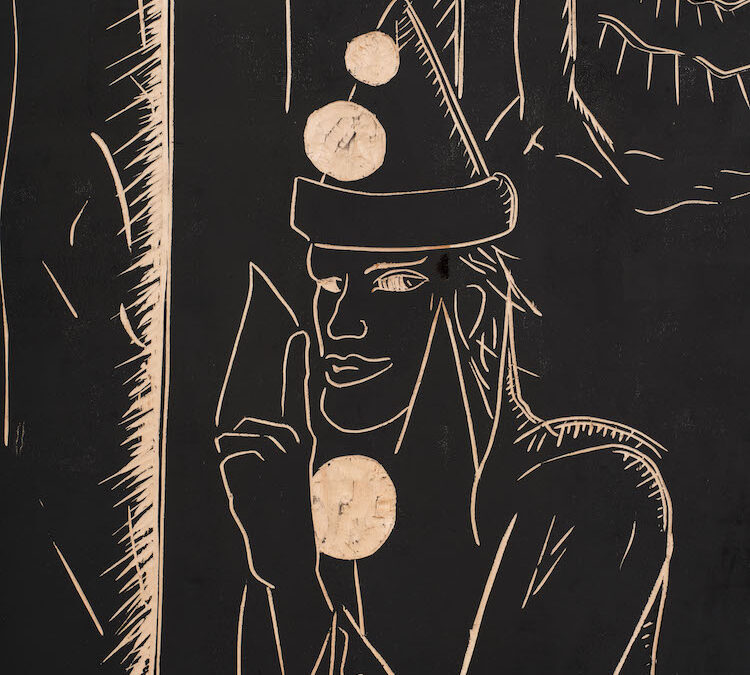

The glittering paintings wouldn’t be out of place in Giza or Athens or Persepolis. RETNA’s bold scripts are the kind that shout down at you from the tops of ancient monuments. Sometimes elements of the painted characters resemble ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs,...