Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Jeffrey Vallance

-

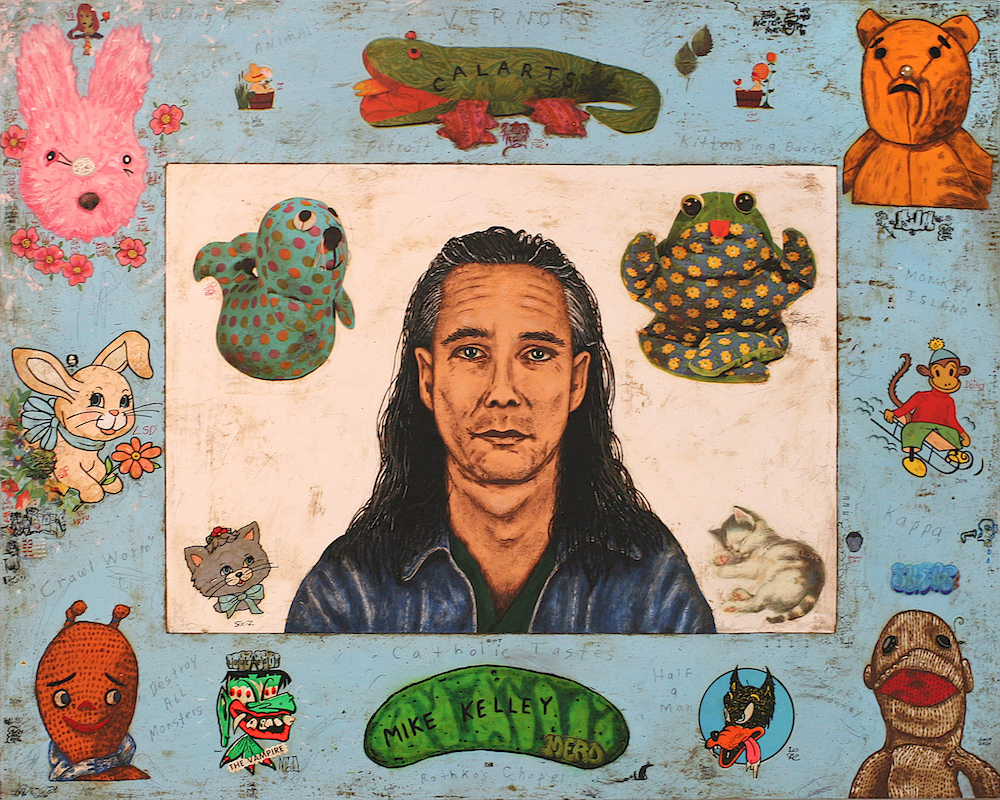

A Few of Jeffrey Vallance’s Favorite Things

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”] [et_pb_row admin_label=”row”] [et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]Jeffrey Vallance holds a unique position in the LA art world. A contemporary of Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Jim Shaw, et al, his work has had a comparable impact locally and internationally, while not transitioning to the industrial fabrication mode demanded by the global fiscal laundromat subdivision AKA The Art World. Part of the reason is that he’s actually from LA—the Valley, specifically—which somehow means you can’t actually represent LA to the rest of TAW.

Mostly though, it’s because Vallance responded to his initial burst of fame by embarking on an extended peripatetic global R&D expedition that had nothing to do with Kunsthallen, art fairs, or high-end public art commissions, but rather Kings of Tonga, Presidents of Iceland, and Las Vegas vanity museums. He never so much fell off The Art World’s radar as evaded capture like some international man of mystery.

Yet another factor is that Vallance writes about his own projects better than any hack critic could, with a deadpan humor and open-mindedness completely analogous to his idiosyncratic semiotic investigations. In 1995, in conjunction with a survey show at SMMOA, Art Issues Press published The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978–1994—encompassing the Tonga and Iceland adventures, as well as his first forays into paranormal reportage and, of course, the last (and subsequent) rites of Blinky the Friendly Hen—the Ralph’s fryer whose pet cemetery funeral service landed Vallance on Letterman and MTV.

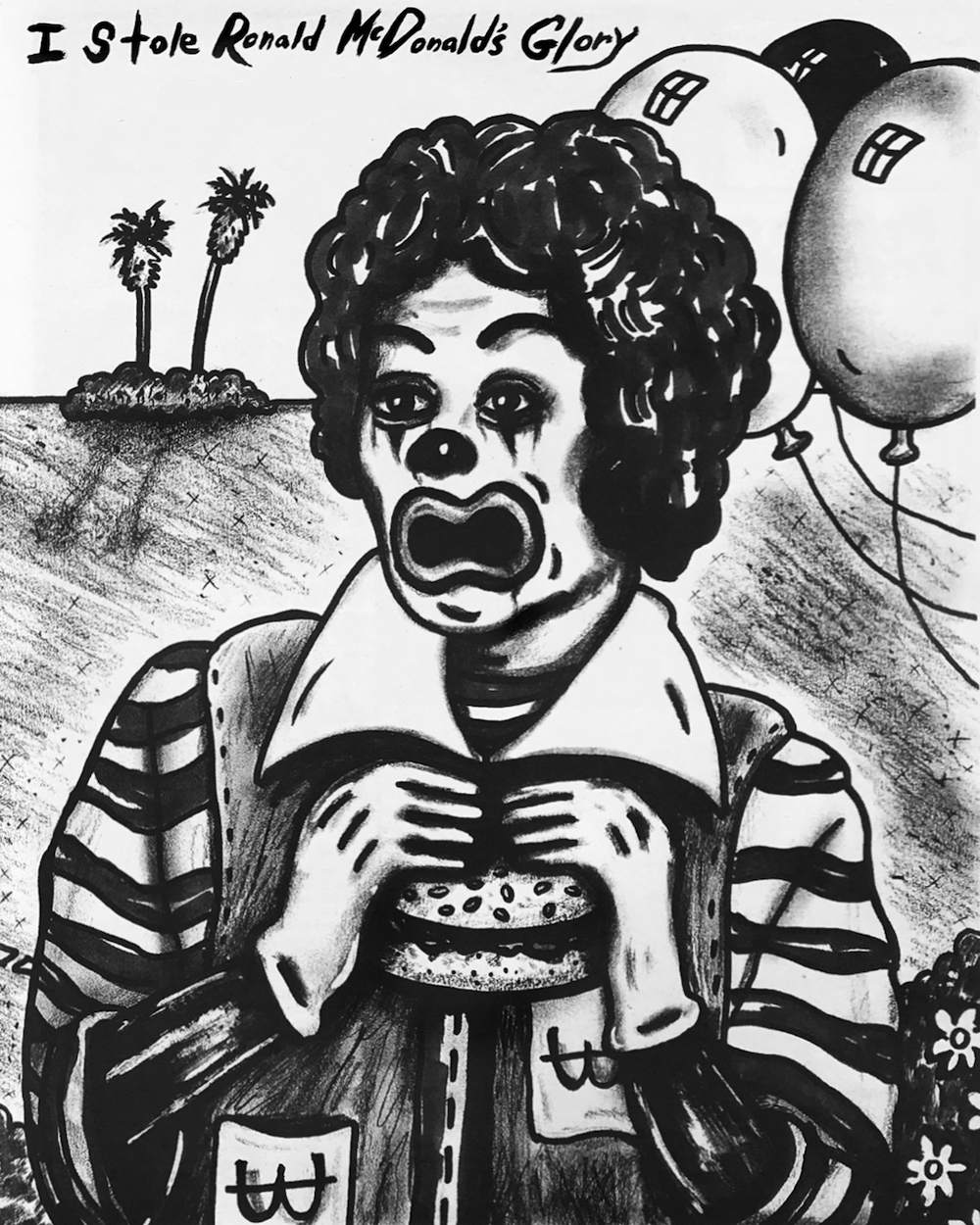

Jeffrey Vallance, The Clowns of Turin: Found on the Holy Shroud, 1996. Collage, pencil and marker on paper, 22 x 29 ¾ in. Collection of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA. Long overdue, A Voyage to Extremes: Selected Spiritual Writings collects close to 700 pages of Vallance’s musings and reports from the intervening decades. That may sound daunting, but this ain’t War & Peace—nor Being and Nothingness neither. Not that it isn’t narratively compelling or philosophically deep—but it’s funny.

And entertaining in many other ways—strangely informative like the best internet curations, or like your weird uncle who gave you Charles Fort’s The Book of the Damned and a sealed vinyl copy of Spiro T. Agnew Speaks Out for your 12th Kwanzaa. A hundred little stories forming a cubist mosaic of a singular artist’s singular journey.

Art historically, the ginormous yellow tome is a gold mine, providing off-the-cuff anecdotal accounts of Vallance’s legendary curatorial interventions in various offbeat thematic museums in Vegas, while elsewhere detailing extensive cross-cultural

research into the religious, anthropological and philosophical significance of clowns.As promised by the subtitle, much of the work addresses spirituality, religion, shamanism and paranormal phenomenology. Richard Nixon, Thomas Kinkade, Martin Luther, Charlie Manson, Ronald McDonald, the Loch Ness Monster and other spiritual teachers all make appearances. It’s not a fluke that Vallance’s curiosity-driven ideational flow is so reminiscent of an extended Wikipedia surf.

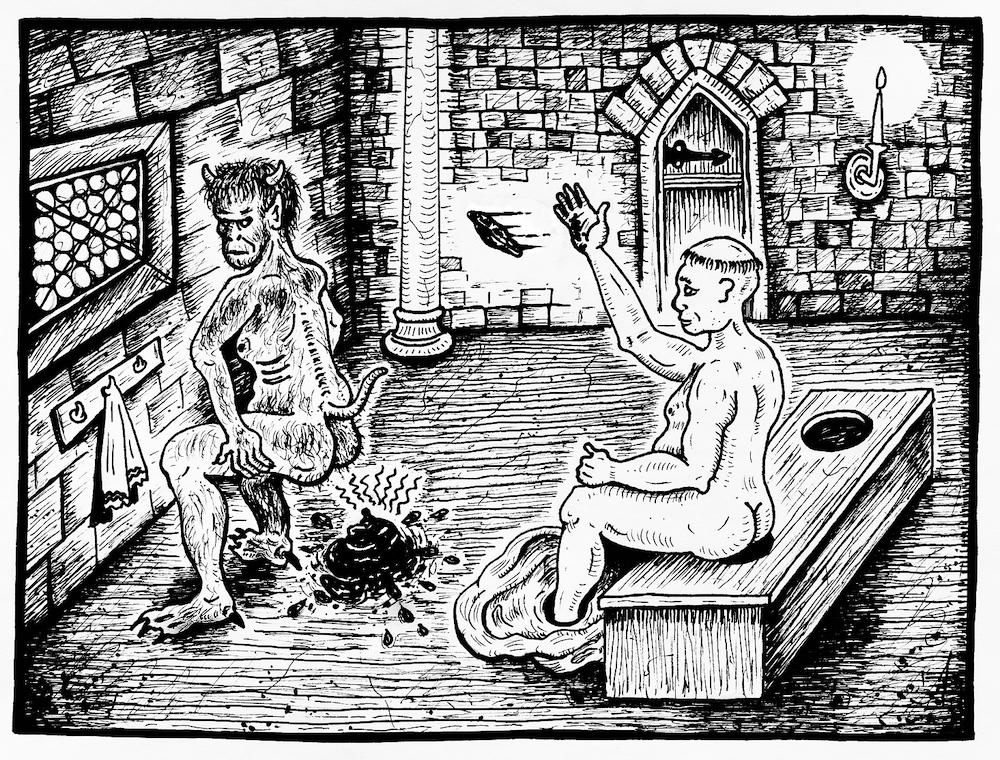

Jeffrey Vallance, Luther on the Privy, Seeing an Apparition of the Devil, 2000. Courtesy of Jeffrey Vallance and Tanya Bonakdar. Much of Vallance’s most significant recent works have been embodied—however ephemerally—in his absurd and prolific social media activity, with Facebook groups that range from the absolutely authentic Valley Plein Air Club to the mind-scrambling Polytheistic Butt Plugs.

Consequently, Vallance’s Voyage to Extremes seems to me to be the most successful literary embodiment of the human cognitive structures that have evolved with the internet—not from imitation, but from pre-existing structural resonance. A playful, weightless curiosity may seem like a fey and inconsequential thing, but when it drifts across a border as if the border wasn’t there, watch out! That’s when Luther’s excrement hits the Devil’s fan! And that’s why the internet is still (though sadly less and less) dangerous.

In counterpoint to this ADHD-currency, Vallance has provided a newly written overarching autobiographical framework. Arranged approximately chronologically, the included materials chart Vallance’s aforementioned trips, his mythic residencies in Vegas and Umea (Sweden), and his return to the San Fernando Valley (from whence he deploys his current, peculiar global/local influence).

This interstitial narrative skeleton generates a knowing—occasionally dark, even justifiably bitter—storyline detailing the obstacles and joys of being an artist in the 21st century, from which the oddball essays radiate like feathers on a bipolar peacock. The power of art to short circuit the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune have never been articulated more elegantly.

From excrement to ecstasy, from Texas to the Arctic Circle, from the taxonomy of butt plugs to the etymology of the Tetragrammaton—all the indeterminate territories TAW tiptoes around—Jeffrey Vallance relentlessly but non-aggressively burrows beneath, collapsing rickety categorical imperatives in favor of rhizomatic ‘patacritical revelations that are equal parts Art Bell, Roland Barthes, and S.J. Perelman. Copiously illustrated.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section] -

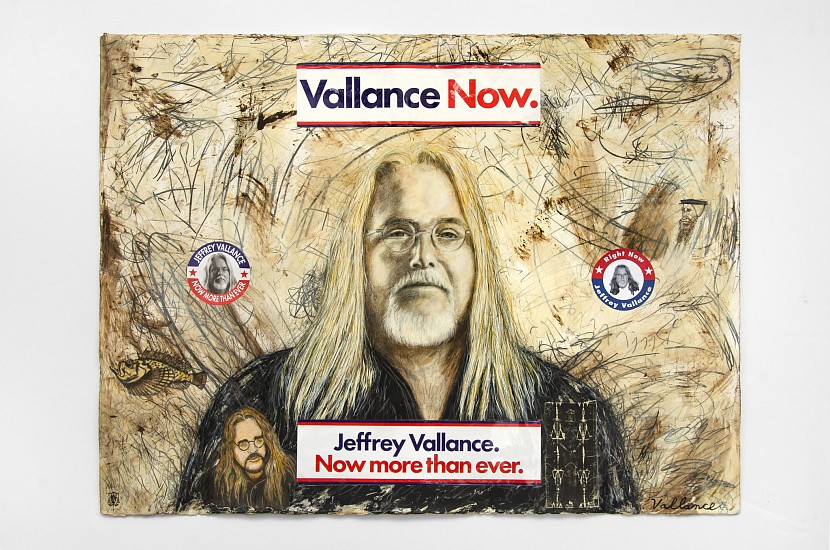

Jeffrey Vallance: Now More Than Ever

Jeffrey Vallance was already something of a legend when I first became acquainted with his work – an ‘interventionist’ style of conceptual art in which the performance became a kind of deconstructed cultural inquiry. My first impression came by way of captioned illustrations with accompanying narrative (appearing in the L.A. Weekly), a kind of anthropological scrapbook replete with schematic drawings of quasi-iconic images, national insignia, commercial artifacts, transit documents and correspondence with government bureaucrats. Not long thereafter, Vallance revisited the subject of a prior and more local cultural inquiry, touching on the side-by-side domestication of pets and predators – specifically, what may be the world’s most famous domesticated – and slaughtered – hen, Blinky, whose exhumation was documented in a show at the Rosamund Felsen Gallery. Having crossed many lines over the successive decades, Vallance has returned to the quasi-iconic by way of the most essential, cryptic and automatic mark-making; in effect (as Doug Harvey might have it) ‘erasing’ virtual lines between the historically enshrined and presently reimagined, archaeological residue and speculative projection, truth and legend. Vallance’s current show at Edward Cella is both an exhibition of these new works, born out of a mark-making Vallance characterizes (in homage to Blinky?) as “chicken scratches,” and a quasi-retrospective celebration of his entire body of work (a massive stack of flat files containing an enormous archive of his drawings is the centerpiece of the main gallery). His engagement with the myths and actualities of many of the world’s leading political figures is also celebrated – ‘with tentacles extended.’ ‘Do we really need to see this show?’ you might ask. Now more than ever.

Edward Cella Art & Architecture

2754 S. La Cienega Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90034

Show runs thru December 31, 2016 -

Smoke and Mirrors – Per omnia saecula saeculorum

Jeffrey Vallance’s séance/performance, Ghost Writers – a collaboration with the self-titled psychic astrologer, Joseph Ross, held in conjunction with Vallance’s show at CB1 Gallery, The Medium Is the Message – was ostensibly intended to draw out the spirits (and opinions) of art critics past (Vallance has not lacked for critical commentary in the local or contemporary art press), to sound off against Vallance’s photo-montaged artist-icons displayed on the surrounding gallery walls – themselves previously channeled by psychics in Vallance-led performances (e.g., at the last Frieze Fair). But the actual effect was more of an invocation directed at his entire audience of culture consumers.

The spirit of the invocation derived more from the 19th century than the 20th or 21st. Mr. Ross has appeared in varying costume for his séances, but on this particular evening, he seemed to be playing a mid-20th century version of the dandy, albeit one conceived in 19th century spirit, attired head to toe in lavender – lavender suit, lavender-banded fedora, and white and lavender spectator shoes. An electric candelabra flickered at his feet as Vallance tried to massage a few channeled spirits from his medium. They came almost too easily and perhaps predictably – two dandies of 19th century criticism (and art). “Hello, I’m Oscar Wilde…. Does anybody know who I am?” Naturally, he immediately made reference to Wilde’s famous essay, “The Critic As Artist,” written in the form of a quasi-Platonic dialogue (that would have made Plato howl – probably with fury, but not without laughter). I didn’t recognize any direct quotes from the essay, and he may have even contradicted a few of Wilde’s actual points, but he caught the spirit of the thing, which attempts to dissolve the distinctions between art-making and its criticism. Wilde was making a larger point in “The Critic,” but the subsidiary point of artistic choice and selection as functions of critical thinking applied. He segued from Wilde to Baudelaire, whose spirit has abided close to the art world since he first took it on in the mid-19th century – the ambiguous divide between the sacred and profane, innocence and corruption, the perfume of decay, the respiration of civilization’s rise and fall – yeah, we get it….

I had the sense that Vallance was trying to draw out a few more spirits, critical or otherwise, from Ross; but he gave his ‘medium’ a pretty free rein. As promised, Vallance eventually urged Ross toward the photographic portraits hanging on the gallery walls, beginning – an appropriate segue from Wilde – with Salvador Dali. “This is not a bad likeness….” Indeed it wasn’t. I wasn’t sure of the photographic sources (the Dali portrait looked vaguely like one of Halsman’s), but with the possible exception of the Warhol, Vallance’s choices were fantastic. (And of course Warhol’s best portraits were his own.) “The face looks like me.” Then, comparing himself to his peers in the gallery – “None of them changed the world. I did. I’ve recreated the planet…. Now I’m redesigning the universe.” (That would be a stretch, even for Wilde.) Then Ross spoke in his own voice, coming back to himself, and the tune changed. “It’s [Dali’s work] great art, but outmoded and behind the times. He was not a good surrealist. He was a royalist.” (Were the two qualities incompatible?) “I am Joseph, so there is an overlap,” he explained to the audience who might have missed the transition.

“I’m a little afraid,…” Jeffrey began, leading Ross to his next subject, Vincent van Gogh. This was a good likeness, too – under the haze of what looked like a lap dissolve – of Kirk Douglas, playing van Gogh in the 1956 M-G-M film, Lust for Life. Vallance tried to coax the spirit out with the pinprick of the present. “No one would buy your work [when you were alive]…. How do you feel now that the same [sort of] people are buying all your work …?”

“Well at least they didn’t crucify me,” was van Gogh’s Ross-mediated reply.

Somewhere between Warhol and Duchamp, Vallance tried to pull another critic out of Ross – less famous, but one of the first to recognize and write about him. This was the Los Angeles Times’ William Wilson. Ross couldn’t really put a bead on Wilson, but was game enough to offer, “My mind is here, but not my body.” And more tenderly, “I love you Jeffrey.”

“Not that I’m trying to get press at my own show….” Vallance retreated a bit.

In Warhol’s voice (seemingly), Ross was confessional. “I love everybody and everything…. I always thought I was a charlatan. Yet you all loved me.” Then he somehow free-rationalized his way to, “ … because all you artists are parasites….” Likeness aside (Andy looks like a French philosophy professor), the Warhol portrait is a hoot, with Valerie Solanis buried so deeply amid the dark photographic layers that I thought for a moment she was actually the Velvet Underground’s Mo Tucker. In the smoke swirling around his wig, a smaller photo-composite is set into a cloud with one of Warhol’s Eve Arden-esque ‘Marilyn’ drag photos teasing us with the Avedon reveal of his post-assassination scarring. Smoke swirls everywhere in these portraits, including (naturally) the portraits of Marcel Duchamp and Jackson Pollack – perhaps drawing out Ross’s own moodiness. “I was a handsome man,” he said, in ‘Duchamp’s’ voice. “I was an intellectual, more than an artist.” ‘Truth’ to one side, that didn’t sound right at all; and by this time, the ‘voicing’ became a bit loose, even unhinged; and possibly verging on anger (which I think must have delighted Vallance). “Anyone in the art world besides the artist is an imposter.” (Can’t argue with that….) “The critics are the insane ones.” Hmmm…. At one point, there was a real break where Ross suddenly began to speak in the excoriating ‘critical’ voice of the late Senator Jesse Helms.

In a second gallery, Vallance showed objects associated with the artists – products of his own personal association with the artists – if not their actual artistic ‘spirits,’ then the spirits and associations channeled through their self-annointed surrogates (e.g., at Frieze – a video of which was also exhibited here). Some of these were simply fantastic. Vallance has always had a fascination for the paraphernalia of religious liturgy, the sacral and sacerdotal; also for the cultural critique viewed through an archaeological lens: the way we die; the way we lived; and what we leave behind; how cultural symbols and symptoms are reduced to a systematized symbolism and symptomatology. (And I’m getting way too sibilant here….) The best one here was the least sacerdotal: a beer jug stamped “One Trick Pony,” with a small engraving rolled up and extending out of the neck – riffing off the line attributed to Leonardo that was paraphrased along the lines, “I’m the only real artist here; the rest of you [my artistic peers] are just one-trick ponies.” It looked primed for its next ‘incarnation’ as a Molotov cocktail.

Art becomes self-consciously critical and somewhat reflexive as early as the late Renaissance; but there’s no denying that the self-critical aspect becomes increasingly pronounced since Romanticism (and Baudelaire) – with the sharpest break coming after World War I in Dada and Surrealism. We’re seeing another break now in the transition between Conceptualism and post-Conceptual art, where culture seems to be not merely criticizing, but consuming itself. Glancing at the rapt, respectful audience at Saturday’s tour via séance, I felt enclosed in a sarcophagus, insulated yet awaiting immolation as the culture of smoke and mirrors crashed around us – and not sure if this was the way I wanted to go. Better to throw that first Molotov cocktail.