Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: cinema

-

Afrofuture Zombies

Bunker VisionOne of the very positive effects of MTV and YouTube is the restoration of demand for short films. Early cinema consisted mostly of short films. Auteurs of early cinema managed to pack a lot of plot into films that ran 20 minutes or less. MTV also inspired a lot of musicians to try their hand at making films. These films were often short. Many musicians went to art school, so short films by musicians aren’t necessarily vanity projects by celebrities.

Baloji was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo. When he was three his father took him to Belgium without telling his mother. He grew up as an outsider and started performing with a rap group when he was 15. A letter that he received from his mother when he was 26 was a paradigm shifter. It served as inspiration for his first album, which he dedicated to her. His stated goal is to make art that stands the test of time. In 2019 he made his first film. Although his music serves as the soundtrack for it, the film transcends the music video genre.

It opens in a Kinshasa barbershop. The opening lines of the song that provides the soundtrack are sung a cappella by a customer who is getting a haircut. The camera lands on a man walking by the shop in a lurid yellow jacket, and follows him. As he navigates the crowded streets, the jacket keeps our focus on him. He heads across a swarming traffic circle that has as its central feature a sort of robot that directs traffic. (Traffic control robots are an actual thing there.) He arrives in a residential neighborhood as night falls, and everybody’s face is lit up by their cell phones. Tossing off the yellow coat he makes his way up a flight of stairs to a dance club. In the club, everybody is glued to their phone as he sings about “everybody in the spotlight” of their phones. (The song is called “Zombies,” and refers to people becoming mobile phone zombies.) There is a lot of spirited dancing with selfie sticks and VR headsets. The camera lands on a flashy pimp who is partying at the club. One of his ladies gets up to leave.

As she leaves, we get a wonderful instrumental interlude that could have been torn from a Belmondo secret agent movie. She makes her way to the traffic circle wearing bright red so that she is easy to follow, and after crossing it starts to tear off her club clothing, starting with the straight black wig. She arrives home, where her mother appears to have a underground beauty shop in her living room. A young girl is getting an elaborate hair treatment (a sort of ironic Topsy). She explains how many likes she’ll get for it on social media.

Then follows a segment in the courtyard outside which most resembles a music video. It is a fashion show of wild Afrofutristic costumes with characters dancing outdoors. Following this scene comes a parade in the street featuring those costumes and a live brass band. A white man (the only one in the film) is being carried on a litter in a colonial uniform. He is tossing cash to the people watching the parade. In the final shots of the film his bloodied body is carried pieta-style to a dump. As the final melancholy music plays, a giant (a man on stilts) leads a horse (two men in a costume) down a long alley. The credits are a mobile text exchange superimposed on the action. Although this film is made by a musician, it is more of a short film than a music video. Let’s hope that this becomes a trend.

-

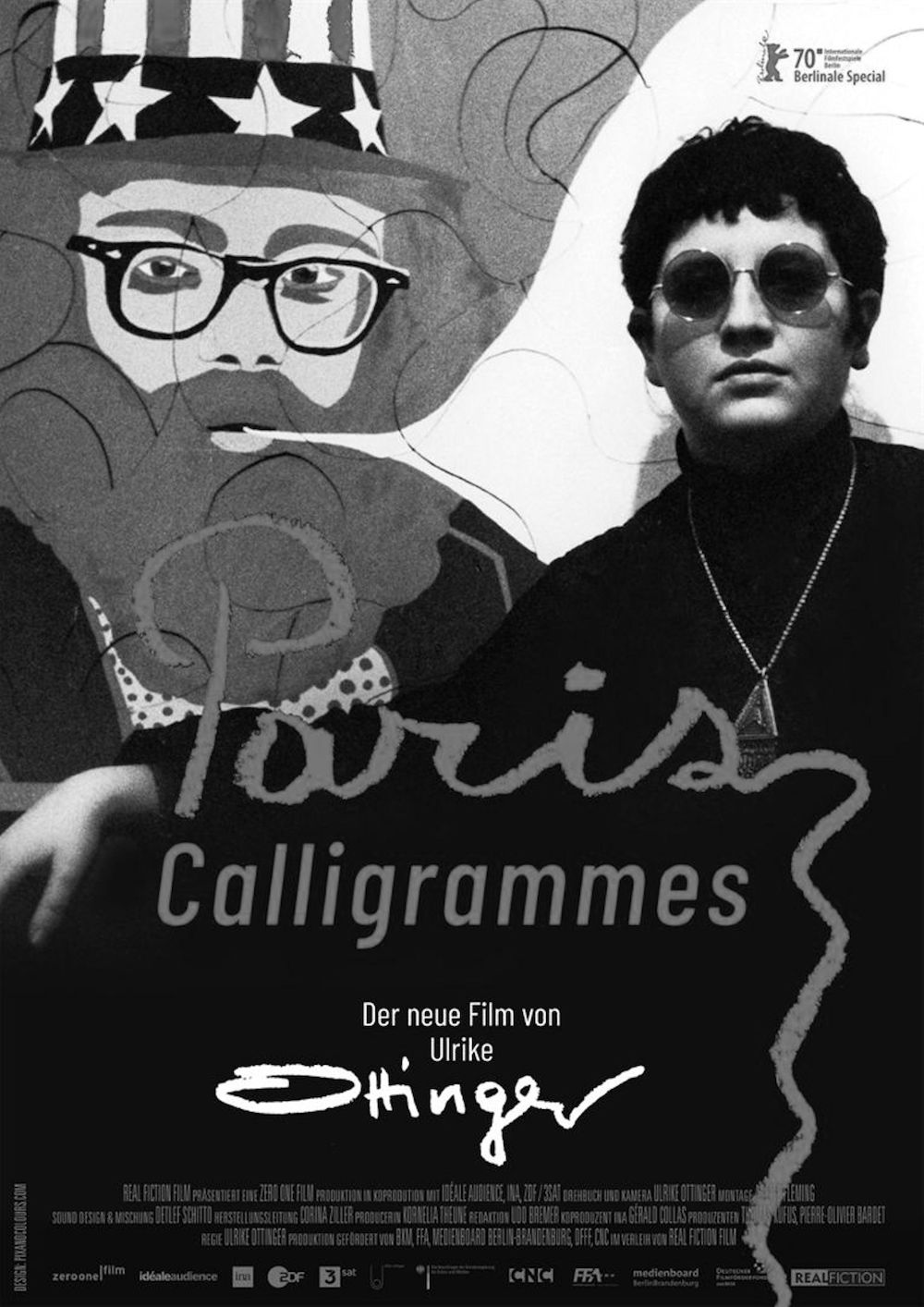

Ottinger for Anglophones

Bunker VisionOne of the things that always made the French New Wave cinema special was that one of the leading figures, Agnes Varda, was a woman. American underground cinema had Maya Deren. But based on what one could find available in the United States with English subtitles, the New German Film movement of the 1970s was an all-male affair. Somehow the films of Ulrike Ottinger never made it to the Anglophone world. This is currently being rectified.

Aside from the usual problems that women face from the male-dominated gatekeepers of the art world, Ottinger’s tendency to hop between disciplines has made it harder to reduce her to an elevator pitch. When The New York Times weighed in, they pronounced that she was “a one-woman avant-garde opposition to the sulky male melodramas of Wenders, Fassbinder and Herzog.” Aside from her gender, there are some other important parallels to Varda. They both produced things that can be shown in museums without projectors.

Ottinger’s father was a painter, and she too started out as a painter; even running a gallery for a while. At one point she was a lithographer, and her photography is well-known on its own merits. When it was most difficult to release her films, she released books about them. The visuals make for wonderful coffee table books. Think Alejandro Jodorowsky without the meanness, or a lesbian Cockettes. All of her movies focus on the female point of view, and her casts mostly consist of women. Ottinger has been out as a lesbian from Day One, and she defies lesbian stereotypes. Among these is the notion that lesbians and camp are mutually exclusive. Even if she shoots a documentary in Mongolia, she has everybody’s finery in its most vivid form. She makes the sort of films that one would expect from a painter.

The best place to start the Ottinger experience is with her most gonzo films. Madam X: an Absolute Ruler is a tale of dissatisfied women throwing off the chains of their daily existences to run away with an all-female pirate ship. She describes Freak Orlando as “a history of the world from its beginnings to our day, including the errors, the incompetence, the thirst for power, the fear, the madness, the cruelty and the commonplace.” This is the one that most frequently draws comparisons to the visual excesses of Jodorowsky. The production values are great by underground movie standards, and one can sense that the lack of big budgets make for a more creative approach.

As Ottinger’s growing renown takes hold, she is getting interviewed more. Many of these interviews (in English or subtitled) have found their way onto YouTube. They are fun to watch because she has such an all-encompassing worldview. Although she currently has no films available on DVD with English subtitles, she is sufficiently well regarded to have been invited to join the Academy of Motion Pictures in 2019. Her most recent work Paris Calligrams (2020) is a collage of formats used in the service of documenting her early years as a painter in Paris. It would not look out of place as an installation in a show of her paintings and photographs. If any curators are looking for an established artist to “discover,” she’s hiding in plain sight.

-

FILM: SECOND ACTS

While sagas of personal transformation are a staple of recent nonfiction filmmaking—from U.N. peacekeeper Roméo Dallaire’s inexorable drift into despair (and back) in the CBC’s Rwanda documentary Shake Hands With the Devil, to crack-mom Kirk White’s unexpected ascent into rehab in the Dickhouse sleaze-fest The Wild and Wonderful Whites of West Virginia—two entries in the 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival take the motif a significant step further. In Tamar Halpern and Chris Quilty’s Llyn Foulkes One Man Band, a contender in the Documentary Competition, and in Josh Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, exhibited as part of festival’s International Showcase, the filmmakers themselves, standing outside the frame but very much part of the picture, take on the role of confessor, facilitating—or in Oppenheimer’s case, guiding—their subjects’ journey toward a deeper appreciation of their human condition and pointing the way forward to one or another species of redemption.

In opening his heart to Halpern and Quilty, for example, artist-musician Llyn Foulkes pushes through to levels of self-understanding that may no longer be available to him qua artist-musician. Over the more than seven years (2004–2012) it took to shoot the film, its subject—who is never less than honest with his interlocutors, and who over time comes to suspect that “artists don’t have effects any more” (see also Auden’s “Poetry makes nothing happen”)—provides ample glimpses into his personal history and studio practices even as his mood shifts from a reflexive sense of injury at the hands of the LA art establishment (“Is it ever going to be my time?”) to a pained acknowledgment of his penchant for self-sabotage (“I’m not very friendly” or “I’m too self-centered”) and a wholesale reassessment of his vocation (“I’ve put art on too high a pedestal” and “I’m tired of being a one-man band”). Meanwhile, the filmmakers’ narrative line takes us from a chronicle of perceived insult and injury, reaching its nadir in the aftermath of 2004’s poorly attended group show at New York’s Kent Gallery (to which Foulkes contributed a single large painting), to one of triumphant vindication, culminating in a 2011 Art in America cover story and in this year’s widely attended, universally lauded career retrospective at the Hammer. (If the show had a metacritic.com rating, it would be somewhere in the high 80s.)

film still from Llyn Foulkes One Man Band As the story line changes, so do the questions raised in the talking-head commentary by curators, critics and other artists, from “Why hasn’t Foulkes achieved the kind of recognition and earning power accorded other Ferus alumni?” to “Is Foulkes finally about to achieve the kind of recognition and earning power accorded other Ferus alumini?” to “Will success spoil—no, make that satisfy—Llyn Foulkes?” “Perhaps!” answer the filmmakers, though not as confidently as that exclamation mark might suggest.

While Llyn Foulkes’ repeated threats to “quit art” if “something doesn’t happen this time” (the art-world equivalent of Eric Cartman’s “Screw you guys, I’m going home!”) may, post-Hammer, seem a case of flogging an already decomposed horse—the slack final third of Halpern and Quilty’s film shares a little of this quality—the end result of all that Sturm und Drang in all the aforementioned movies lies, of course, outside their time frame. Maybe even outside time.

How ephemeral, after all, is the issue of our best intentions? In the case of Anwar Congo, chief among the decidedly inhuman human protagonists of the Danish-British-Norwegian coproduction The Act of Killing, we must suspect the worst. In a surreal variation on the truth-commission process that attained prominence following the fall of South Africa’s apartheid government and during Rwanda’s post-civil-war reconstruction, London-based filmmaker Josh Oppenheimer offered a group of elderly, well-heeled Indonesian thugs who, in the 1960s, were enlisted by the Suharto government to carry out genocide against more than a million Indonesian “communists” the opportunity to stage reenactments of their crimes against humanity—on camera, with a budget, and props, and costumes, and with a mandate to recreate their favorite American film genres! Predictably, gangster films, horror films, and westerns figure prominently, as do Bollywood-style production numbers. And where did Congo and company turn for their extras? To the very neighborhoods and villages they had terrorized 50 years earlier, casting as victims both the children of those they had terrorized, many of them witnesses to the original atrocities, and the hitherto insufficiently traumatized grandchildren of the historical victims, kids who no doubt grew up listening to eyewitness accounts of those same atrocities.

All of which makes for an unbelievably interesting and original documentary—so interesting and original, in fact, that when Werner Herzog and Errol Morris saw early cuts of The Act of Killing, they immediately signed on as executive producers. Which is no surprise, given the levels of weirdness involved. Over and above the already enumerated grotesqueries of Oppenheimer’s film—grotesqueries which shouldn’t, by the way, be mistaken for the point of the exercise—is the fact that the dapper Congo and his less fashion-forward colleagues (one of them with a penchant for cross-dressing) are by no means pariahs in present-day Indonesia.

Quite the contrary. In the minds of many Indonesians—not least of all the members of the paramilitary Pancasila Youth organization to which Congo and his cronies today act as advisors and role models—anti-communism is still, as it was under Suharto, the state religion. For these young fascists, in their inappropriately garish red-and-black camouflage outfits, the old-school perpetrators of so many shootings, garottings and beheadings, to say nothing of their enthusiastically enhanced interrogation techniques—all arguably conducted more for the sake of purging Indonesia of ethnic Chinese than of actual communists—are culture heroes.

And so it goes, until one of those culture heroes—in the interest of adding another dash of spice to his legacy—puckishly announces his intention to play the victim in one of the grislier reenactments. (“Come watch grandpa get tortured and killed!”) That, folks, is the turn of events that puts The Act of Killing firmly in step with the through-line of the report you’ve just finished reading.

THE ACT OF KILLING

A film by Joshua Oppenheimer

On DVD this November.LLYN FOULKES ONE MAN BAND

A film by Tamar Halpern & Chris Quilty

To be released in 2014; check FB page

llynfoulkesonemanband for schedule of college & museum preview screenings.