to write unusually well about writing itself, which is one of the hardest things to write about.

However, as you are probably aware, the publishing industry is still impacted by several years of compromised business, and this has resulted in many established authors losing out, as well as debut writers. Even before the pandemic, dark and ambitious literary fiction was a tough sell, and with its effects still being felt, it has become even harder.

I have no doubt that there is a readership that will love your novel, and I would strongly advise you to continue submitting to other agents.

Again, we wish all the best for you and thank you for sharing this manuscript with us…”

There was a lot of sharing going on in the world these days.

More time passed by, as I knew it would, and I gave up, as I knew I would, on sending the novel out. The fear that I wouldn’t put the required effort into getting it published had quickly materialized. After years—decades—of self-thwarting procrastination, I had finally delivered of myself, but my efforts had failed to rouse much interest in the few incompatible parties I’d trafficked with. The sense of futility engendered by these dealings with the literary establishment hung over other potential undertakings. There didn’t seem to be much point to writing anymore.

This is Part III of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II and Part III.

-

POEMS

“Poem April 3” and “Do It Again”Poem April 3

The language you are now reading

will be born tomorrow morning

when the sun that resides in each

one of us turns back into music.

You and I will be in transit, as usual,

rolling along the new roads,

practicing our stories in case

we’re asked about our adversaries.

The language? Rinse your hands

in its shapes, lift up your eyes,

accept its disobedience and its

habit of separating the human body

from the lilacs it desires. And of burning

any habit into the present moment.

—James Cushing

Do It Again

A blissful grind along a powdery track,

a delivery system into a black hole.

The destination lies straight ahead, wrapped

in warped warmth, outweighing desire

and assuming control. This sinister sweetness

nullifies the usual consolations and makes light

of agency, so that you’ll go to any length

to make weakness a strength; and when life

becomes too stark again, and you want

to turn the lights down low again,

you’ll always go that extra mile

to let your willpower crumble

into a flaky white pile.

—John Tottenham

-

Ways of Reading

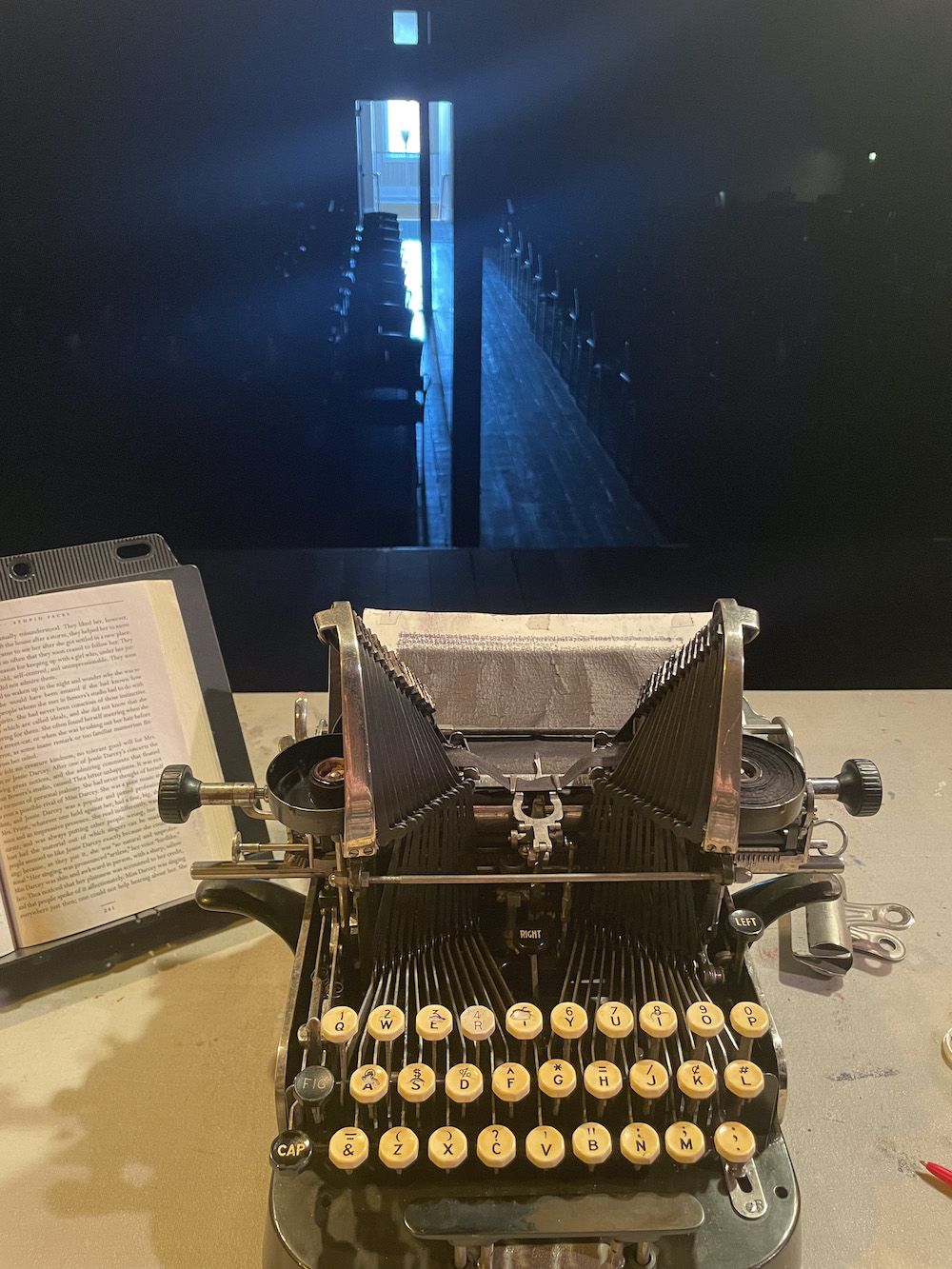

On the Road with Tim Youd’s 100 Novels ProjectWhen I first encountered Tim Youd, he was sitting at a metal table outside an art gallery in Chinatown, tap-tap-tapping away on a portable typewriter, just minding his own business. Most of the crowd didn’t pay him much mind either.

Earlier that summer, Youd found himself on the flatbed of a pickup truck parked in front of LA’s Terminal Annex Post Office retyping Charles Bukowski’s Post Office on an Underwood typewriter. That was in July of 2013 and proved to be a precursor to the LA performance artist’s ongoing “100 Novels Project” series, in which Youd visits the settings of one hundred novels and retypes them in their entirety on the same model typewriter that was used for the original composition. The Bukowski performance would become number 7, marking the beginning of these literary pilgrimages that would take Youd all over the world.

Now, almost a decade later, I’m in Red Cloud, Nebraska, to watch Youd (pronounced you’d) perform a retyping of Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. Speaking of larks: Could Youd have ever imagined his project taking him this far, literarily and geographically?

Tim Youd retyping Jack Kerouac’s Big Sur. Bixby Bridge, Big Sur, CA, July 2015, courtesy Cristin Tierney “I think that’s the great good fortune that I have happened upon,” Youd tells me over an espresso at the one coffee shop in Red Cloud, a small prairie town of around 1000 souls. We’re marveling at his journey thus far. Just name any well-known American author—been there, retyped that: Kurt Vonnegut, Upton Sinclair, Jack Kerouac, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Tom Wolfe. Cather’s The Song of the Lark is number 72—only 28 more to go. What can 10 years of intense drive and dedication possibly mean at this point, other than perhaps I’m talking to a well-read madman. “This thing has become way more expansively meaningful to me than I could have ever imagined in the first couple of retypings,” Youd exclaims, pondering the meaning of it all. “It’s become my whole life. It’s become everything.”

Willa Cather & Red Cloud

I took it upon myself to read some Willa Cather before I went to see Youd perform, starting with O Pioneers!, then moving on to The Song of the Lark. I was quickly hooked, and going to Cather’s Nebraska hometown made the read that much more meaningful. Red Cloud was Youd’s second stop of “The Prairie Trilogy,” aptly named for his literary pilgrimage to three Nebraska cities: Lincoln, Red Cloud and Omaha, inspired by Cather’s own Plains Trilogy: O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, My Antonia, all books highlighting the presence of the Great Plains, a landscape that had an undeniable influence on Cather throughout her formative years and young adult life.

The National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud (co-sponsors of The Prairie Trilogy project) hosted my stay in the tastefully restored historic building. When I arrived late in the evening, Candace Moeller, director of the Cristin Tierney gallery in New York (who represents Youd and are co-sponsors of the project), was at the center, waiting for me along with Youd. Mueller bought two bottles of wine and whipped up a pasta and salad. Youd had finished a day of typing. I’d just come from LA. It was a perfect way to end the evening with so much mirth at the kitchen table. Our conversation always circled back to reading and literature, which is almost unavoidable if Youd is in the room. We all turned in before midnight; tomorrow would be a busy day.

The next morning, I set out to visit the Willa Cather house, where Youd would be typing. It was sunny but brisk as I walked down the main street. Shuttered businesses mixed in with open shops: one bank, the post office, pharmacy, food market, bar—and a Subway (!)—all lining a red-brick road, probably the same bricks that Cather rode down in a horse and buggy.

Youd at Willa Cather’s childhood home. As I approached Cather’s childhood home, I could hear a distant tap-tap-tap, bing! Tap-tap-tap, bing! Birds were singing joyously—could they be larks? I sat down on the soft green grass in the front yard and watched Youd typing on the porch; the typewriter was ancient, an Oliver No. 3 with “wings” from 1898. Youd, 55, was dressed casually in a long-sleeved T-shirt and jeans. He has an impressive head of thick white hair, accented by his Clark Kent black-rimmed glasses. Youd was deeply absorbed. If he heard me coming, he didn’t show it. It was quiet, even with the tapping and chirping. The rhythm of the typing was hypnotic as I took in the surroundings and thought about Willa Cather and one of her main semi-autobiographical characters, Thea, who saw things differently but didn’t yet realize that she was an artist.

Later that day, I had the opportunity to enter the Cather house, which was included in a “town tour” the Cather center offers. Walking through each room felt like I was reading one of her novels in 3D. I climbed the narrow wooden steps to the attic, where Cather’s bedroom sprang to life: the tattered, faded, rose-patterned wallpaper, the floor-to-ceiling window, the bed where she brought hot bricks to place under the covers for warmth. Cather’s vivid description of her attic bedroom was eerie in its precision. My whole trip to Nebraska was beginning to seem surreal.

Typewriter Youd used for Cather novels: Oliver No. 3 with “wings” from 1898. No Fear or Loathing

One day back in 2012, Youd was sitting in his studio when he came up with the idea of retyping novels as an art project. He had just closed the book he was reading and started squeezing and pushing on it—he wanted to crush the book so he could “get all the words onto one page,” he tells me, pressing his hands together. The book became an object with a formal quality. There’s “a black rectangle inside of a white rectangle,” Youd says, referring to the text within the encompassing margin being the white rectangle. “I wanted the texture of the words, the weight of the words.” It had to be a typewriter because the book is typeset, he reasons. “It’s a font, and I want to echo that.”

Alone in his studio, he proceeded to retype Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, on an IBM Selectric—the same model Hunter S. Thompson used. Youd recalls feeling “happy, relatively speaking.” He was excited, thinking, “Wow, this is kind of a successful experiment, I want to do another.” So, he typed a few more novels in his studio, and it became clear to him then that the project should take the form of a literary pilgrimage. “It should be a public thing, where I go to a significant place in the author’s life or the setting of the book I’m retyping,” he recalls.

Mat Gleason of Coagula Curatorial gallery in Chinatown—where I first saw Youd typing—was showing Youd’s visual work and was a big proponent of this new project. He took Youd to art fairs in Miami and New York, and that’s when Youd’s career really took off, outside of LA. It was his retyping of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in Brooklyn that caught the attention of Cristin Tierney gallery.

Youd liked how things were going, but he knew that the pilgrimages would have to end at some point. That’s when he was struck with the idea of a list.

“Everyone has a list of something. I’m gonna type 100 best novels,” he remembers enthusiastically.

“I’m ambitious by nature,” he says matter-of-factly. “I like something big to tackle. And that felt pretty big!” Youd also liked the whole literary pilgrimage aspect of it all: “It’s whimsical. Almost a pop-culture thing that we do. We make journeys. We go to Graceland. We make pilgrimages. That’s the kind of people we are.” Who could argue? Besides, he notes, “It’s catchy. One hundred novels. I’m not just a guy going around the world typing novels. I’m typing 100 novels! People love numbers.”The Country Tour

The next day I was scheduled to go on the “country tour,” where Youd would be typing. It was another stunning day on the Great Plains as my tour guide drove us over the bumpy dirt roads in her SUV. We visited several tiny cemeteries and Willa Cather’s farmhouse—or rather what was left of it: a bit of foundation and a water pump. The countryside was lush with wildflowers, purple prairie clover, bunchgrasses, mulberry bushes and tall scraggly cottonwood trees, all described so tenderly in Cather’s novels. I was seeing the author’s words come to life and beginning to understand the gravity of Youd’s pilgrimages.

Youd typing at the Pavelka Farmstead, photo by Tulsa Kinney We arrived at our last stop, the Pavelka Farmstead, a historic house which was being renovated to host visiting scholars and interns. Youd was set up outside in front, typing intently. We interrupted him to see how it was going. He was nearing the end of the book—only 20 or so pages to go. The paper he was typing on was tattered and saturated with black ink, thin tears revealing the page underneath. Youd was excited to show us the diptych and pulled the two pages out of the typewriter. (It should be noted the novels are retyped over and over onto a top page, with a second page underneath. The top sheet naturally gets saturated with ink, often tearing through to the page underneath. They are displayed side-by-side as a diptych after each novel is finished.)

A Better Reader

When I asked Youd to describe his “reading” process, he readily answered my question: “Anything I’m typing, I’ve read before. So, there’s not going to be many surprises in the plots.” With his close reading of each word and sentence, “it’s a significantly heightened experience of reading versus when I read it the first time.” He’s also reading during the daytime, when he is most alert and receptive (not lying down!). “I’m devoting my whole day, the best I can give it.” This made me feel envious, and even a little guilty, as I usually reserve my reading for the end of the day, when I can barely finish a chapter before I start dozing off.

Is Youd’s project about optimizing his own personal reading experience? Isn’t that self-serving, selfish and self-indulgent (adjectives often associated with artists)? Does he have naysayers, people that are skeptical, or even jealous of him, like me? Youd admits that his art might not appeal to everyone. “People have come up to me and told me what I’m doing is stupid.” Once at a performance in a museum a woman was circling him. “I could hear her breathing and sighing,” Youd recalls, with a wry smile. “She was pissed off. She just hated what I was doing.” She left with a comment in the guest book: “The 100 Novels Project is singular in its uselessness.”

Elizabeth Bishop’s The Complete Poems, 1927 – 1979, 2018, courtesy Cristin Tierney. On The Prairie

It was my last day in Red Cloud, and Youd would be finishing retyping The Song of the Lark on the actual prairie. This time I followed my tour guide on “The Prairie Tour,” a five-mile drive outside the town. When we turned off the main highway it was as if we entered a Prairie Land movie in vivid Technicolor. (Were the homemade Swedish pastries I had that morning laced with LSD?) The prairie lay before us with tall wheat-yellow grass pressed against a blue sky dappled with white fluffy clouds. It was a majestic sight to behold. My guide informed us that these prairie lands are part of the Cather Foundation preservation program, of which they own over 600 acres. The goal is to return the land to its 19th-century conditions—before agriculture and foreign plant species despoiled the countryside. A noble deed that Willa Cather would highly approve of.

Finished diptych of The Song of the Lark retyped on the Prairie, photo by Tracy Tucker. Youd had been in Red Cloud for 18 days and retyped 430 pages of The Song of the Lark (her longest novel). He made several attempts to set up in the prairie land, but until now inclement weather conditions had stymied his plan. Today the weather was ideal, with a light warm breeze—a perfect day to conclude the project. Youd was already there when we arrived, with his table, book and typewriter set up in the tall grasses—and only 15 pages left to type. We didn’t linger to watch Youd perform. It seemed he should be alone for the occasion; he didn’t object to our leaving either.

After Youd finished his retyping of the novel, we ended our Red Cloud days at the local bar and grill, as I’d heard they make a great burger. I asked Youd if he was sad about ending his 72nd novel and leaving Red Cloud. “There is a melancholy aspect to literature in general,” he replied. “It’s about the passing of time. Time passes, and when enough time passes, [whether it be] the end of life, the end of a chapter of one’s life, or a relationship, there’s always a sense of sadness in the story.”

Youd didn’t have that much time to indulge the blues though. The next day he would be packing up and moving onto Omaha and retype Cather’s My Antonia at the Joslyn Art Museum (co-sponsors of the project), bringing The Prairie Trilogy to a closing. “I have a jumble of emotions on completing a novel. Especially completing a project in a location that is as close to perfect as it really can get,” he said, referring to the generous hospitality the Cather center provided. “To be out here, to be in the historic buildings, on the prairie that Cather knew as a child that she captures for us so vividly.”

Being on the prairie clinched it for me too. It really made Willa Cather’s stories come full circle. Was this the lesson I could take back with me? Art is supposed to open one’s eyes to new ways of seeing. Did Youd’s performances do the same for new ways of reading?

“I didn’t necessarily know, when I typed that first [novel], how it dawned on me that what I was trying to be was a good reader,” Youd muses. “Because that’s what the project is. It’s about trying to become a better reader each time you sit down, and measurably be in a different spot as a creative thinker, as a critical reader.”

Sadly, many people don’t read books at all anymore. What

often passes for reading these days is the content on social media. It’s been reported that younger folks spend around nine hours a day in front of a screen. Imagine what a difference it would make to that person’s life if they devoted even a few of those hours to reading a book.I know Tim Youd can imagine the difference; he’s made it his life’s work to do so. Let’s all take a lesson from Youd, and prioritize reading a book—in the middle of the day!

-

POEMS

“shift work” by Evan Evans; “Enduring Romance” by John Tottenhamshift work

twin heads pillow

moments away

only seats left in the front

the forgiving distortion

the forgetting of plot

so grateful

that the light should bow

to take the shape of your mouth

a movie where she’s

so tired

from watching him

sleep

all day

—Evan Evans

Enduring Romance

There was a time when you were charmed

by my lunging, and when I found your ignorance

more endearing. But that was long ago,

when love was new and our every precious moment

felt like sunlight glittering upon the edge

of a gently breaking wave. Now closeness

means chaos, and every dreaded moment

brings me closer to my grave.

Where does all this clumsy thrusting end?

Half-mad, greedily sucking on the

desecrated manhoodof the absentee father; desire meets boredom halfway

in a stalemate of discontent, a deep and selfish love

that can only thrive in a moist environment.

—John Tottenham

-

Poems

“Silicon Valley” by Rhiannon McGavin; “Vanity in Vain” by John TottenhamSilicon Valley

A cloud is the earth displaced for tracks of cable underground, underwater

A stream is the friction between content and a beckoning hand

To kindle is to adjust the climate dial in a server farm

An antenna is the arc of pesticide as it is sprayed from a plane

A bug is the noise emitted by neon signs

A web is the section of sky covered by a billboard

A nest is the time elapsed between waking and sensing an advertisement

An echo is the decomposition rate of post-consumer technological products

An amazon is the unprocessed pulp for one holiday’s supply of shipping boxes

An apple is the leaked transcript of a board meeting

A seed is one black redaction mark

To phish is when a red tree blooms in the warmest recorded January

A story is what disappears after 24 hours underground, underwater

Memory is less expensive each year

Memory is the sound a forest makes as it is felled

Memory is the thing that waits for room to grow

—Rhiannon McGavin

Vanity in Vain

To give up or give in,

to cease to take solace in

the things that I take solace in,

and give in to wanting

what everybody else wants.

That way lies ruin.

As vain, in vain, and unrewarding

as it’s been, the losing battle

I’ve chosen still beats the alternatives.

There’s no way out now, no return

to the collective dream.

—John Tottenham

-

Poems

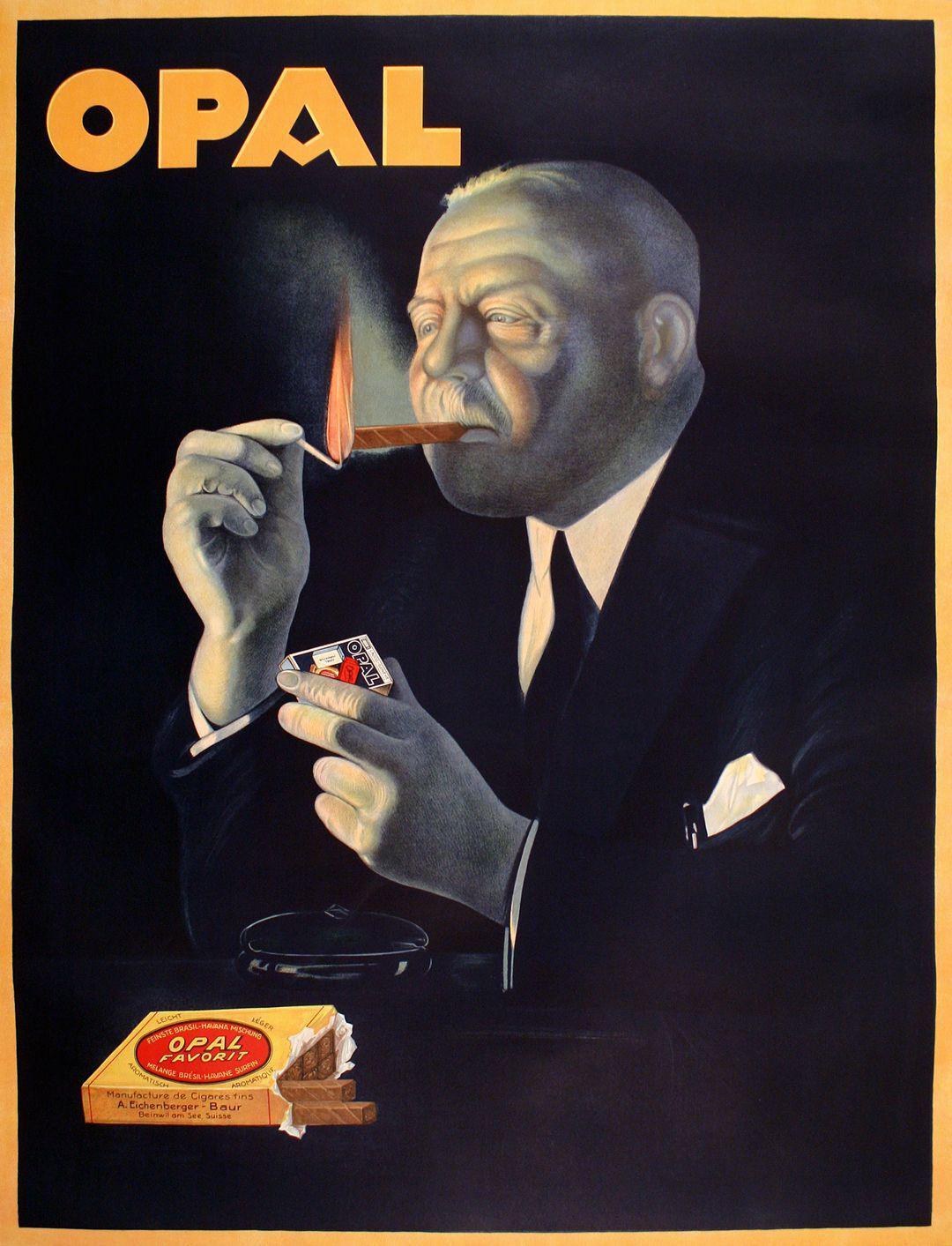

“Kiefer Lights a Big Cigar” by Klipschutz; “The Poet’s Garden” by John TottenhamKiefer Lights a Big Cigar

& waves the heavy machinery into place

He rearranges the rubble

speaking whichever language suits the occasion

He & Tony saunter through a tunnel in the South of France

“It’s my gesture” is what he says about his art

His use of lead & straw reminds me of a Jack Gilbert poem

Kiefer & Werner Herzog must never meet

If they have, they must never admit it

(When Gerhard Richter met Stockhausen

neither one was left unscathed)

Kiefer carries the weight of the world on his shoulders

& shakes it off with a flick of his cigar

—Klipschutz

The Poet’s Garden

Without these words, without these needs,

how much simpler life would be: free

from invidious and irrelevant comparisons,

resentful longings, and obscurely realized

self-actualizations: a life less whole,

a lifeless hole… but a destiny, at last,

within my control – striving

only towards resignation,

a worthy goal.

—John Tottenham

-

Poems

I Could Have Written That

By John Tottenham

Like you, I am tired

of my own voice,

these incessant I’s and me’s.

But what’s the alternative?

I don’t have the audacity

to employ another he or she

or We. Nothing could be worse,

psycholinguistically, than that sententious

and presumptuous first person plural,

which despite its unifying intentions,

seems to have an effect

that is entirely exclusionary.By William Minor

The Lovers

A man’s face may indicate

a tendency towards despair,

but it may also indicate a tendency

towards nothing in particular.

Sometimes a woman falls in love

with a man with this face.The Building

A mental hospital is just a building,

and a woman is just a person sitting in

a building.The Drawing

There are men who like to draw

and there are women who like to look

at wagons.The Journey

It is easy to imagine

a spiritual journey

lacking in grandeur.