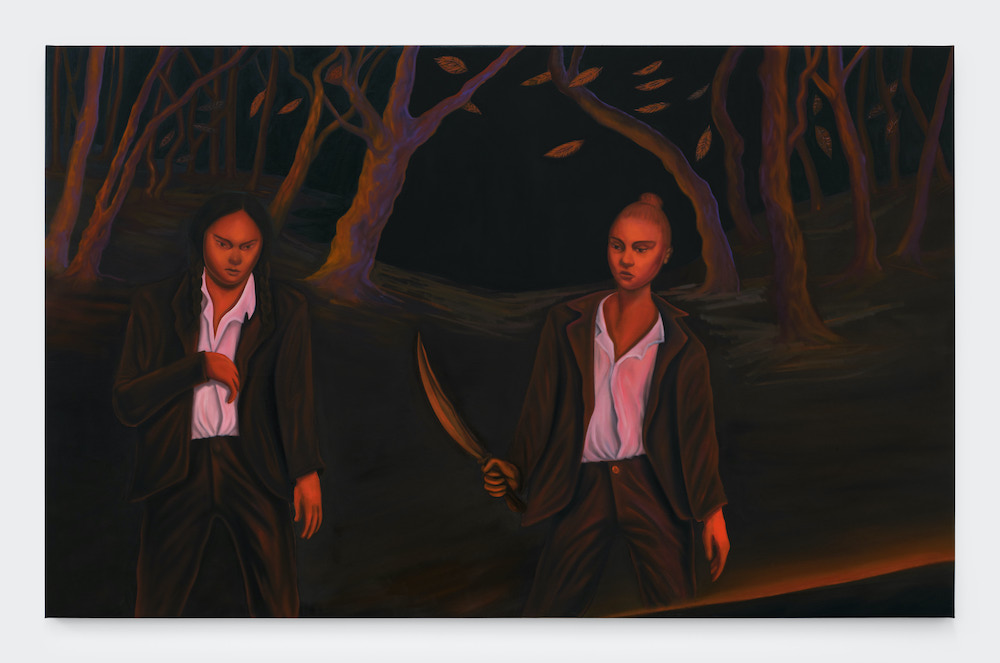

Austin Lee’s haunting soft-focus paintings are what I imagine my nightmares would look like if rendered in claymation and run through an AI algorithm. The artist’s digital/analog hybrids are creepy—a good kind of creepy, my kind of creepy. In the video Starers (2024),...