Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Gabriel Fauré

-

Sun & Sea — Geffen Contemporary, MOCA, October 15, 2021

On the Beach — Now and ForeverNothing really happens in Sun & Sea, an opera set during a time in which we may expect ‘things’ will more or less stop happening altogether; or in any case, when things only happen to us—excepting possibly those wealthy enough to have provided themselves luxury-fitted underground berm or mountainside bunkers and the like. (Or, given flooding risks, they may prefer to fall back on Switzerland—still the last resort in every sense.) Come to think of it, we may be looking at a few such survivors among the human (and one canine) tide pool specimens strewn about this sandbox stage.

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance.

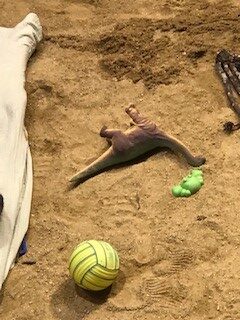

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance. It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

The songs and arias are very simply structured—rising and falling waves of just a few notes, or repeated patterns against staccato rhythmic lines, usually ending where they start or just slightly more resolved in one long sustained note or chord. After a few ‘undersung’ preliminaries establishing the emerging pre-catastrophic context, the beach-goers from their various places on the beach collectively intone a choral read of the beach conditions. From here we move on to the more individualized narratives: of losses that can scarcely be felt or acknowledged (a ‘siren’ singing of her deceased husband—drowned off just such a beach); a preening (more than doting) mother rhapsodizing (in pared-down fashion) about her accomplished (or at least well-traveled) child; a workaholic’s (her husband?) ode to exhaustion (which has a kind of stamped-out wheeze that fits both the tune and the character)—while the ensemble as a whole reminds themselves to keep their children close.

The Lithuanian ensemble that has put this musical and theatrical vessel together (consisting of Lapelytė, the librettist, Vaiva Grainytė, and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė) has very consciously set off this beachscape of human flotsam against the almost clinical view of its audience. If we enter and assemble around the gallery as if in a church choir, our view, gazing down into this vessel of near white light mitigated only by the swimsuits and flesh tones of the performers, is not unlike that of a surgical operating theatre. (Hard not to be conscious of just how close we are to something which in the not-too-distant future may resemble a coroner’s autopsy. The lighting was high-noon beach-bright; fortunately, my photo-sensitive eyes made it through without sunglasses.) As the audience begins to take the measure of this landscape—both physical and psychological—the tone (both musical and emotional) begins to shift slightly to the interior landscapes at some distance from the staged actuality—towards dream, towards irony. Yet within this operating theatre, even this ‘dream’ musing has an aspect of hard realism.

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

But the songs (and singing) added their own color—more frequently in the higher, soprano registers. (Philip Glass’s influence seems increasingly pervasive as the opera unfolds, and especially in the middle sections of the opera.) And color is what is increasingly evoked—not the phosphorescence of a healthy sea, but the unnatural or unseasonal colors and atmospheric conditions of an aquatic habitat under dire threat. Catastrophic human incident merely underscores human puniness in the face of planetary collapse. The music finally takes on the aspect of almost existential despair leading up to what finally becomes a soaring lamentation of anticipated absorption into an aquatic necropolis that renders our own human memorials pathetic and absurd.

And so (as Sonny and Cher once sang) the beat goes on. Will we continue to sing after the apocalypse? I feel neither happiness nor sadness in saying we almost certainly will. Less certain is whether we will work in quite the same ways leading up to it and in its aftermath (though biochemists, archaeologists and toxicologists are sure to have their work cut out for them). Will we fly or even move around the way we have over the last century or so? Hard to say; but—with Nico on my mind, as she has been off and on over the last few weeks (more on that for another post)—I would say we will continue to wander. (I heard her harmonium wheeze as much as, say, Fauré, through the show’s more ecclesiastical passages.)

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that other iconic “Beach” drama of the apocalypse may have put its finger on the point more precisely: “There is still time….” until there is no time at all.

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that other iconic “Beach” drama of the apocalypse may have put its finger on the point more precisely: “There is still time….” until there is no time at all.

-

Renée Fleming’s Long Goodbye

Entre le coucher de soleil et le clair de lune, les feux d’artifice nous appellent encore.

There is something tragic about the decline of a great operatic voice. It’s a tragedy that encompasses all the smaller tragedies of decline – including our own individually declining, decaying, debilitated and ultimately disappearing voices – precisely because of what that singular voice has encompassed entirely by itself. Also compelling – we cannot turn away or turn our ear from it – there’s something sublime about it comparable to other variously exquisite or spectacular natural erosions, even catastrophes.

There were no catastrophes Tuesday evening during Renée Fleming’s recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion; and probably more sublime moments than we had any right to expect. As landings go, it inclined to the side of soft rather than spectacular. It is not strictly speaking the end of Fleming’s operatic career – more accurately a segue from the operatic stage to a broader vocal and theatrical platform, which will include Broadway and other concert and theatre appearances. She made a point of reminding her audience that she would be opening in the upcoming Broadway revival of Carousel (in the role of Nettie) in little more than a month (previews will actually begin at the end of the month); and there were more than a couple of Broadway moments in the evening’s program.

Still given her final ‘hand-off’ of the Rosenkavalier, so to speak, this was something of a historic moment. She was already a star (with the Marschallin and both Donnas Anna and Elvira, among many other signature roles behind her) when she performed her first L.A. recital here in 1999 and has pressed on with fresh roles well into this decade. It has really only been within the past few years that there was even the slightest hint she might be loosening her hold on a unique and almost unparalleled vocal franchise. (I mean – this is an operatic superstar who has worked with Brad Mehldau and Charlie Haden, as well as Jean-Yves Thibeaudet and countless other classical soloists and ensembles.) Even in 2009, she could bring the house down at the Met with her Marschallin. (And I almost wonder if the Met itself factors into this. For all its glories, it’s a big house; and there are other historic transitions to consider – James Levine’s departure among them.)

I wasn’t necessarily expecting Strauss’ Four Last Songs (which incidentally she’s recorded twice); but, well … ironic that the only Straus we heard from was Oscar – on the heels of Fauré and “Les feux d’artifice t’appellent” from Rufus Wainwright’s opera, Prima Donna. In a way the suite of Brahms lieder she made up from several different series and cycles composed over the course of his career took the place of that more darkly chromatic terrain. The only familiar song here (for me anyway) was probably the famous Brahms Lullaby – or “Wiegenlied.” These seemed the most adventurous sequence if not an artistic high point for the evening; but (not untypically) Fleming was really still warming up. By the second half of the program, covering material she owns (e.g., the Fauré, the “Song to the Moon” from Rusalka) we were given a rich draught of Fleming’s voice in its full-bloom glory. Still, I couldn’t help missing a taste of her bel canto, say something from Rossini’s Armida (another signature role), or (keeping to the dark side), Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia.

Fleming is no less cognizant of the ‘darkness’ of this moment than anyone else; and I thought even her dress expressed it – a kind of gray-veined marbled silk (or perhaps mimicking Hockney’s swimming pool reflections – except in wintry gray; the dress, I learned from the Los Angeles Times, was by Carolina Herrera) and paired with a cape that looked like Hokusai-etched waves or ribbons carved out of graphite silk. (She wore a sapphire strass-strewn dress in the second half.) “Ombra mai fu” (from Serse) is not exactly a surprise on just about any recital program; but for that very reason surprised me here. The “Bel piacer e godere” from Agrippina – with its sophisticated and technically demanding syntax of tightly woven legato and staccato phrasing, almost foreshadowing the bel canto to come in the next century, seemed more appropriate to Fleming’s virtuoso instrument. But transitions between registers (a Fleming strength) seemed less than secure; ornaments were intermittently almost swallowed; high notes approached before definite landing. She was finding a certain ‘level’ here – but the effect was pallid and not up to her usually Handel-worthy standard.

But again – this was the not-unexpected Fleming warm-up. In the Brahms lieder, she (and we) connected with the lushness of her voice and the full scope of its expressive power. When she sang of the sternklar and silvery moons, the silver of the imagery was matched by her tone in a very secure upper register, and as “als flöge sie nach Haus,” we were flying right beside her. As Fleming made her way through the suite, it was as if she accessed every part of her voice and technique, amplifying a sense of musical/lyrical discovery for those of us unfamiliar with some of these lieder. The “Vergebliches Ständchen” made a witty but tender pendant to the “Lullaby” that preceded it. Obviously no one was in danger of freezing here, and Fleming had us all pretty much melted down by this point. She continued in very fresh terrain with two songs by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Caroline Shaw – the lines of the settings seemed to attempt to match the arc of the musical line, though with inconsistent effect. “Bed of Letters” actually began on a hum (which made me think absurdly of Streisand and Alan and Marilyn Bergman – where do you go with this?). It had the makings of a beautiful song, but despite its neatly wrapped-up verse, seemed somehow less than fully resolved.

I would have loved to hear her plunge more deeply into the repertoire of French art songs – from Fauré to Debussy, and possibly into, say Henri Dutilleux or Reynaldo Hahn. (The Debussy “Tombeau des naiades” – which she’s recorded – would have made a dazzling finish.) But set to Verlaine’s poem with its ‘masques et bergamasques charmants’ and ‘grands jets d’eau’, there was more than a little Debussy and Ravel already built into “Clair de lune.” Pairing it with “Mandoline,” she spun their ‘lunar’ magic into an ‘ecstatic’ moment. And she was clearly making it her own – moving into the Rufus Wainwright and Oscar Straus which in turn had an air of foreshadowing.

With Broadway in her sightlines, she moved to what was styled as a pre-finale interlude – a tribute to the great Broadway, club and cabaret singer (and apparently her neighbor), Barbara Cook – with audience participation on the Rodgers & Hammerstein “Whistle A Happy Tune.” One consistent through-line in Fleming’s career has been her willingness to venture far from her comfort zone. Strauss, Berg and Handel are pretty demanding as comfort zones go; but whether a matter of the moment or an excess of reverence, the delivery seemed slightly strained – hard to imagine, given that the preceding song, “Til There Was You,” (debuted by Cook and a signature) has been recorded by just about everyone (e.g., The Beatles), but there you are. For myself, I felt comforted when she moved on to the Dvořák that is stamped with her own signature – including the “Song to the Moon” from Rusalka that brought the recital to a sublime finish. It hardly mattered that the aria is largely placed in a kind of ‘comfort zone’ for her voice (albeit an expansive one). Here, as in the earlier Fauré songs and some of the Brahms lieder, the breadth and richness of her lyric soprano were fully exposed and articulated.

It is worth taking a moment to consider the richness and resourcefulness of that instrument; it couldn’t have been far from the mind of everyone in the audience. It was at the back of my mind almost from the first break between the Handel and Brahms: the qualities that set apart the divas who endure from those who don’t. It wasn’t difficult to set aside one’s quibbling demand for a silvery staccato when we could reasonably expect Fleming to deliver the beaten gold of her middle register (and really her entire range) well into the rest of the program. There have been a number of those in the latter camp who have made a success with Handel and the Baroque or alternatively, veering towards the coloratura range, with Wagner, Verdi, or Donizetti and the bel canto repertoire, yet who can’t quite bring off the big romantic roles – Manon, Thaïs, Mimi (or Musetta) – or the Marschallin. (Fleming herself has occasionally expressed frustration and regret and not being able to ‘do it all.’) Or simply sustain it all over the long haul – it’s a bit of a trick, requiring both serious planning and sheer luck.

Then there are all the imponderable factors that take it to that platform of celebrity seemingly reserved alternately for the most tragic figures (e.g., Callas), or those who endure to achieve quasi-landmark status in the larger cultural mainstream. Fleming, who like Beverly Sills before her, is sometimes called a ‘people’s’ diva, seems destined to follow in Sills’ footsteps. (She is already playing this kind of role with the Lyric Opera of Chicago.) But the ‘imponderables’ I’m thinking about here are purely vocal and musical rather than simply career-professional. Fleming’s voice as a vocal and operatic instrument has few equals in this century or the last. Elizabeth Schwarzkopf probably comes closest and provides a useful technical standard of comparison. (Also Victoria de los Angeles and Lucia Popp, based upon the same criteria. Elly Ameling, Renata Tebaldi, and Leontyne Price occupy a similar vocal terroir – though I don’t think even they quite match Fleming’s expressive range.) The Strauss of the Marschallin – a signature role – might also serve as a kind of molecular breakdown of the vocal signature. This is a voice characterized by generosity – pouring itself tonally and timbrally into every note of a phrase (another reason why its relative scarcity on the odd occasion seems all the more glaring). The articulation is also thoroughly and brilliantly thought-out, with a clear view (and ear) to how it’s going to land on the note and in the audience. I guess we could also call this acting – but Fleming’s ear and voice for the musical/lyrical nuance takes it to another level. There are so many ambiguities expressed in the role of the Marschallin, Empson could write another book on them; and Fleming pretty much wraps them all up and sets them ablaze. And – touching on that larger cultural dimension – Fleming understands something of the way the music delivers an entire world and way of looking at it (and listening to it) in a single phrase, and connects the audience to it almost viscerally. Our memory of a great Fleming performance is practically muscular as much as musical. It has a power that is almost panoramic. Songs about the moon are a cliché worn to obliteration; but when the voice seems capable of serving that cratered orb in your lap, we give it due consideration.

Capping off the evening with a few encores, Fleming returned to that silvery domain in Puccini’s “O mio babbino caro” (from Gianni Schicchi), before returning to Broadway with Lerner & Loewe and a nod to the Bernstein centenary – and on a deft political note, the ‘Dreamers’ (and maybe all of us dreaming of a “time and place” after the Terror we seem to be living through currently) – in “Somewhere” (from West Side Story). “I Could Have Danced All Night” is a bit worn as encores go, and certainly Fleming was conscious of a certain ironic density; but on this particular Tuesday evening, most of the audience would have willingly danced right beside her – all night, and to the end of love.

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance.

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance. It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that