One of the things that always made the French New Wave cinema special was that one of the leading figures, Agnes Varda, was a woman. American underground cinema had Maya Deren. But based on what one could find available in the United States with English subtitles, the New German Film movement of the 1970s was an all-male affair. Somehow the films of Ulrike Ottinger never made it to the Anglophone world. This is currently being rectified.

Aside from the usual problems that women face from the male-dominated gatekeepers of the art world, Ottinger’s tendency to hop between disciplines has made it harder to reduce her to an elevator pitch. When The New York Times weighed in, they pronounced that she was “a one-woman avant-garde opposition to the sulky male melodramas of Wenders, Fassbinder and Herzog.” Aside from her gender, there are some other important parallels to Varda. They both produced things that can be shown in museums without projectors.

Ottinger’s father was a painter, and she too started out as a painter; even running a gallery for a while. At one point she was a lithographer, and her photography is well-known on its own merits. When it was most difficult to release her films, she released books about them. The visuals make for wonderful coffee table books. Think Alejandro Jodorowsky without the meanness, or a lesbian Cockettes. All of her movies focus on the female point of view, and her casts mostly consist of women. Ottinger has been out as a lesbian from Day One, and she defies lesbian stereotypes. Among these is the notion that lesbians and camp are mutually exclusive. Even if she shoots a documentary in Mongolia, she has everybody’s finery in its most vivid form. She makes the sort of films that one would expect from a painter.

The best place to start the Ottinger experience is with her most gonzo films. Madam X: an Absolute Ruler is a tale of dissatisfied women throwing off the chains of their daily existences to run away with an all-female pirate ship. She describes Freak Orlando as “a history of the world from its beginnings to our day, including the errors, the incompetence, the thirst for power, the fear, the madness, the cruelty and the commonplace.” This is the one that most frequently draws comparisons to the visual excesses of Jodorowsky. The production values are great by underground movie standards, and one can sense that the lack of big budgets make for a more creative approach.

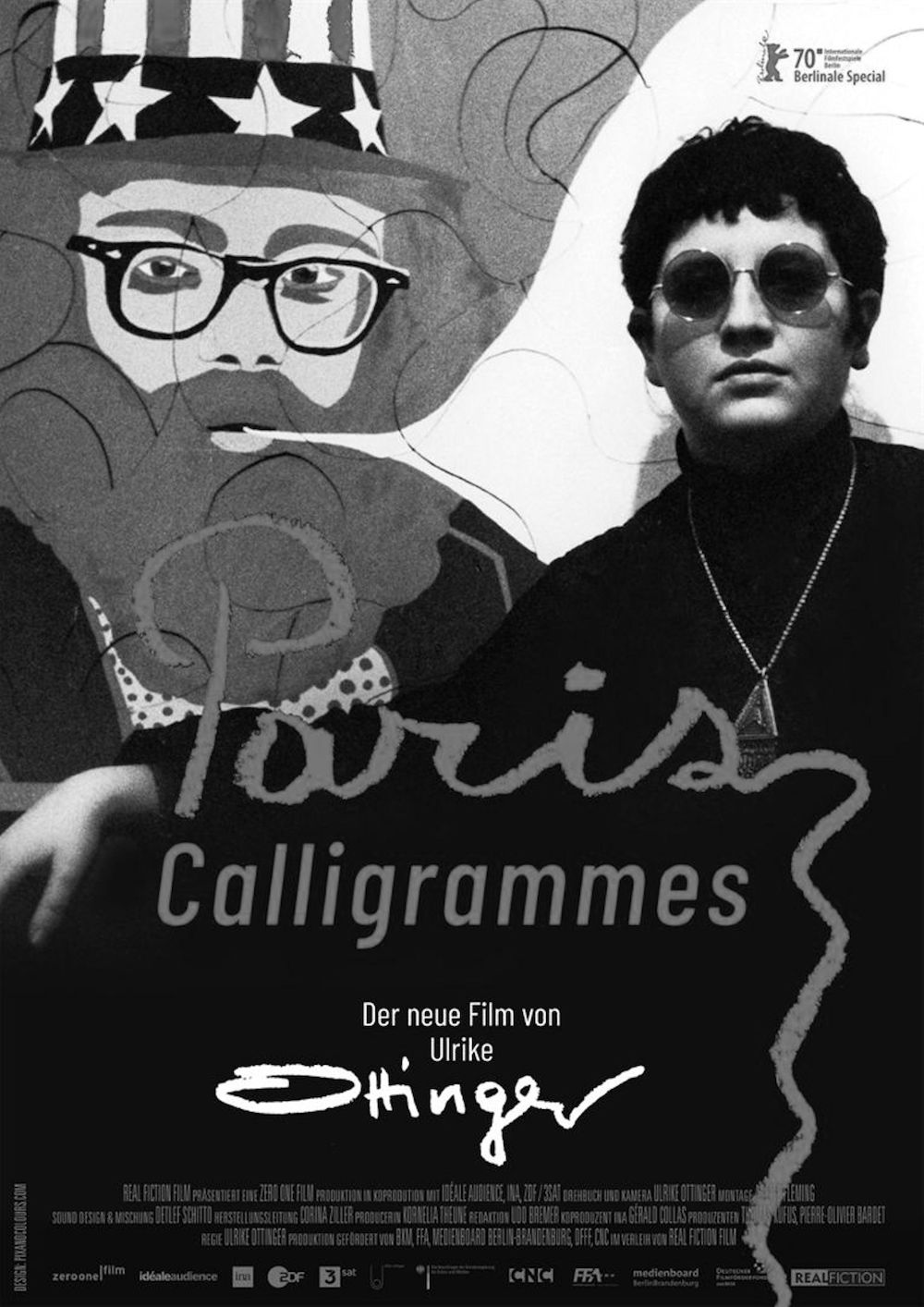

As Ottinger’s growing renown takes hold, she is getting interviewed more. Many of these interviews (in English or subtitled) have found their way onto YouTube. They are fun to watch because she has such an all-encompassing worldview. Although she currently has no films available on DVD with English subtitles, she is sufficiently well regarded to have been invited to join the Academy of Motion Pictures in 2019. Her most recent work Paris Calligrams (2020) is a collage of formats used in the service of documenting her early years as a painter in Paris. It would not look out of place as an installation in a show of her paintings and photographs. If any curators are looking for an established artist to “discover,” she’s hiding in plain sight.