Your cart is currently empty!

Siri Kaur

“This Kind of Face,” Siri Kaur’s exhibition at the Cohen Gallery, reveals both the artifice inherent in the medium of photography and its ability to capture truth, however elusive and subjective it might be.

Kaur’s photographic subjects are professional impersonators of figures like Marilyn Monroe, Saddam Hussein, Julie Christie and Jack Nicholson. Her interest in these human simulacra extends beyond the at-a-glance kismet of their celebrity resemblance or the fantasy driven photo-op tourist attraction. By recontextualizing them within domestic spaces, parking lots and home goods stores away from the faux glamour of Hollywood Boulevard, she destabilizes our understanding of the celebrity and the copy. We are actually able to momentarily escape the tyranny of the simulacrum because Kaur lets us see beyond the representation. Wonder Woman poses in a living room, while Saddam Hussein sits in a garden, appearing not so much a brutal tyrant as a genial grandfather. Tina Turner and Elvis Presley swap stories in a dressing room. This disparity between the person portrayed and the environment in which they are photographed is often humorous; an amusingly anachronistic Abraham Lincoln stands stoically in a suburban field, tract homes visible in the distance.

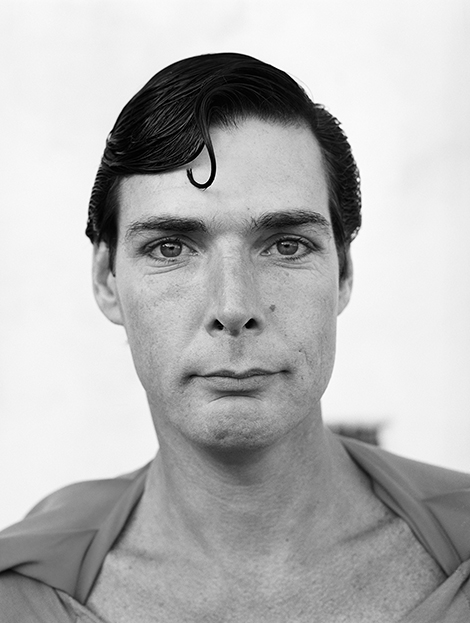

Sometimes Kaur dispenses with the scenery and focuses on the faces themselves. Perhaps the most affecting is a black and white closeup of a Christopher Reeves impersonator whose deep eyes, lined face, and tense, thin smile evince world-weariness. He is the epitome of the Roland Barthes’ punctum, that element of a photograph that captures our gaze and remains with us even after the viewing of the image is over; here, Kaur’s subject’s face wounds us with the knowledge that he is primarily valued by the world because he looks like someone else.

Complex layers of identity interact in Kaur’s work: on the one hand, as the impersonators are still in the guise of celebrity, we “recognize” them. On the other hand, we are not actually recognizing them, as we are looking at doppelgangers of familiar cultural icons. These are regular people, and the manner in which Kaur photographs them reinforces that. Her vacillation between humor and pathos highlights these complexities of identity, for the impersonators, quite naturally, do not appear to have the same responses to their jobs: for every vulnerable Marilyn and somber Christopher Reeve, there are the Jack Nicholson and Elizabeth Taylor impersonators, whose easy smiles and brimming confidence indicate their pleasure at making a living dressing up as someone else.

And that, in fact, is what Kaur seems to be after. She asks us to sort through our feelings about these people, moving us from skepticism and pity about why they would want to pretend to be someone else to a grudging understanding that a photograph is limited in its conveyance of truth, and that wearing a mask can be not only liberating, but is something that our fractured and absurd postmodern world often requires of all of us.

Comments

One response to “Siri Kaur”

Fantastic article. This photography is so engaging. I’ll definitely be checking out the show.