Nothing really happens in Sun & Sea, an opera set during a time in which we may expect ‘things’ will more or less stop happening altogether; or in any case, when things only happen to us—excepting possibly those wealthy enough to have provided themselves luxury-fitted underground berm or mountainside bunkers and the like. (Or, given flooding risks, they may prefer to fall back on Switzerland—still the last resort in every sense.) Come to think of it, we may be looking at a few such survivors among the human (and one canine) tide pool specimens strewn about this sandbox stage.

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance.

Originally produced for the Lithuanian National Gallery, the opera’s libretto was translated into English and the production presented as Lithuania’s principal contribution (as curated by Lucia Pietroiusti) to the 2019 Venice Biennale (where it won the Golden Lion). Staged at the Geffen Contemporary with impressive fidelity to the original production, audience expectations were in suspense if not simply minimized, as everyone filed into the upstairs gallery—which felt something like climbing into the choir of a church where (again, no big surprise) we listened to the chanting of a chorale that ended more or less as it began. There are arias contained within this particular chorale structure (the opera composed by Lina Lapelytė)—but they come at us as wishful (or wistful?) exhalations (Sun & Sea assumes the oceans and seas will be sufficiently viable to accommodate unassisted breathing)—the casual observations, speculations, suggestions, declarations, and complaints we might once have shared with our families, beach buddies or fellow beach-goers within beach-blanket shouting distance.

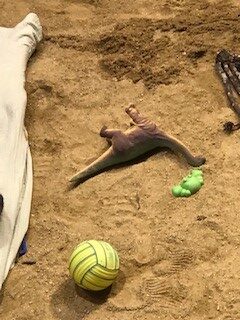

It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

It’s just an ordinary day at the beach—where people swim, surf or body-surf, sail, sun-bathe, or just laze in the sand; play small, self-contained games or toss balls to each other; picnic, play cards or board games; walk dogs or pets; read—leisurely, lazily, purposefully (workaholics will be with us to the bitter end), converse, or just watch the water—in delight or contentment, or impatient and complaining. The overall tone and atmosphere is not really conversational: these are elegies over the water—delivered to no one and everyone, evincing nostalgia, regret, or despair mingled with vestiges of hope, also community. People are variously optimistic or pessimistic—or have no expectations whatsoever. (In other words, we’ll be going down with the sea more or less the way we emerged from it, the only difference being that some of us may still be looking at our mobile devices.)

The songs and arias are very simply structured—rising and falling waves of just a few notes, or repeated patterns against staccato rhythmic lines, usually ending where they start or just slightly more resolved in one long sustained note or chord. After a few ‘undersung’ preliminaries establishing the emerging pre-catastrophic context, the beach-goers from their various places on the beach collectively intone a choral read of the beach conditions. From here we move on to the more individualized narratives: of losses that can scarcely be felt or acknowledged (a ‘siren’ singing of her deceased husband—drowned off just such a beach); a preening (more than doting) mother rhapsodizing (in pared-down fashion) about her accomplished (or at least well-traveled) child; a workaholic’s (her husband?) ode to exhaustion (which has a kind of stamped-out wheeze that fits both the tune and the character)—while the ensemble as a whole reminds themselves to keep their children close.

The Lithuanian ensemble that has put this musical and theatrical vessel together (consisting of Lapelytė, the librettist, Vaiva Grainytė, and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė) has very consciously set off this beachscape of human flotsam against the almost clinical view of its audience. If we enter and assemble around the gallery as if in a church choir, our view, gazing down into this vessel of near white light mitigated only by the swimsuits and flesh tones of the performers, is not unlike that of a surgical operating theatre. (Hard not to be conscious of just how close we are to something which in the not-too-distant future may resemble a coroner’s autopsy. The lighting was high-noon beach-bright; fortunately, my photo-sensitive eyes made it through without sunglasses.) As the audience begins to take the measure of this landscape—both physical and psychological—the tone (both musical and emotional) begins to shift slightly to the interior landscapes at some distance from the staged actuality—towards dream, towards irony. Yet within this operating theatre, even this ‘dream’ musing has an aspect of hard realism.

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

The creators have not left us bereft of beach amusements—not excluding the aforementioned pets. Between a trio of beachgoers playing catch, a gorgeous German Shepherd wanders on and off and across the set, beautifully adroit, and a welcome distraction from the unavoidably somber cast of the libretto. (I don’t think the dog barked once; nor, contrary to a “Song of Complaint” (“What’s wrong with people? / They come here with their dogs / Who leave shit on the beach….”) did s/he leave any digestive souvenirs in the sand.) Fair warning to theatrical creators and designers not to sweat the odd canine or feline ‘ad-libs’, but rather their more likely upstaging of the very scenes or material in which they’re intended to merely add or support a reference point. Although one of the remarkable aspects of the performance is the singers’ delivery of some of the songs and arias while lying down, other performers were in constant movement across the stage. Two performers manage to keep up a badminton rally remarkably well.

But the songs (and singing) added their own color—more frequently in the higher, soprano registers. (Philip Glass’s influence seems increasingly pervasive as the opera unfolds, and especially in the middle sections of the opera.) And color is what is increasingly evoked—not the phosphorescence of a healthy sea, but the unnatural or unseasonal colors and atmospheric conditions of an aquatic habitat under dire threat. Catastrophic human incident merely underscores human puniness in the face of planetary collapse. The music finally takes on the aspect of almost existential despair leading up to what finally becomes a soaring lamentation of anticipated absorption into an aquatic necropolis that renders our own human memorials pathetic and absurd.

And so (as Sonny and Cher once sang) the beat goes on. Will we continue to sing after the apocalypse? I feel neither happiness nor sadness in saying we almost certainly will. Less certain is whether we will work in quite the same ways leading up to it and in its aftermath (though biochemists, archaeologists and toxicologists are sure to have their work cut out for them). Will we fly or even move around the way we have over the last century or so? Hard to say; but—with Nico on my mind, as she has been off and on over the last few weeks (more on that for another post)—I would say we will continue to wander. (I heard her harmonium wheeze as much as, say, Fauré, through the show’s more ecclesiastical passages.)

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that other iconic “Beach” drama of the apocalypse may have put its finger on the point more precisely: “There is still time….” until there is no time at all.

Autopsy or new Arcadia? Sun & Sea has less to do with what we may expect from art (or the sea) in decades to come, and more to do with what we may take from love, family, friendship and relationships outside these domains in this anticipated dark age. But then why shouldn’t we try to imagine a post-apocalyptic world in which civility and civil discourse are still possible? The alternative is…. well, actually not unimaginable—which is why even those of us unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to a ‘call of duty’ may feel compelled to insist upon a more militant or prosecutorial approach to human environmental predations in the pre-apocalyptic here-and-now. The shooting script for that other iconic “Beach” drama of the apocalypse may have put its finger on the point more precisely: “There is still time….” until there is no time at all.

0 Comments