As part of a teaching proposal to the Autonomous University of Guadalajara in Mexico in July 1995, filmmaker Bruce Baillie makes clear what he believes to be the foundation for any kind useful communication, art, film or otherwise: “I want to present in my teaching, whatever the theme and/or external format, an essential question of Who Am I?” He believes this to be indeed essential, suggesting that without that first understanding ourselves, “we continue to live disparate, isolated lives, inventing empty and useless images which tend merely to misdirect our best efforts as a people who share a common Eden.”

Recently, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC presented Baillie’s films as part of an online shorts program in celebration of his life and artistry after his passing in April. This essential question of “Who Am I?” and in turn, “Who Are We?” guides us through Bailie’s work, and in his investigation, his films conjure feelings of compassion and humanism – what can easily be supposed as this “common Eden.” Through abstraction in composition and lyrical movement of the camera, Baillie guides us in his films with care to understand both people and landscape as part of a larger and networked society. Writing in reflection of Baillie’s 1966 short film Castro Street, Lucy Fischer suggests that Baillie “creates for the spectator an experience which transcends the nature of its literal subject.” Baillie’s films, largely functioning without explicit narrative or traditional plot, are committed to understanding our world and each other.

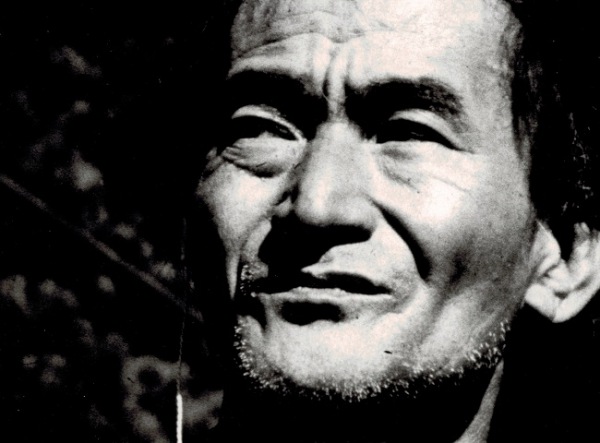

Still from Castro Street (1966, 10 minutes)

Castro Street is a ten-minute non-narrative documentary capturing footage of a street in Richmond, part of California’s San Francisco Bay Area. From whirs, mechanics and beeps of robust and engineered architecture, to orchestral swings and bending technicolor hallucination, it becomes more clear over the course of its ten minutes that this space is, above all, occupied by and for humans. These machines do not exist on their own – they are occupied by people performing labor for free movement. Though Castro Street operates without explicit narrative, it follows a trajectory of its own – documenting the street from top to bottom (oil refinery to lumberyard; black and white to color) he underscores points of difference and dynamism on the city street. To understand the working dichotomies here is to understand how we function in cities and do so together. Castro Street demonstrates a sensibility very close to Baillie – one of deconstructing and understanding formal opposites through abstraction.

In later films, his occupation with dynamic opposition takes form around the understanding of the hero and the outsider. To Parsifal (1963) is inspired by composer Richard Wagner’s opera of the same name. Like the original work, the film exists in three acts and serves as an abstract representation of character (and hero) Parsifal’s quest for the Holy Grail. Its lyrical structure in three acts presents a voyage out to sea – it’s unclear explicitly who is represented here as Parsifal and whether or not the quest is successful, but in the context of his wider oeuvre, we can assume that the Holy Grail is nature and fertile grounds. Baillie is known as a poetic lyricist, operating in the 1960s through complex and condensed cinema. Contemporary filmmakers Michael Snow, Paul Sharits, and Hollis Frampton as ‘structuralists’ simplified filmmaking to understand the essence of its operation – but for Baillie, its content served as the essence for what he believed cinema, as a communicator, to be: a tool for understanding the self and the world.

To Parsifal is the first in a series of three films which also focus on an understanding of the world through ideas of heroism – Mass For the Dakota Sioux (1964) and Quixote (1965) comprising the next. Baillie’s Mass does not explicitly show members of the Native American Sioux tribe, but instead works as a requiem for the native people as “a celebration of what has passed away from our hysterical milieu of materialism.” Similar in form to what would later comprise Castro Street, the camera works to superimpose industry and nature; condemnation and innocence. As he followed operatic form in To Parsifal, here he follows the structure of a Catholic Mass to demonstrate the Native American’s religion-of-sorts, a commitment to nature and sustainability through time. The sombre tone of sound and music reverberates through the piece as if an accompaniment to an emblem of remembrance. Shots of the American flag behind a wired fence, juxtaposed with a heap of disused and abandoned cars piled atop one another demonstrate excess and entrapment.

Still from To Parsifal (1963, 16 minutes)

The superimpositions emphasize this contrast of beauty of nature and the pitfalls of American capitalism. This is not to say he is dismissive of the evolution of technology – in fact, he seems to readily embrace the image of the train as a positive metaphor for progress. His commitment lies with understanding the dynamism between hero and misfit and their related power structures – key influences for later filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. The echoes of the question “Who Am I?” reverberate.

Quixote (1965) is perhaps the most exemplary of all of his works – it weaves together the themes and structures from his earlier films. The story of Quixote, of course, is a parodic tale of a foolish hero who wanted to be a knight and goes on a long journey to become one – here, we find in abstraction an extended reflection of heroism, war, and political action across an American landscape of beauty and advancement. Groaning sounds of industry match the abstraction of the environment – blurred shots of rural American landscape to banks, high school basketball courts and playgrounds. The sound seems to rupture over fleets of military planes, with crackled radio transmissions ominously accompanying the procession of army tanks. Quixote works as an existential examination of what it means to be American, in quixotic terms. Progress does not exist here as a throughline, in alternating from rural landscape and farmland to industrialized and militarized spaces, they exist symbiotically. Political protest – here with footage from Selma – is demonstrated as the in-between space – a space for anguish, but also for deep humanity. For Baillie, industry is not a symbol of advancement per se – there’s an argument for the great and bountiful nature of the natural environment and our power in coming together to make change. To understand each other and to improve our world, we must understand ourselves.

There’s very much a sense of mysticism around Bruce Baillie’s films – his works are distinct character portraits of landscape and offer a human view on our world. In 1997, Amy Taubin called his one-shot, three-minute film All My Life possibly “the only perfect film ever made.” The experimental lyricism of his films, and the deftly constructed cadence they offer through fusion of sound and image, create a characterization of the natural environment whereby nature feels emotive. Named the “unofficial anchorman of the West Coast underground,” Baillie founded Canyon Cinema in 1961 and worked actively to promote artists and filmmakers who used the technology of cinema for experimentation and compassion. For Baillie, filmmaking was deeply political and a tool to understand humanity. To ask “Who Am I?” is the first step to seeing and knowing the world.