“Get off Bonnie Brae!” Chris Kraus shouts from the car speakerphone when I resort to calling her for directions. I’m lost in MacArthur Park, a neighborhood that borders downtown Los Angeles, looking for the writer/critic’s house. I wasn’t sure if Kraus raised her voice for my safety (Bonnie Brae is a notorious drug-copping street), or just to point me quickly in the right direction. When I finally make it to her house, the garage door magically opens—how thoughtful, she must have been watching for me.

I climb the stairs to what appears to be a complex of two separate California bungalows, one close to the street and the other further back. In between there’s an inviting patio area with a table and chairs; I imagine Kraus hosting evening BBQs with her intellectual crowd. Kraus enthusiastically greets me from the house in the back. Blaze, her scruffy wirehair terrier mix, welcomes me as well with her non-threatening bark. Kraus and I have met casually only a few times and once again her friendly demeanor impresses me.

Dressed in a matching tan sweater and cardigan with black slacks, Kraus, 62, wears no makeup. Her mussed-up brown mane shrouds her delicate-featured face, and her blue eyes sparkle as she invites me to set my things down in the first room down the hallway, an extra room that could be an office—although she told me that the other house on the property was actually her office. The room is spare, with built-in bookshelves, a small black leather couch and a coffee table shoved to the side. The wood paneling is dark, matching the wooden floors with only the hazy mid-afternoon light coming through the windows on a rare overcast day. Two paintings hang on the walls, though barely noticeable as the colors are neutral and dark. Kraus heads toward the kitchen to make us some tea; I follow (uninvited), craning to see other parts of the house, looking for what art she might have on her walls. As she puts the kettle on the stove, I remark on a Sue Coe drawing in the kitchen. She tells me there are some great paintings in her office (the other house) if I want to go and check them out. A Henry Taylor is going to be framed soon, she excitedly informs me; it has been rolled up for years underneath some furniture.

Chris Kraus in front of her MacArthur Park bungalow, photo by Reynaldo Rivera.

As I sit waiting in the room for our tea, I wonder if we will be sitting on the loveseat together, as there are no other chairs. It might be awkward; I would have to sit sideways facing her the whole time. Kraus then arrives with two large cups of tea, hands me mine then immediately falls into the couch right next to me. She flips off her shoes, settles in, and scrunches her knees up to her chin. The tea tastes good and I don’t have to wonder anymore.

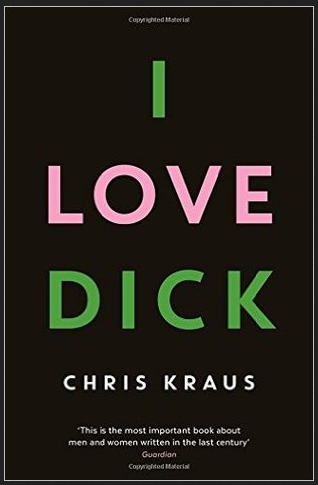

We’re here to talk about I Love Dick, both the book and the screen adaptation for the upcoming Amazon TV series of the same title (why fuck with a good thing?); we agree that we might discuss the art world later. The pilot, the first episode of the series, has been available since last August. Director Jill Soloway, who has had her share of notoriety with her widely acclaimed, also-Amazon production, Transparent, is at it again with Kraus’ book. Soloway, also executive producer along with Andrea Sperling and Sarah Gubbins, are all key players in the production. The full season is scheduled to come out early May.

I Love Dick is a feminist cult novel by Chris Kraus, part memoir/part fiction, which traces her unrequited love for Dick, a colleague of her French theorist husband, through the form of the letters she writes to Dick. Mixed in we find art criticism, road trips to and from New York and LA, a troubled marriage, a longing for love, and mostly a longing to be heard. It was published 20 years ago, a lengthy gestation, even for Hollywood.

When asked how she feels about her book being made into a TV series, a wide grin appears above the teacup she is clutching with both hands. Even before Soloway and Sperling came and approached Kraus about a TV show, the book had been steadily gaining popularity over the years. It didn’t exactly happen overnight Kraus tells me in her fading New Zealand accent. “It wasn’t like zero to sixty; it was incremental.”

The book was reissued a decade later, in 2006, and timing-wise, it couldn’t have been better. The reprint made its way onto the web. “The blogs traveled a lot faster than a zine in the ’90s,” Kraus points out. Female bloggers such as Kate Zambreno and Jackie Wang were writing about it. “It started popping up all over the place,” Kraus says, jokingly adding that it was written up in a British Airways magazine only two years ago. “Even Lena Dunham tweeted it. It definitely had made all these incursions into the larger world as a young woman’s book.”

NEW YORK

Books were part of Kraus’ background from the beginning. Her parents owned and operated an independent press called Brick Row. Kraus spent her childhood in New Zealand and attended Victoria University of Wellington. She studied English, “like anybody else,” she says offhandedly. “Certainly my parents had hoped and expected that I would be a writer.”

After college, Kraus worked for a daily newspaper for a few years. “All I knew at 21 is that I didn’t want to still be a journalist when I was 41 living in New Zealand,” she recalls with some relief. So off she went to New York in the mid-’70s, hoping to be an actress. She studied theater with members of the Wooster Group, among others, but it became clear that acting wasn’t her game. She was encouraged to direct, which led to Kraus becoming a filmmaker. She showed her work on the underground and independent circuit: “art films—the kind of films that would now go straight to a gallery,” she says. She mainly made shorts, and one feature-length movie, Gravity & Grace—her most commercially inspired film—but it was “a disaster,” she plainly states.

Kraus mostly hung out with poets, around the St. Mark’s poetry project—more a literary than an art crowd, although artists were around. She told the story of how she would reluctantly feel obliged to visit artists’ studios back when she lived in the East Village, “I felt—like a lot of people—put on the spot, when asked to look at visual art.”

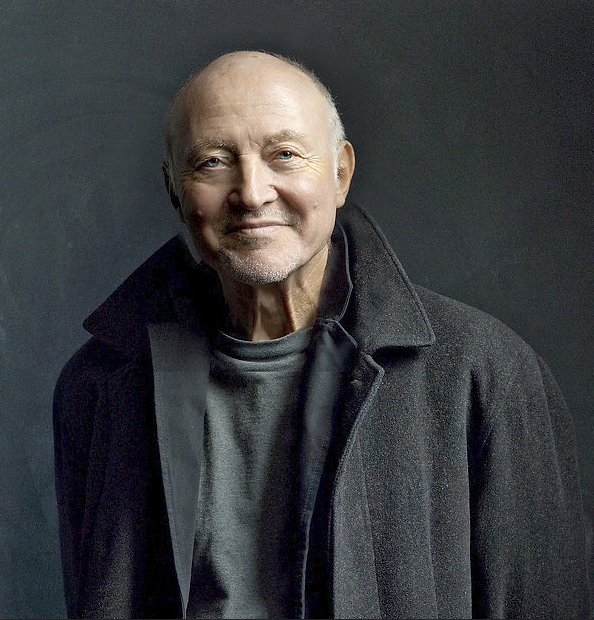

Sylvère Lotringer

In 1980, Kraus crossed paths with French theorist Sylvère Lotringer, her soon-to-be husband, but it wasn’t until three years later that they became a couple. Lotringer had founded Semiotext(e), a cultural studies journal, in New York in the early ’70s, that still thrives as an edgy press today. Kraus and Lotringer must have been quite an item back then—arty young filmmaker with celebrated cultural theorist. She fell in with the Semiotext(e) crowd, creating and launching a press imprint called Native Agents in 1990, publishing mostly women’s fiction. Lotringer’s friends included some of the world’s leading intellectuals—French theorists like Jean Baudrillard and Félix Guattari—all of them decades older than Kraus. She must have been the center of attention and admiration, with her talent and youthful good looks.

Kraus and Lotringer stayed married for more than 20 years. They lived together in New York in the ’80s and ’90s, but parted ways in 1995 when Kraus moved to LA, alone, to teach at Art Center. Many of Kraus’ books include Lotringer as a major character in her life/story. I Love Dick can easily be seen as a love letter to Lotringer, her gentle way of saying it’s over, that she needs to spread her intellectual feminist wings; their marriage was never going to be a conventional one. Kraus said of Lotringer and her East Village friends, “I was equally influenced by both worlds.” The intellectual mixed with the sensitive; the high and low art. This becomes an exploratory theme in both the book and the TV series.

That fateful dinner that started it all: Bacon as Dick, Griffin Dunn as Lotringer, Hahn as Kraus.

OTHER STUFF

We now know I Love Dick is not about someone loving cock (entirely) but actually about an “aging ingénue” (Kraus’ words) who falls in love and becomes obsessed with Dick Hebdige—author of Subculture: the Meaning of Style—a colleague of her husband. After only one night of flirting, Kraus creates this world where she becomes obsessed with rejection and dejection, emotions that drive her to write and write and write, but only letters to Dick—the one force that transforms her into a writer.

“For me, when I wrote the book, what opened the door was to suddenly have an addressee. I’d never been able to write before, and I always got hung up on tripping over the “I”—terribly self-conscious and not able to sustain it. But the beauty of writing a letter is you’re talking to somebody. So, for me, the key thing was the loop, I mean it was a one-way loop, because he [Dick] didn’t write back, but, I had somebody to talk to.”

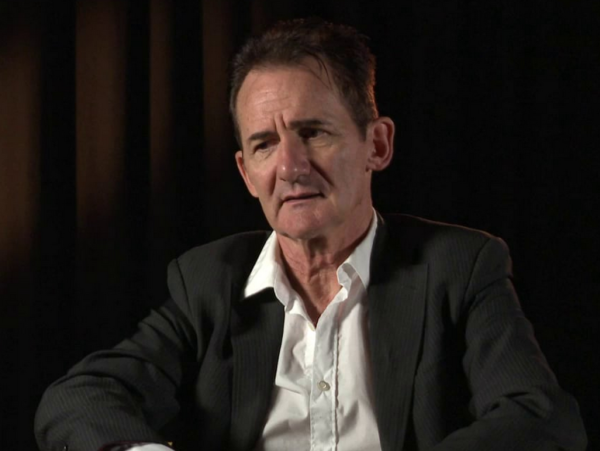

Dick Hebdige

As Kraus writes the letters, she also realizes they are shaping into a book—readers witness her excitement and her discovery that she is becoming a novelist. The copious letters all to Dick, all unanswered, are candid, raw confessions of abjection and unabashed sexual longing. I Love Dick is an exposition of Kraus’ real life that actually happens when she’s writing the book, if we are to believe what we read. She crosses more than a few lines with her use of real-life characters that are a part of her life, or so we think. Dick, we learn is Dick Hebdige, the object of her desire—her muse, the McGuffin? And Sylvère Lotringer is her real-life husband. Throughout the book are references to real artists, real movies, real places. Even in our interview, several times Kraus responds, “just like it is in the book,” as if I might have every page memorized.

But there are a few things that are not just like in the book. On the first page, for instance, Kraus states she’s not an intellectual; she admits to me that line was disingenuous. “It’s being light and coy. The character Chris is living with a well-respected and prominent intellectual. She is often in the company of other intellectuals who are his friends. She’s playing the role of the wife, of the intellectual’s wife. She’d be coming from a very different place than if the Chris character were not married to Sylvère’s. If she was just a single woman, it might be a little odd for her to take great pains to call herself not an intellectual. But in the context of being the wife of a philosopher, it’s funny.” Actually quite often it is the case in real life. Think of the effervescent faculty wife. “[It was] my character mask,” she goes on to explain. “If you think of your persona ending up as a character mask, mine was the aging ingénue. So everything that I think and feel and say, is coming through that mask as the ingénue.”

Kevin Bacon as Dick, in the TV series.

Reading the novel, I felt a connection, an appreciation for her aching honesty, her humor, her sisterhood for writing about female artists she has admired and wanted to draw attention to. She’s interested in Hannah Wilke, whose work is discussed at length in a letter to Dick. Her mixture of art, raunch and keen perception reawakens the senses like a new kind of drug.

I Love Dick is lauded as a cult feminist book, but did Kraus intend that? “No!” she cries out. Kraus is of course a feminist, but her book did not have a feminist agenda. Even without that intent, she “was very interested in the way women had been marginalized in the art world from the late middle century.” The book didn’t exactly reek of feminism for me either, but Kraus’ brand of feminism creeps up on you. It doesn’t slap you in the face. Instead it hits you in the gut, in slow motion, with soft pillowy punches. Certainly Kraus doesn’t object to her book being labeled as a feminist work; she even marvels a bit, but she persists, “Even the question of the female gaze, I wasn’t really thinking that. I was thinking about other stuff.”

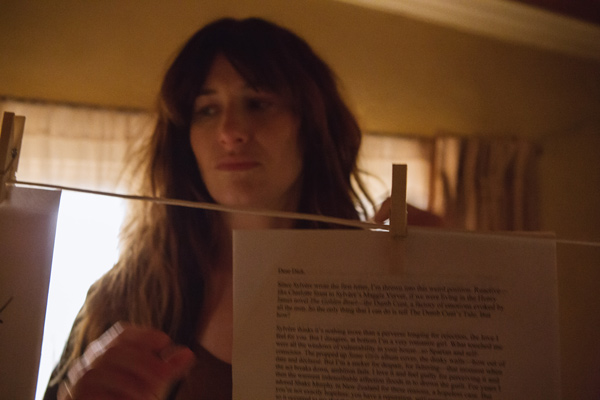

Kathryn Hahn as Chris Kraus in I Love Dick, the TV series

What other stuff was Kraus thinking about? The TV series seems to key in on that very concern. The viewers are also very interested in what Kraus is thinking about. And Soloway is thinking about the female gaze, as she said in an interview at Sundance where it was screened last year. Although the script appears to not follow the book too much, it seems to capture Kraus, which is really what I Love Dick is all about—Chris Kraus.

The TV version is set in Marfa, Texas, as opposed to LA and New York, the main locations in the book. But these differences do not concern Kraus. She is very onboard with the adaptation. “It’s a TV show, it has nothing to do with me,” she responds when I suggest anything otherwise. “It’s existentially very similar, every transposition that they did and change that they made was absolutely right.” Kraus has nothing but deep admiration for all the actors: Kevin Bacon as Dick (Dick Hebdige, who remains elusive in the book, is much more present in the series). Griffin Dunn is “an amazing choice to play Sylvère,” Kraus says, “He’s a wonderful actor, but so much more than an actor as well.” And Kathryn Hahn (who also has a role in Transparent) as Chris: “Ohhh… does it get any better than being played by Kathryn Hahn?” Kraus coos. Indeed, it feels perfectly cast. Hahn and Kraus have a similar look—thick light brown hair, almond-shaped blue eyes, high cheek bones. “And she’s a brilliant actor,” Kraus adds. “In that first episode, she so brilliantly captures that sort of existential dilemma of not knowing where to put yourself, every move you make is wrong, you’re constantly walking through a minefield. And she’s gonna dig her way out of it somehow.”

Kathryn Hahn as Chris Kraus in I Love Dick, the TV series working with her letters to Dick.

In the book and the series, Chris is a filmmaker. But the series parts from the book when Chris accompanies Sylvère to Marfa for a residency where he will study with Dick. She’s just along for the road trip and plans to make a detour to the Venice Film Festival for the debut of her feature-length movie, Gravity & Grace. I asked Kraus if she would have preferred being behind the camera for the TV production, since after all, she started out as a filmmaker and it’s her story. But without any hesitation, she declares, “Oh, not at all! No. As soon as I started writing the book, I was finished with filmmaking, forever. It’s a sweet irony, but it’s ended up being this really mainstream TV show, [which] I would have died for back when I was making films.”

Thus began Kraus’ career as critic and writer. She’s written six books in all since I Love Dick. Another is due for release in August by Semiotext(e): a biography of Kathy Acker, who was also published by Semiotext(e). Kraus is still a co-editor with the publishing house, and Sylvère lives just around the corner from her in Los Angeles. Who would have known that when Chris Kraus was outside that New York gallery in the ’90s, smoking a joint, getting ready to look at some art and write about it, that she’d one day become a writer, and that her parents could then be proud that their daughter did one day become a writer. Maybe they do cringe a little when they have to tell friends their daughter’s first book is titled I Love Dick, but now it’s on TV too!

All film stills courtesy Amazon Prime Video.