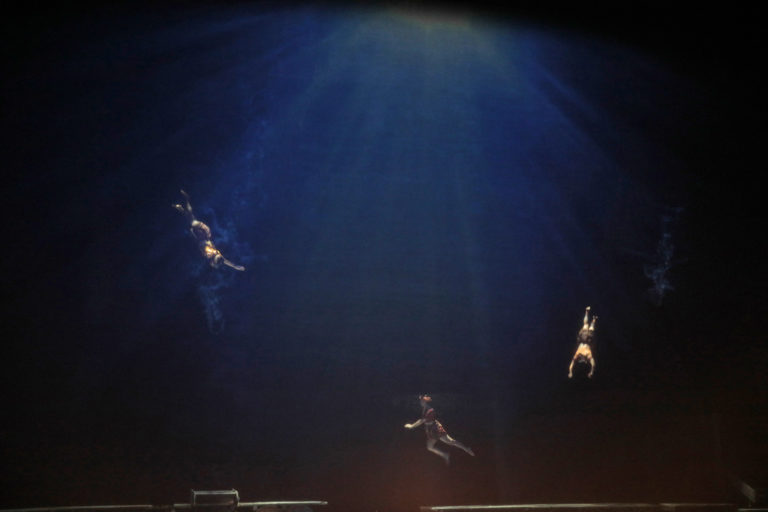

“Jesus, you know, it wasn’t supposed to happen like this. Even if it strikes me now as having been inevitable….” “I want to know what it will be like once all this (all this: the inexorable, the inexpressible) has become distant memory. I’ve always hated the way...