Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Doug Aitken

-

Sometime between the morning of November 9th and the current holiday season, there was an interruption in the more or less weekly postings in this space. It’s not like it’s never happened before. I do drop out of sight now and again; and there are those intervals when I’m between destinations (or already there) and the wi-fi connections seem to vanish in some cloud that isn’t The Cloud. Except that AWOL wasn’t really AWOL, in the usual sense. Sometime between the 9th and the 10th, AWOL had gone into a kind of shock. It was sort of like waking up after a black-out drunk episode and slowly reconstructing the events of the previous evening and figuring out what might have happened in the ‘blacked-out’ bits; going over the narrative meticulously, only to arrive at a climax and ending that simply could not have happened. I think this might have happened three or four times in the first 24 hours, usually punctuated by severe nausea. (Hey that can happen after a black-out drunk night.) Over the succeeding month or so, I went through any number of days that began in anxiety, fear and anger (never a great way to start the day), periodically interrupted by ‘bubbles’ of denial from which I would emerge into a slightly dotty déja vu state – ‘oh, right…. It’s the same fright show it was two hours ago, right.’ Except of course it wasn’t – because with each fresh announcement, appointment, tweet from the Perp-Elect or his designated henchman or hench-wench, it seemed to just get scarier. And so it goes – as Linda Ellerbee once used to say.

Sometime between the morning of November 9th and the current holiday season, there was an interruption in the more or less weekly postings in this space. It’s not like it’s never happened before. I do drop out of sight now and again; and there are those intervals when I’m between destinations (or already there) and the wi-fi connections seem to vanish in some cloud that isn’t The Cloud. Except that AWOL wasn’t really AWOL, in the usual sense. Sometime between the 9th and the 10th, AWOL had gone into a kind of shock. It was sort of like waking up after a black-out drunk episode and slowly reconstructing the events of the previous evening and figuring out what might have happened in the ‘blacked-out’ bits; going over the narrative meticulously, only to arrive at a climax and ending that simply could not have happened. I think this might have happened three or four times in the first 24 hours, usually punctuated by severe nausea. (Hey that can happen after a black-out drunk night.) Over the succeeding month or so, I went through any number of days that began in anxiety, fear and anger (never a great way to start the day), periodically interrupted by ‘bubbles’ of denial from which I would emerge into a slightly dotty déja vu state – ‘oh, right…. It’s the same fright show it was two hours ago, right.’ Except of course it wasn’t – because with each fresh announcement, appointment, tweet from the Perp-Elect or his designated henchman or hench-wench, it seemed to just get scarier. And so it goes – as Linda Ellerbee once used to say.I’m operating less in a ‘bubble’ and more of a ‘back-burner’ mode lately – the truly insane reality is always in the background (and on the front pages); but I’m trying to limit my focus on it to those morning and (usually) late afternoon moments with the newspapers and/or on-line and radio news. In the meantime, we have to try to get on with our lives; re-think, reformulate, mobilize, strategize and resist, resist, resist the drift towards ‘normalization’ which inevitably finds its way to front pages and broadcast news. And a lot can happen in 20 days.

For the moment, I’m going to go back to where I was in those 48 or 72 hours before November 8th. I was looking back then, too – though as a way to gauge how we might move forward – not necessarily with the hopeful, almost optimistic spirit I found so striking in the watershed moment I was taking stock of in those pre-election days, but with a view to how we might reframe and refocus conversations – not only about art, but about the culture, the disruptions and displacements wrought by new technologies, transformed economies and commercial models, and the tattered political ethos that seemed further challenged by social and economic inequities, institutional incapacity and environmental degradation. The anxieties remain the same; but also, I think, a slender hope. I’ll try to pick up where I left off when I come to that singular ‘moment,’ when I was just finding my way into the L.A. art world (and out of town at that)….

For the moment, I’m going to go back to where I was in those 48 or 72 hours before November 8th. I was looking back then, too – though as a way to gauge how we might move forward – not necessarily with the hopeful, almost optimistic spirit I found so striking in the watershed moment I was taking stock of in those pre-election days, but with a view to how we might reframe and refocus conversations – not only about art, but about the culture, the disruptions and displacements wrought by new technologies, transformed economies and commercial models, and the tattered political ethos that seemed further challenged by social and economic inequities, institutional incapacity and environmental degradation. The anxieties remain the same; but also, I think, a slender hope. I’ll try to pick up where I left off when I come to that singular ‘moment,’ when I was just finding my way into the L.A. art world (and out of town at that)….: : : : :

As the country goes to the polls and Artillery prepares to celebrate its 10th anniversary (would it be too presumptuous to claim to be some part of the ‘Obama legacy’ that needs to be sustained into the next Presidential administration?), it’s hard to resist a long and slightly wistful look back – conscious of the still larger shadow of history looming over one’s limited generational perspective. It’s impossible, almost inconceivable to take stock of everything that has led to this point both politically and culturally; almost impossible to point to any single factor that shifted the direction of our thinking and broader perspective. It’s harder still to reconcile that perspective with a significant part of the culture that seems to stand on the other side of a distorted two-way mirror; and difficult to ignore the aspects of our political and cultural reality that have led us to what cannot be called anything but a very bitter divide, if not the precipice of a neo-fascist political order. I’m too exhausted to be really angry; and beyond casting my vote and encouraging others to do the same, hesitant to commit to a political movement other than saving the planetary biosphere – the foundation of everything we have.

Artists will probably go on making manifestos for as long as they make art, but it’s impossible not to distrust almost any purported avant-garde manifesto on its face. The notion of an ‘avant-garde’ seems itself almost meaningless in a time when the art being made seems to reach in every conceivable direction, including the overlooked past; and spatial, temporal and imaginary dimensions unique to the individual artist. My favorite of the most recent crop is probably Grayson Perry’s 2014 Red Alan’s – ‘Red Alan’ being the ceramic sculpture of his own childhood teddy bear, ‘Alan Measles.’ (Makes sense to me – but then visitors to my bed would encounter not only my teddy, but a plush chocolate lab.) It’s certainly the most practical. Consider Item No. 2: “Failed paintings to be sent to DISASTER zones to be used to make tents.” Goddess only knows there are enough of them both.

The exclusionary micro- and macro-aggressions of so many of the manifestos of the 20th century seem almost beside the point when that point is not merely to articulate and privilege a place for a certain kind of art or art-making, but to build a world and conversation around it, to amplify and expand its possibilities and possible domains – in short to change the way we see, talk about, and make sense of the world.

There have been many fairs and biennials since I started writing for the magazine (and as long-time readers of the blog are aware, AWOL began as a fair/biennial blow-by-blow). But looking back, one in particular stands out – some five years before Artillery began – not simply for its quality (which may still be unsurpassed), but for its historical moment and everything it stood for at the time. It was a rare moment of optimism both for the larger art world and the Los Angeles art world in particular (and I give it some credit for underscoring that new reality). Closing out her stint at a well-known zine, my editor had sent me to a biennial, being curated by a writer, critic and all-round culture guru we both adored. The writer was Dave Hickey, a frequent contributor to what was then probably my favorite L.A. magazine, Art issues (which also featured a regular column by Doug Harvey, Skipping Formalities); and the biennial was SITE Santa Fe’s fourth, Beau Monde: Toward A Redeemed Cosmopolitanism.

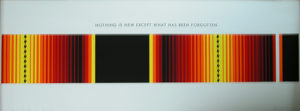

Beau Monde staked out a very idealistic ground. Above and beyond everything else, before pointing or prognosticating in any specific direction (although it did in fact make a kind of speculative projection towards a certain open-ended view of where western contemporary art might be headed), it privileged a kind of conversation that up to that point had rarely been seen in the contemporary world. It was no accident that the show had been meticulously designed (by the Graft firm from Silver Lake), that the movement and rhythm of the space had been as deliberately (and comfortably) plotted out; that the vibratile Jennifer Steinkamp digital installation that ushered the audience into the space would be immediately answered by Alexis Smith’s elevated ‘salon’ with its flaming Ruscha-esque American Southwest sunset skies, repeated in the rich reds, yellows, amber and black striations (oxygenated with a bit of white) in the rug that covered the elevated platform of her installation space. Smith’s sky was inscribed with the legend, “Heaven for weather. Hell for company,” which might be interpreted literally – reflecting the physical beauty of its Santa Fe, New Mexico location; but might also be interpreted more ambiguously. The line is a paraphrase of a famous Mark Twain bon mot (he used several variations of it throughout his career) – implying that heaven would not in all likelihood be his social priority; that (as usual) the cool kids as might be cordoned off into a separate smoking section – in hell.

Hickey had already formed an idea of the kind of biennial exhibition he wanted and most of the artists who might be curated into it before he set to work (with his Graft colleagues) plotting out its installation. What he wanted from his artists was pretty much exactly what they were already doing (or had been: two of them were somewhat elderly and one (Hammersley) was in fact deceased); and he could trust them to deliver. But Smith’s piece was one of the few installations specifically commissioned by Hickey for the show; and although its slight elevation off the floor of SITE’s rehabbed (and Graft-transformed) industrial space dampened its impact, its point was made. This would not simply be a themed biennial, but a series of conversations that gave presence and substance to that theme – the stuff that might actually create and re-create that ‘beau monde.’ And even as Smith’s ‘statement’ piece was set apart, you quickly sensed its echoes – e.g., in the large Bridget Riley painting not quite directly across from it – a blue/yellow, pink/green beribboned abstraction (a kind of self-conscious interrogation and reconsideration of her own ‘Op-Art’ style); even in the Steinkamp digital waves only just traversed.

Hickey had already formed an idea of the kind of biennial exhibition he wanted and most of the artists who might be curated into it before he set to work (with his Graft colleagues) plotting out its installation. What he wanted from his artists was pretty much exactly what they were already doing (or had been: two of them were somewhat elderly and one (Hammersley) was in fact deceased); and he could trust them to deliver. But Smith’s piece was one of the few installations specifically commissioned by Hickey for the show; and although its slight elevation off the floor of SITE’s rehabbed (and Graft-transformed) industrial space dampened its impact, its point was made. This would not simply be a themed biennial, but a series of conversations that gave presence and substance to that theme – the stuff that might actually create and re-create that ‘beau monde.’ And even as Smith’s ‘statement’ piece was set apart, you quickly sensed its echoes – e.g., in the large Bridget Riley painting not quite directly across from it – a blue/yellow, pink/green beribboned abstraction (a kind of self-conscious interrogation and reconsideration of her own ‘Op-Art’ style); even in the Steinkamp digital waves only just traversed. But nowhere did you sense that vibratile dialectic more than in the gallery where Hickey paired Ellsworth Kelly’s four irregularly rectilinear and skewed panels rotating just so, Blue Black Red Green, with Ken Price’s morphous, pulsating, almost fluorescently glazed ceramic sculptures – a conversation you could almost swear, emerging from the gallery, was substance-enhanced. (The picture here in no way does justice to the drama of the installation.) There were cooler zones, too – e.g., Josiah McIlhenny’s cool white tribute to Adolph Loos.

But nowhere did you sense that vibratile dialectic more than in the gallery where Hickey paired Ellsworth Kelly’s four irregularly rectilinear and skewed panels rotating just so, Blue Black Red Green, with Ken Price’s morphous, pulsating, almost fluorescently glazed ceramic sculptures – a conversation you could almost swear, emerging from the gallery, was substance-enhanced. (The picture here in no way does justice to the drama of the installation.) There were cooler zones, too – e.g., Josiah McIlhenny’s cool white tribute to Adolph Loos. If you’re getting the sense that pleasure itself was privileged here, you’re not far off. Hickey (like me) is a beauty freak unembarrassed to wear that bias on his sleeve. But Beau Monde went beyond even those aesthetic parameters to approach something on the order of music, of dance, of play. No accident here that Steinkamp had teamed with Jimmy Johnson, who created music for the installation. By the time the viewer reached Jessica Stockholder’s slightly dystopic installation, s/he might be dancing. In that regard, too, the biennial was highly influential. Whether acknowledged or not, the most important museum (and for that matter some major gallery) exhibitions cannot today be considered fully, much less successfully, installed without consideration for the sheer pleasure of the experience. (LACMA gets this in spades; and Philippe Vergne just took the Geffen to this level with the Doug Aitken Electric Earth mid-career retrospective.)

If you’re getting the sense that pleasure itself was privileged here, you’re not far off. Hickey (like me) is a beauty freak unembarrassed to wear that bias on his sleeve. But Beau Monde went beyond even those aesthetic parameters to approach something on the order of music, of dance, of play. No accident here that Steinkamp had teamed with Jimmy Johnson, who created music for the installation. By the time the viewer reached Jessica Stockholder’s slightly dystopic installation, s/he might be dancing. In that regard, too, the biennial was highly influential. Whether acknowledged or not, the most important museum (and for that matter some major gallery) exhibitions cannot today be considered fully, much less successfully, installed without consideration for the sheer pleasure of the experience. (LACMA gets this in spades; and Philippe Vergne just took the Geffen to this level with the Doug Aitken Electric Earth mid-career retrospective.) You can dance with this, you can move with it (Darryl Montana’s Mardi Gras costumes even seemed to suggest a suitable sartorial accompaniment – a brilliant grace note to Hickey’s show) – the exhibition seemed to reverberate with this implicit message at every turn; or just hang out for a bit – as the couches on the periphery of the Stockholder installation invited us to do. This was an extension of another familiar Hickey preoccupation and critical criterion, really a linchpin of so much of his writing – the social space of art. This was never exactly a new phenomenon; but it was Hickey who drew special attention to its role, not merely in creating the ‘aura’ of an artwork, not merely in its capacity to animate the physical and/or cultural space around it, but the attention (or distraction) and dialogue of viewers around it – how that level of social engagement and its ancillary conversations themselves might contribute to and enrich the critical evaluation of the work of art. For Hickey, the significance of such social/spatial/temporal aspects are magnified in recent decades and have become critical factors in the evaluation of contemporary art.

You can dance with this, you can move with it (Darryl Montana’s Mardi Gras costumes even seemed to suggest a suitable sartorial accompaniment – a brilliant grace note to Hickey’s show) – the exhibition seemed to reverberate with this implicit message at every turn; or just hang out for a bit – as the couches on the periphery of the Stockholder installation invited us to do. This was an extension of another familiar Hickey preoccupation and critical criterion, really a linchpin of so much of his writing – the social space of art. This was never exactly a new phenomenon; but it was Hickey who drew special attention to its role, not merely in creating the ‘aura’ of an artwork, not merely in its capacity to animate the physical and/or cultural space around it, but the attention (or distraction) and dialogue of viewers around it – how that level of social engagement and its ancillary conversations themselves might contribute to and enrich the critical evaluation of the work of art. For Hickey, the significance of such social/spatial/temporal aspects are magnified in recent decades and have become critical factors in the evaluation of contemporary art. It puts a slightly different spin on Jasper Johns’ wry 1967 commentary, The Critic Sees. We do in fact look and see with mouths wide open and tongues frequently moving at full throttle. For that matter, maybe the spectacle frames have some influence on the process. Nothing wrong with any part of it as long as we feel free to put it all into reverse and contradict ourselves, or look at (and talk about) it from another angle. I sometimes wonder if Hickey’s true philosophical antecedents aren’t closer to Oscar Wilde than to Charles Sanders Pierce or William James. (There was certainly some theatricality in evidence in some of the sections of that show – e.g., the aforementioned Kelly/Price gallery, the Murakami ‘balloon’ in its slightly liturgical niche, ready for its ascension.) But Hickey also seemed to be nudging us in the direction of what these objects and installations might become (consider the dramatic tension between the Prices and Kellys, the possibly ‘combustible’ product between the two); where they might take us – which is after all the essential point of this kind of exhibition. The ‘Johns-ian’ footnote to this would be that this might simply be another way of describing the way we encounter all works of art – the way an art object plays upon our perceptual faculties, and our experience and memory of the encounter.

It puts a slightly different spin on Jasper Johns’ wry 1967 commentary, The Critic Sees. We do in fact look and see with mouths wide open and tongues frequently moving at full throttle. For that matter, maybe the spectacle frames have some influence on the process. Nothing wrong with any part of it as long as we feel free to put it all into reverse and contradict ourselves, or look at (and talk about) it from another angle. I sometimes wonder if Hickey’s true philosophical antecedents aren’t closer to Oscar Wilde than to Charles Sanders Pierce or William James. (There was certainly some theatricality in evidence in some of the sections of that show – e.g., the aforementioned Kelly/Price gallery, the Murakami ‘balloon’ in its slightly liturgical niche, ready for its ascension.) But Hickey also seemed to be nudging us in the direction of what these objects and installations might become (consider the dramatic tension between the Prices and Kellys, the possibly ‘combustible’ product between the two); where they might take us – which is after all the essential point of this kind of exhibition. The ‘Johns-ian’ footnote to this would be that this might simply be another way of describing the way we encounter all works of art – the way an art object plays upon our perceptual faculties, and our experience and memory of the encounter. There is the object – itself the product of this kind of transformation (‘take an object; do something to it; do something else to it’); our experience of it, and our conversation around it – both expanding over time; and finally ‘placing’ us in a new, slightly altered space – perceptually, conceptually, culturally. Whether artists actually create a beau monde or take us to it, they certainly give us some navigational tools, and ideas about improvising new ones. The ‘beautiful world’ is no less intimidating for its beauties, its transformations. It may be yet another circle of hell – but as Alexis Smith’s Santa Fe ‘salon’ implied, it just might be the place you want to be.

I’ve had some time to think further on that vision of a beau monde in the weeks since the United States took its great flying leap towards un monde où il ne ferait jamais beau – and certainly fresh hells seem to be opening every day. Whether the planetary biosphere, much less U.S. citizens, can withstand this government’s promised assault will not be known for a few years. But as Johns and all great artists remind us, an object and the world around it can change in the time we’re looking at it. There are no walls or barriers that can impinge upon our ability to look, alter, reconfigure, reshape, exchange, revisit, and revise views (or plead for new ones), and utterly transform those worlds – or transport us to new ones. I don’t necessarily think we need to leave the planet to find them – though I wouldn’t try to deter Elon Musk or Richard Branson or anyone else from trying. But while we’re still here, I’m hoping L.A.’s best artists – and the world’s – keep taking us to the farthest edges of their imaginations. If the political and cultural status quo present us with a reality where the very notion of ‘norm’ is effectively shattered (or certainly mocked – as it is on an almost daily basis in broadcast media), there is nothing to hold them back.

I loved that the special edition print Alexis Smith produced for Beau Monde – a kind of digitized rendition of her installation’s serape-like rug, was captioned, “NOTHING IS NEW EXCEPT WHAT HAS BEEN FORGOTTEN.” The phrase is actually taken from one of Marie-Antoinette’s often witty retorts to her opponents (and later, her jailers) and reads as fresh and timely today as Smith’s ‘heaven and hell’ citation for her salon installation. “Il n’y a de nouveau que ce qui est oublié.” As newspaper front pages and websites fill with what has been effectively “forgotten” by the grotesques and gargoyles gnawing away (willfully or unconsciously) at their own platforms, it is the artists who will be charged with filling the void with actual news – and I hope to be here reporting some of it.

-

‘Are the stars out tonight?’ Harmonic convergence for a new art season

The beginning of another arts and culture season also marks a point where we really start to feel the impact of everything we’ve been experiencing over the preceding orbital/calendar year and start to take its measure. Events move swiftly; you can feel as if you’re stepping onto a speeding train just leaving your apartment; and to miss an event in one’s agenda, or just a day’s news can make you feel as if you’ve missed a station. Our connection to the everyday realities can seem so fragile, so contingent; yet that connection, those realities are themselves being continuously redefined and renegotiated. We need to make course adjustments, reorient the compass, re-navigate. We’re looking forward to the new – thrilled by the possibility of fresh ideas, sensations, beauties (and maybe a little desperate?); taking charge of the negotiations; but it helps to make sense of where we’ve been. (Then again – do we ever really know?)

This year, the best of the first major fall museum exhibitions and gallery solo shows collide, converge, fuse and spark to give us a hint of resonance, new direction, fresh looks at things we might have missed or overlooked, as well as those elements of course correction and perspective that always need to be refreshed.

We get more than a hint of resonance with Doug Aitken’s mid-career retrospective, Electric Earth, which (with MOCA Director, Philippe Vergne’s unstinting and hands-on commitment) practically makes MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary over into a resonant vessel of sight and sound. For Aitken’s show, the Geffen – which has never looked better – is splayed out into an open maze of almost 20 years of Aitken’s architectural/sculptural/experiential multi-screen installations, along with various photographs, lightboxes, collages, sculptures or other objects that offer a kind of emblematic road map to Aitken’s process, a connective tissue that invite the viewer to ‘walk this way.’ Vergne has reconfigured and plotted out the space to parallel Aitken’s process, with its infinite expansion or compression of the moment, convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, and sense of harmonic decay.

I thought the passage in Vergne’s catalogue commentary, expanding on Aitken’s [film] editorial process, summed up both his own installation strategy and Aitken’s fundamental approach: “ … a visual and temporal space conceived to suggest the expectation of narrative order, a tension toward ‘what comes next,’ a dynamic that is endlessly pointing forward giving rise to an open form – improvised and interfaced with thematic relations between sounds and images that strategically dissolve and reconstitute a visual, time-based, and harmonic landscape. This sense of pacing, of interrupted moments, of shifting and floating is simultaneously a summary of a narrative and the negation of that narrative.”

This is the museum exhibition as immersive experience; and the viewer floats away from it ready for pretty much anything that follows. Assuming you’re not spent from the experience (and pace yourself – you may need more than one), you might segue over to Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel for a museum-level exhibition of the work of the Austrian artist, Maria Lassnig, surveying in 31 paintings almost the entire span of her long and diverse career – a kind of prismatic kernel of the major retrospective of her work that appeared at the Tate Liverpool this summer and will soon travel.

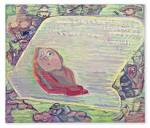

This is the museum exhibition as immersive experience; and the viewer floats away from it ready for pretty much anything that follows. Assuming you’re not spent from the experience (and pace yourself – you may need more than one), you might segue over to Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel for a museum-level exhibition of the work of the Austrian artist, Maria Lassnig, surveying in 31 paintings almost the entire span of her long and diverse career – a kind of prismatic kernel of the major retrospective of her work that appeared at the Tate Liverpool this summer and will soon travel. Maria Lassnig is quite simply the greatest painter you’ve never heard of – except you actually may have, in recent years anyway, only to … well, … push her off the radar again. Lassnig finally began to achieve the recognition she deserved in the last quarter of her career; but her growing audience had really only the barest clue of her daunting scope. The Tate curators – and here in L.A., Lassnig Foundation Chairman, Peter Pakesch and our own Paul Schimmel – have done us all the favor of seizing upon the breadth of this extraordinary career and unfolding its varied objectives and mechanisms of inquiry, its approaches to media, its psychology and overall consciousness, sheer mystery and abundant humanity, into a kind of compact narrative of the artist’s life that, spread out through only five beautiful galleries, is quietly breathtaking.

Maria Lassnig is quite simply the greatest painter you’ve never heard of – except you actually may have, in recent years anyway, only to … well, … push her off the radar again. Lassnig finally began to achieve the recognition she deserved in the last quarter of her career; but her growing audience had really only the barest clue of her daunting scope. The Tate curators – and here in L.A., Lassnig Foundation Chairman, Peter Pakesch and our own Paul Schimmel – have done us all the favor of seizing upon the breadth of this extraordinary career and unfolding its varied objectives and mechanisms of inquiry, its approaches to media, its psychology and overall consciousness, sheer mystery and abundant humanity, into a kind of compact narrative of the artist’s life that, spread out through only five beautiful galleries, is quietly breathtaking.

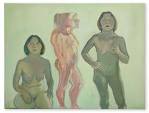

Grounded in a figurative tradition informed by expressionism, Lassnig veered early into abstraction of varying degrees of painterliness and coolness, but always true to herself and her own artistic investigative spirit. The bodily, performative aspect of her gestural style turned her toward a more distinctly psychological, introspective and body-conscious approach, and her work in the 1960s and 1970s took on a more self-conscious, even surreal cast. Her later work, though cooler in palette and approach, partook of even more intimate, diaristic detail. Her subject is, above all else, consciousness itself – and she is true to it to the end.

Helen Frankenthaler, “Brother Angel” (1983), acrylic on canvas, courtesy Gagosian Gallery Across town, there are two other museum quality surveys – and no less breathtaking. The Gagosian Gallery’s 25 year survey of Helen Frankenthaler’s painting, Line Into Color, Color Into Line, clarifies (with some curatorial help from Yale art historian Carol Armstrong and the eminent writer and curator, John Elderfield) the complex genesis and structural sophistication of work that is occasionally viewed through an over-simplistic ‘color field’ prism. The 18 canvases that span the years 1962 to 1987 demonstrate a complex and evolving dialogue, not merely of drawing/line/design and color in the classic sense, but formal conundrums of the line in two-dimensional color-zoned space; line and/or color and edge; mark, subject and (colored) ground; and depiction and mark-making generally. They’re also, quite simply, gorgeous paintings; and if you’re heading to Gagosian to ‘educate the eye,’ be assured that your eyes will also be satiated with pleasure.

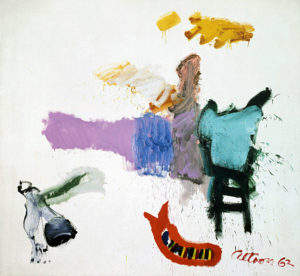

John Altoon, from the Ocean Park series You may experience a sensation of time warp or displacement at the Kohn Gallery’s exhibition of painting and drawing by John Altoon (but then, hey – after the Aitken show, you’re ready for it, right?). ‘Didn’t I just…?’ Sort of – especially if you were at the Altoon retrospective at LACMA in 2014. But rest assured, you’re at Kohn – it’s just that good. Just about everything you would want from an Altoon survey is here, from the more densely abstract paintings (some from the 1950s, some from the 1960s); the commercial pastiches of the early 1960s; the slightly surreal and brilliant color abstractions of the 1960s; the Ocean Park series; those tussles between the abstract and figural that occur throughout; to (finally!) the virtuoso erotic and quasi-sexual farces and fabliaux executed well into the late 1960s. It’s all here – so just go crazy and try not to spend all your money. It’s a commercial gallery, not LACMA, goddamnit!

Okay – so naturally, you’re now thinking of heading to LACMA – and why not? It’s not too far and there two more superb shows that demand your attention: The Serial Impulse at Gemini G.E.L., a 50th anniversary survey, an elegant and compact survey of the classic best of Gemini’s groundbreaking editions; and an absolutely sublime show of 17th century Chinese landscape painting, Alternative Dreams: 17th –Century Chinese Paintings from the Tsao Family Collection.

And now this ‘brief list’ is getting out of hand, so before I break off (to pick up again before the week-end), let me just give you a quick list of the remaining essential shows so far:

Henry Taylor, Blum & Poe, Culver City

Tom Knechtel: Astrolabe, Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverly Hills

Tom Knechtel “The Reader of His Own Self” (do you get the impression we might be going somewhere with this? See, Artillery’s “Pick of the Week” for this week) – with

Mira Schor: “Power” Frieze and War Frieze (1991-94), CB1 Gallery, downtown Los Angeles

Edith Beaucage, Luis de Jesus, Culver City

Ry Rocklen, Honor Fraser, Culver City

Rodney McMillian, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City

Jun Kaneko: Mirage, Edward Cella Art & Architecture, Culver City

And we haven’t even talked about music or theatre (or opera) or movies – or fashion. But we will. Before I go, here’s one thing that’s definitively out of fashion: the Peter Zumthor ‘Gumby’ blob that wants to eat Wilshire Boulevard. Do we have to resurrect Godzilla and Mothra to dispatch this thing? Calling Roger Corman….

Tom Knechtel, “Avery (2)” (2015), ink on paper, courtesy Marc Selwyn Fine Art

Sometime between the morning of November 9th and the current holiday season, there was an interruption in the more or less weekly postings in this space. It’s not like it’s never happened before. I do drop out of sight now and again; and there are those intervals when I’m between destinations (or already there) and the wi-fi connections seem to vanish in some cloud that isn’t The Cloud. Except that AWOL wasn’t really AWOL, in the usual sense. Sometime between the 9th and the 10th, AWOL had gone into a kind of shock. It was sort of like waking up after a black-out drunk episode and slowly reconstructing the events of the previous evening and figuring out what might have happened in the ‘blacked-out’ bits; going over the narrative meticulously, only to arrive at a climax and ending that simply could not have happened. I think this might have happened three or four times in the first 24 hours, usually punctuated by severe nausea. (Hey that can happen after a black-out drunk night.) Over the succeeding month or so, I went through any number of days that began in anxiety, fear and anger (never a great way to start the day), periodically interrupted by ‘bubbles’ of denial from which I would emerge into a slightly dotty déja vu state – ‘oh, right…. It’s the same fright show it was two hours ago, right.’ Except of course it wasn’t – because with each fresh announcement, appointment, tweet from the Perp-Elect or his designated henchman or hench-wench, it seemed to just get scarier. And so it goes – as Linda Ellerbee once used to say.

Sometime between the morning of November 9th and the current holiday season, there was an interruption in the more or less weekly postings in this space. It’s not like it’s never happened before. I do drop out of sight now and again; and there are those intervals when I’m between destinations (or already there) and the wi-fi connections seem to vanish in some cloud that isn’t The Cloud. Except that AWOL wasn’t really AWOL, in the usual sense. Sometime between the 9th and the 10th, AWOL had gone into a kind of shock. It was sort of like waking up after a black-out drunk episode and slowly reconstructing the events of the previous evening and figuring out what might have happened in the ‘blacked-out’ bits; going over the narrative meticulously, only to arrive at a climax and ending that simply could not have happened. I think this might have happened three or four times in the first 24 hours, usually punctuated by severe nausea. (Hey that can happen after a black-out drunk night.) Over the succeeding month or so, I went through any number of days that began in anxiety, fear and anger (never a great way to start the day), periodically interrupted by ‘bubbles’ of denial from which I would emerge into a slightly dotty déja vu state – ‘oh, right…. It’s the same fright show it was two hours ago, right.’ Except of course it wasn’t – because with each fresh announcement, appointment, tweet from the Perp-Elect or his designated henchman or hench-wench, it seemed to just get scarier. And so it goes – as Linda Ellerbee once used to say. For the moment, I’m going to go back to where I was in those 48 or 72 hours before November 8th. I was looking back then, too – though as a way to gauge how we might move forward – not necessarily with the hopeful, almost optimistic spirit I found so striking in the watershed moment I was taking stock of in those pre-election days, but with a view to how we might reframe and refocus conversations – not only about art, but about the culture, the disruptions and displacements wrought by new technologies, transformed economies and commercial models, and the tattered political ethos that seemed further challenged by social and economic inequities, institutional incapacity and environmental degradation. The anxieties remain the same; but also, I think, a slender hope. I’ll try to pick up where I left off when I come to that singular ‘moment,’ when I was just finding my way into the L.A. art world (and out of town at that)….

For the moment, I’m going to go back to where I was in those 48 or 72 hours before November 8th. I was looking back then, too – though as a way to gauge how we might move forward – not necessarily with the hopeful, almost optimistic spirit I found so striking in the watershed moment I was taking stock of in those pre-election days, but with a view to how we might reframe and refocus conversations – not only about art, but about the culture, the disruptions and displacements wrought by new technologies, transformed economies and commercial models, and the tattered political ethos that seemed further challenged by social and economic inequities, institutional incapacity and environmental degradation. The anxieties remain the same; but also, I think, a slender hope. I’ll try to pick up where I left off when I come to that singular ‘moment,’ when I was just finding my way into the L.A. art world (and out of town at that)…. Hickey had already formed an idea of the kind of biennial exhibition he wanted and most of the artists who might be curated into it before he set to work (with his Graft colleagues) plotting out its installation. What he wanted from his artists was pretty much exactly what they were already doing (or had been: two of them were somewhat elderly and one (Hammersley) was in fact deceased); and he could trust them to deliver. But Smith’s piece was one of the few installations specifically commissioned by Hickey for the show; and although its slight elevation off the floor of SITE’s rehabbed (and Graft-transformed) industrial space dampened its impact, its point was made. This would not simply be a themed biennial, but a series of conversations that gave presence and substance to that theme – the stuff that might actually create and re-create that ‘beau monde.’ And even as Smith’s ‘statement’ piece was set apart, you quickly sensed its echoes – e.g., in the large Bridget Riley painting not quite directly across from it – a blue/yellow, pink/green beribboned abstraction (a kind of self-conscious interrogation and reconsideration of her own ‘Op-Art’ style); even in the Steinkamp digital waves only just traversed.

Hickey had already formed an idea of the kind of biennial exhibition he wanted and most of the artists who might be curated into it before he set to work (with his Graft colleagues) plotting out its installation. What he wanted from his artists was pretty much exactly what they were already doing (or had been: two of them were somewhat elderly and one (Hammersley) was in fact deceased); and he could trust them to deliver. But Smith’s piece was one of the few installations specifically commissioned by Hickey for the show; and although its slight elevation off the floor of SITE’s rehabbed (and Graft-transformed) industrial space dampened its impact, its point was made. This would not simply be a themed biennial, but a series of conversations that gave presence and substance to that theme – the stuff that might actually create and re-create that ‘beau monde.’ And even as Smith’s ‘statement’ piece was set apart, you quickly sensed its echoes – e.g., in the large Bridget Riley painting not quite directly across from it – a blue/yellow, pink/green beribboned abstraction (a kind of self-conscious interrogation and reconsideration of her own ‘Op-Art’ style); even in the Steinkamp digital waves only just traversed. But nowhere did you sense that vibratile dialectic more than in the gallery where Hickey paired Ellsworth Kelly’s four irregularly rectilinear and skewed panels rotating just so, Blue Black Red Green, with Ken Price’s morphous, pulsating, almost fluorescently glazed ceramic sculptures – a conversation you could almost swear, emerging from the gallery, was substance-enhanced. (The picture here in no way does justice to the drama of the installation.) There were cooler zones, too – e.g., Josiah McIlhenny’s cool white tribute to Adolph Loos.

But nowhere did you sense that vibratile dialectic more than in the gallery where Hickey paired Ellsworth Kelly’s four irregularly rectilinear and skewed panels rotating just so, Blue Black Red Green, with Ken Price’s morphous, pulsating, almost fluorescently glazed ceramic sculptures – a conversation you could almost swear, emerging from the gallery, was substance-enhanced. (The picture here in no way does justice to the drama of the installation.) There were cooler zones, too – e.g., Josiah McIlhenny’s cool white tribute to Adolph Loos. If you’re getting the sense that pleasure itself was privileged here, you’re not far off. Hickey (like me) is a beauty freak unembarrassed to wear that bias on his sleeve. But Beau Monde went beyond even those aesthetic parameters to approach something on the order of music, of dance, of play. No accident here that Steinkamp had teamed with Jimmy Johnson, who created music for the installation. By the time the viewer reached Jessica Stockholder’s slightly dystopic installation, s/he might be dancing. In that regard, too, the biennial was highly influential. Whether acknowledged or not, the most important museum (and for that matter some major gallery) exhibitions cannot today be considered fully, much less successfully, installed without consideration for the sheer pleasure of the experience. (LACMA gets this in spades; and Philippe Vergne just took the Geffen to this level with the Doug Aitken Electric Earth mid-career retrospective.)

If you’re getting the sense that pleasure itself was privileged here, you’re not far off. Hickey (like me) is a beauty freak unembarrassed to wear that bias on his sleeve. But Beau Monde went beyond even those aesthetic parameters to approach something on the order of music, of dance, of play. No accident here that Steinkamp had teamed with Jimmy Johnson, who created music for the installation. By the time the viewer reached Jessica Stockholder’s slightly dystopic installation, s/he might be dancing. In that regard, too, the biennial was highly influential. Whether acknowledged or not, the most important museum (and for that matter some major gallery) exhibitions cannot today be considered fully, much less successfully, installed without consideration for the sheer pleasure of the experience. (LACMA gets this in spades; and Philippe Vergne just took the Geffen to this level with the Doug Aitken Electric Earth mid-career retrospective.) You can dance with this, you can move with it (Darryl Montana’s Mardi Gras costumes even seemed to suggest a suitable sartorial accompaniment – a brilliant grace note to Hickey’s show) – the exhibition seemed to reverberate with this implicit message at every turn; or just hang out for a bit – as the couches on the periphery of the Stockholder installation invited us to do. This was an extension of another familiar Hickey preoccupation and critical criterion, really a linchpin of so much of his writing – the social space of art. This was never exactly a new phenomenon; but it was Hickey who drew special attention to its role, not merely in creating the ‘aura’ of an artwork, not merely in its capacity to animate the physical and/or cultural space around it, but the attention (or distraction) and dialogue of viewers around it – how that level of social engagement and its ancillary conversations themselves might contribute to and enrich the critical evaluation of the work of art. For Hickey, the significance of such social/spatial/temporal aspects are magnified in recent decades and have become critical factors in the evaluation of contemporary art.

You can dance with this, you can move with it (Darryl Montana’s Mardi Gras costumes even seemed to suggest a suitable sartorial accompaniment – a brilliant grace note to Hickey’s show) – the exhibition seemed to reverberate with this implicit message at every turn; or just hang out for a bit – as the couches on the periphery of the Stockholder installation invited us to do. This was an extension of another familiar Hickey preoccupation and critical criterion, really a linchpin of so much of his writing – the social space of art. This was never exactly a new phenomenon; but it was Hickey who drew special attention to its role, not merely in creating the ‘aura’ of an artwork, not merely in its capacity to animate the physical and/or cultural space around it, but the attention (or distraction) and dialogue of viewers around it – how that level of social engagement and its ancillary conversations themselves might contribute to and enrich the critical evaluation of the work of art. For Hickey, the significance of such social/spatial/temporal aspects are magnified in recent decades and have become critical factors in the evaluation of contemporary art. It puts a slightly different spin on Jasper Johns’ wry 1967 commentary, The Critic Sees. We do in fact look and see with mouths wide open and tongues frequently moving at full throttle. For that matter, maybe the spectacle frames have some influence on the process. Nothing wrong with any part of it as long as we feel free to put it all into reverse and contradict ourselves, or look at (and talk about) it from another angle. I sometimes wonder if Hickey’s true philosophical antecedents aren’t closer to Oscar Wilde than to Charles Sanders Pierce or William James. (There was certainly some theatricality in evidence in some of the sections of that show – e.g., the aforementioned Kelly/Price gallery, the Murakami ‘balloon’ in its slightly liturgical niche, ready for its ascension.) But Hickey also seemed to be nudging us in the direction of what these objects and installations might become (consider the dramatic tension between the Prices and Kellys, the possibly ‘combustible’ product between the two); where they might take us – which is after all the essential point of this kind of exhibition. The ‘Johns-ian’ footnote to this would be that this might simply be another way of describing the way we encounter all works of art – the way an art object plays upon our perceptual faculties, and our experience and memory of the encounter.

It puts a slightly different spin on Jasper Johns’ wry 1967 commentary, The Critic Sees. We do in fact look and see with mouths wide open and tongues frequently moving at full throttle. For that matter, maybe the spectacle frames have some influence on the process. Nothing wrong with any part of it as long as we feel free to put it all into reverse and contradict ourselves, or look at (and talk about) it from another angle. I sometimes wonder if Hickey’s true philosophical antecedents aren’t closer to Oscar Wilde than to Charles Sanders Pierce or William James. (There was certainly some theatricality in evidence in some of the sections of that show – e.g., the aforementioned Kelly/Price gallery, the Murakami ‘balloon’ in its slightly liturgical niche, ready for its ascension.) But Hickey also seemed to be nudging us in the direction of what these objects and installations might become (consider the dramatic tension between the Prices and Kellys, the possibly ‘combustible’ product between the two); where they might take us – which is after all the essential point of this kind of exhibition. The ‘Johns-ian’ footnote to this would be that this might simply be another way of describing the way we encounter all works of art – the way an art object plays upon our perceptual faculties, and our experience and memory of the encounter.

This is the museum exhibition as immersive experience; and the viewer floats away from it ready for pretty much anything that follows. Assuming you’re not spent from the experience (and pace yourself – you may need more than one), you might segue over to Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel for a museum-level exhibition of the work of the Austrian artist, Maria Lassnig, surveying in 31 paintings almost the entire span of her long and diverse career – a kind of prismatic kernel of the major retrospective of her work that appeared at the Tate Liverpool this summer and will soon travel.

This is the museum exhibition as immersive experience; and the viewer floats away from it ready for pretty much anything that follows. Assuming you’re not spent from the experience (and pace yourself – you may need more than one), you might segue over to Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel for a museum-level exhibition of the work of the Austrian artist, Maria Lassnig, surveying in 31 paintings almost the entire span of her long and diverse career – a kind of prismatic kernel of the major retrospective of her work that appeared at the Tate Liverpool this summer and will soon travel. Maria Lassnig is quite simply the greatest painter you’ve never heard of – except you actually may have, in recent years anyway, only to … well, … push her off the radar again. Lassnig finally began to achieve the recognition she deserved in the last quarter of her career; but her growing audience had really only the barest clue of her daunting scope. The Tate curators – and here in L.A., Lassnig Foundation Chairman, Peter Pakesch and our own Paul Schimmel – have done us all the favor of seizing upon the breadth of this extraordinary career and unfolding its varied objectives and mechanisms of inquiry, its approaches to media, its psychology and overall consciousness, sheer mystery and abundant humanity, into a kind of compact narrative of the artist’s life that, spread out through only five beautiful galleries, is quietly breathtaking.

Maria Lassnig is quite simply the greatest painter you’ve never heard of – except you actually may have, in recent years anyway, only to … well, … push her off the radar again. Lassnig finally began to achieve the recognition she deserved in the last quarter of her career; but her growing audience had really only the barest clue of her daunting scope. The Tate curators – and here in L.A., Lassnig Foundation Chairman, Peter Pakesch and our own Paul Schimmel – have done us all the favor of seizing upon the breadth of this extraordinary career and unfolding its varied objectives and mechanisms of inquiry, its approaches to media, its psychology and overall consciousness, sheer mystery and abundant humanity, into a kind of compact narrative of the artist’s life that, spread out through only five beautiful galleries, is quietly breathtaking.