Micol Hebron is an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles. Through photographic works, videos, installations, performance and writing, she has become known for critically engaging the tropes of art history and modernism, with a particular eye toward resurfacing and re-examining feminist activism. Recently, she launched a collaborative poster project called “(en)Gendered (in)Equity,” in which artists create unique and visually dynamic posters depicting the ratio of gender representation at art galleries in LA and beyond. Not surprisingly, the statistics remain less than ideal, with most galleries showing more male artists than female. The project, which had its first exhibition at West L.A. College last fall, has gone viral, attracting nearly 200 participants, and plans are in the works for additional shows. I interviewed Hebron via email to ask her about the genesis, and the future of this project, as well as her thoughts on gender inequity in the art world in general.

ARTILLERY: Recently, the artists Virginia Katz and Michelle Carla Handel hosted a discussion on gender inequity in the arts at Raid Projects. Right as I walked in, you were giving what I thought was a fascinating and useful analysis in which you tied the root causes of sexism in the art world to the capitalist marketplace. Could you perhaps restate your thoughts for Artillery’s readers?

MICOL HEBRON: The paradigm of sexism has been in place, consistently, since the advent of the art world as we know it. The issue is being spotlighted now, however, as we see an aggressive increase in the number, size and prominence of super-galleries, art fairs, and biennials, and that’s because each of these mechanisms are heavily reliant upon capital in order to succeed, and capitalism presents an inherently patriarchal system and structure.

The commercial gallery system that we know today emerged in the late ’60s and ’70s in New York, and in the ’80s in Los Angeles. Prior to this, the art world was largely defined by museums, artist-run spaces and independent collectors. With the increasing commodification of art and artists comes an increase in the attendant problems—and biases—of capitalism. The contemporary gallery system seems to be mirroring the distribution of wealth in the United States—there is a 1% of the gallery world (Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner, Blum & Poe, etc.) that seems to hold the majority of the power, capital and visibility. As many of these galleries are expanding to the size of museums, there is a complicated blurring of the lines between gallery and museum, commercial marketplace and educational forum. It takes a formidable artistic practice to be able to fill (and sell from) one of the super-galleries—and the artists who are capable of doing so typically have large studios and numerous paid assistants. The simple fact is that there are more male artists who are in this position than female artists.

Tell us about the genesis and evolution of the (en)Gendered (in)Equity poster project.

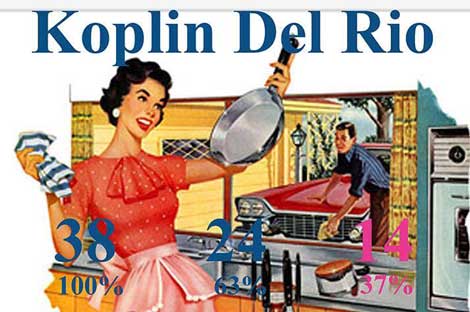

I have been collecting and posting data on gender statistics in the art world for about a year. It started with an assignment for my students in which I asked them to tally the number of single-page ads in Artforum for solo exhibitions for male artists vs. female artists.

I continued to do this myself, each month, and would post the results on Facebook. Then I began to tally the numbers of male and female artists represented in LA galleries. It occurred to me that while everyone talks about inequity in the art world, I hadn’t actually seen data on it since the Guerilla Girls’ work in the 1980s.

I collected data on 50 galleries, and posted the results on Facebook. There was very fast and engaged response and the information went viral, not just in LA, but across the country.

I started inviting others to help me, and several artists contributed to a list of gender statistics for 100 local galleries. We then started tallying galleries in other cities as well (Santa Fe, New York, Philadelphia, Berlin).

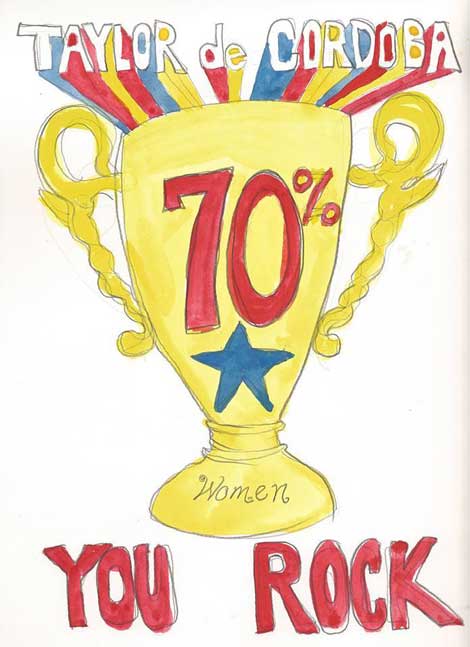

The poster component came when Kio Griffith asked me to be in his show, Margin Release Right, at West L.A. College on short notice. I didn’t have enough time to do a new project on my own, but the premise of the show—typing outside the margins, breaking through restrictions—made me realize that the data I had been collecting could provide a good foundation for a crowd-sourced project. I had the idea to make posters that visualized the statistics. Posters are democratic and public, and have a history that is rooted in mass culture and mass distribution. So I put out a call for artists to sign up to make posters that represented each of the galleries that had been tallied. Within three days I had 50 people sign up. Two weeks later, there were nearly 200 people on board. It was clear that this conversation really needed to happen!

I think it is important that this project is a collaborative project (and, yes, there are both men and women involved). We have formed a community of artists who are speaking out against an aspect of the art world that is undeniably and systemically unjust. The group has created and presented a creative and positive response to the very negative data—we’ve made art out of it. It’s also important to acknowledge that strategies of collectivity and collaboration have been fundamental to feminist history.

Reading the ArtInfo.com article about this project, I was struck by Guerrilla Girl Käthe Kollwitz’s comments on how much worse things were in the ’70s, with often 0% gallery representation for women. Do you agree with her that things have gotten much better?

I must admit that I was a bit dismayed to read this response. I think this is a misleading way to think about the numbers, because there were far fewer galleries then, too. If you tallied the overall number of artists who had representation in the ’70s, I bet the statistics would be similar to what they are now—which is about 71% male and 29% female. It has been over 40 years now and the rate of improvement is totally unacceptable. We might even say that things are worse. The “take what you can get” attitude, of being okay with less than what you deserve, concedes to the stereotypical expectations that a woman be gracious, self-deprecating, self-sacrificing, and grateful for the bones thrown to her by the capitalist patriarchs. No thanks! I do not accept.

What is the goal of the project, i.e., what do you want to achieve with it? I assume that it will travel and continue to evolve, be added to…

Ultimately, I would like to see this project encourage change in the art world that would result in a more balanced representation of male, female, and LGBTQ artists, as well as artists of color. I want there to be equal opportunity for women artists in galleries, biennials, magazine ads, articles, art fairs, private collections and museums. I want the prices for art by women artists to be comparable to those of male artists. I want there to be as many mentions about female artists in books as there are male artists.

The show will travel, yes. We are doing another version of it in the spring in LA, which will also include posters for New York galleries. Then I hope to have the posters on view in Santa Fe, New York, and as many other cities as we can get them to!

Micol Hebron works as an assistant professor in the Art Department at Chapman University, in Orange, CA, and is represented by Jancar Gallery in Los Angeles. She can be reached on Facebook, or through her website: micolhebron.com

For more poster images by participating artists, visit gallerytally.tumblr.com