From the light, airy and playful feelings of the Laguna Art Musem’s “Faux Real” exhibition on the main floor, the atmosphere of “Ex·pose: Beatriz da Costa” shifts into dark, moving and intense as one descends into the museum’s dark basement.

Da Costa’s “Dying for the Other” is a three-channel video installation dealing with the artist’s lifelong battle with cancer, with the show occurring not even 12 months after her passing—a timely and haunting exhibition of her last creation.

Beatriz da Costa made work that refused genre classification—seamlessly transitioning between contemporary art, science, engineering and politics—in many cases working in collaboration with forerunning art/technology groups such as Critical Art Ensemble, Free Range Grains, GenTerra, and Preemptive Media. Born in 1974 and raised in Germany, da Costa attended Carnegie Mellon University, eventually moving on to teach in the Studio Art, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Departments at UC, Irvine.

While watching da Costa’s video installation, it is hard not to hear echoes of self-mutilating artist Bob Flanagan. This is by no means a masochistic performance piece, but underlying similarities can be seen. The act of creation, of continuing one’s practice in the face of grave illness or disease takes not only a special kind of artist, but also a dedicated human.

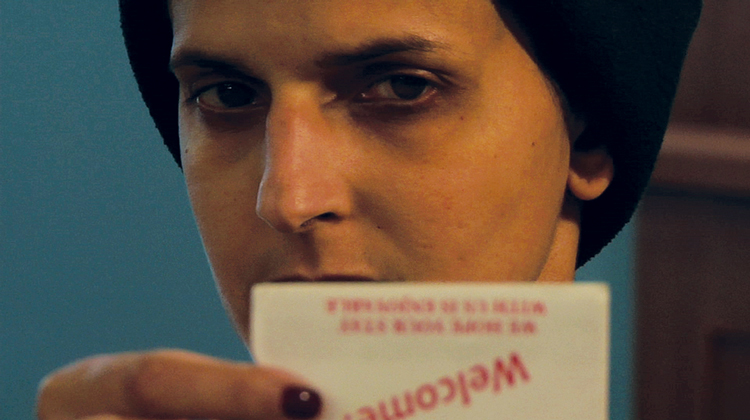

In Dying for the Other, video clips of mice that are being used in cancer research are projected and interspersed with video segments of the artist’s life as she is going through physical/cognitive therapy after having brain surgery to remove tumors that had spread from her breast to her brain.

Unfortunately, many of us have been touched by cancer. The battle with this disease is one of the darkest and most personal, in which the emotional toll is heaviest for those closest to the patient. In many cases the day-to-day heartbreak and immense medical traumas are hidden from the outside world, primarily internalized by the suffering person. Few want to be seen in public while fighting this battle, losing their hair, feeling constant nausea, fighting for their lives, all the while knowing that this may be an unwinnable fight.

This exhibition brings all of those hidden feelings and emotions quickly to the surface; but da Costa’s installation is not about internalizing the trauma caused by the disease. Rather, it uses that trauma as the catalyst to move forward, to affect some sort of change in the world. While the disease eventually ended the artist’s life, she refused to let it end her practice.

The videos of the artist in physical therapy coupled with videos of the cancer research mice—“test subjects”—begins to make a very dark link between the animals we use as proxy for our suffering and how little we really know about certain diseases. In many cases, there is no cure—only remission.

In one of the most striking moments of the installation, two of the three videos of the triptych fade away as a cancer research mouse is being pinned down and dissected, forcing the viewer to make a choice—to witness and participate in this experience, or to leave or look away. Slowly, a second video fades back into view—a close-up of the artist’s face staring directly at the viewer, engaging the viewer. It is mildly traumatizing and amazingly emotive. This juxtaposition between the dissection of this animal—so rough, so detached—coupled with this fragile human—emotionally dissected—staring back at you, it is intense.

Paired alongside “Dying for the Other” is da Costa’s Anti-Cancer Survival Kit, an approachable and informational coping device. Binding together the work of many artists and scholars, this collection is meant for those living with cancer and for their loved ones. The Anti-Cancer Survival Kit includes a database of comprehensive research, a coffee table-style book providing guidelines for anti-cancer approaches, interactive smartphone games or activities, and instructions on creating a therapeutic anti-cancer garden.

The pieces at LAM are staggering works of art that help to epitomize, and do justice, to what is important in life—and was, in her life. While locked into an epic battle for her survival, the most important thing to da Costa was her art. She needed to document this battle through her practice—to keep something for herself, something that the cancer could not steal. This is how the artist continued through the suffering—with grace, honesty, and continued art-making. I have the utmost respect for someone like da Costa—brave enough, strong enough and inspired enough to allow us to view the most intimate of battles, in a beautiful, memorable and artistic way.

Few exhibitions have the strength to resonate in one’s mind—reaching the viewer on an intimate level—for days or even weeks after seeing the work. Since experiencing this installation, there hasn’t been a day where it did not invade my thoughts.

“ex•pose: beatriz da costa,” ends September 29. At Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA, www.lagunaartmuseum.org

Above stills from Beatriz da Costa’s “Dying for the Other” triptych video installation (2011–12)