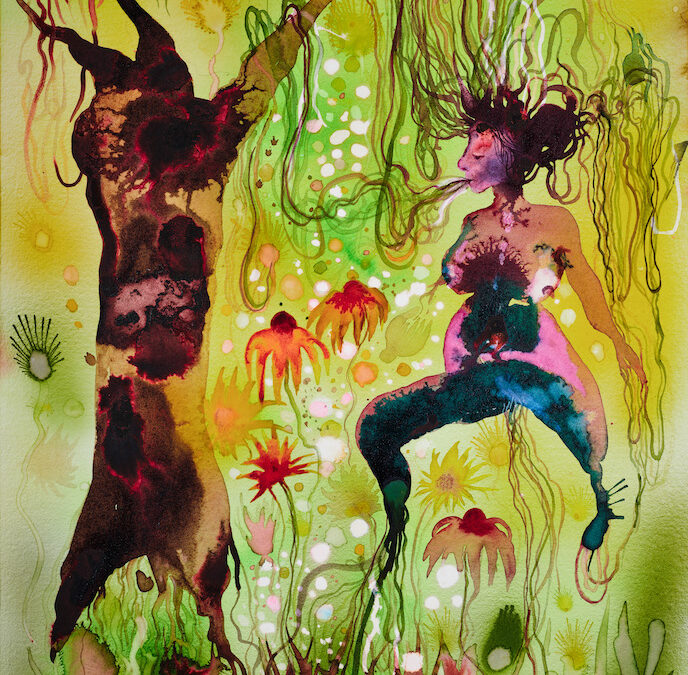

T.J. Dedeaux-Norris had already segued from performance and music to painting and printmaking before completing her MFA at Yale, but she foregrounds the performative aspect of her approach in “Breach of Confidentiality,” her debut solo exhibition at Walter Maciel...