I met David Horvitz three years ago when he hand-delivered me an edamame plant he had been offering to his community via social media. Now, three years later, we meet again to conduct this interview in the garden he has been building. The garden in question is a previously vacant lot in Arlington Heights, a neighborhood in Central Los Angeles, near the Underground Museum and his studio. The lot, which became vacant after the house on the property burned down, is roughly 5,000 square feet and, prior to Horvitz’ interventions, was mostly dirt, grass and weeds. “I’m always finding buried knicknacks from the house when we dig. A lot of marbles,” Horvitz tells me.

Horvitz has worked with horticulture in several instances, though this is certainly his largest-scale and most ambitious plant-based work to date. The artist, age 39, who now lives and works in his native Los Angeles (after a stint in New York on graduating from Bard’s MFA program in 2010), first exhibited horticultural work when he planted seeds in a book that eventually grew into a tree. The seeds used were collected from Zuccotti Park during the Occupy Wall Street protests there. When making this work, Horvitz was “thinking about the trees as shelter and also as witness to this political moment that was happening in the background of the landscaping.” The tree was donated to, and currently resides at, Bard College, where it was planted in the ground and has since grown quite large. This notion of trees in the foreground, with bodies as subplot, persists throughout his oeuvre, culminating in his most recent work, his garden.

Early stages of David Horvitz’ garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol.

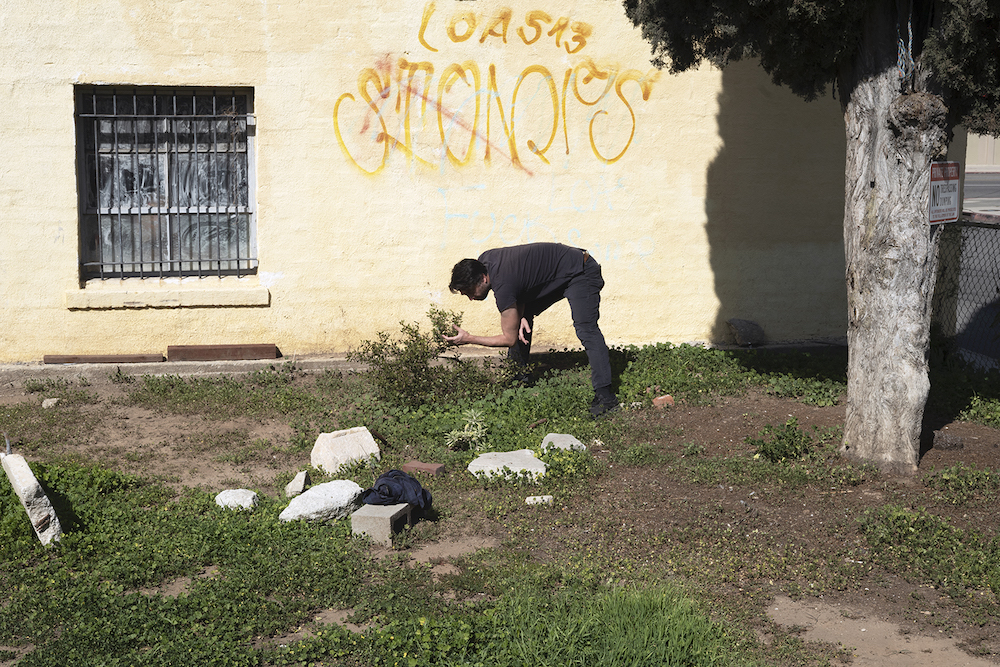

When I arrive, the garden, which is still awaiting its concrete benches, is awash with midday sun. The space is entirely exposed, as much to the elements as to the street. The street, despite its proximity to bustling Washington Boulevard, is residential and fairly quiet. We walk through the garden while Horvitz gestures and tells me each tree or new bloom’s horticultural story—where they’re native to, where the seeds are from, and how they grow. He spots a new bloom—a tiny green leaf sprouting from the soil almost invisible to the untrained eye—and is visibly excited, placing a rock next to it to ensure “we (I know that in reality he means me but is too polite to say so) do not trample it.”

After obtaining permission from the lot’s landlord, Horvitz teamed up with architectural design firm TERREMOTO to transform the derelict space into a garden. When planting they talked about holding a designated space reserved for people but decided, instead, to allow the trees to dominate. In urban gardens, trees typically exist in the background, activated by the bodies that visit—thinking of his earlier project, they wanted to consider how it might feel for bodies to take a backseat while the trees hold centerstage. So far, they have planted over 100 trees. The garden’s concept required rocks so Horvitz and David Godshall, of TERREMOTO, reached out to LACMA Curator Christine Y. Kim to gather rubble from the museum’s demolition site. The result is a zen rock garden, a transplant of urban ruins from a renowned longstanding art space repurposed to another (much more transient) art space. If LACMA’s controversial and politicized demolition has been critiqued as a symbol of waste and excess, then Horvitz’ garden is the antithesis; a space lacking in financial incentive built up from the ruins of a domestic building and incorporating ruins from an institutional one.

Freshly cultivated garden by David Horvitz and David Godshall. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol.

The Davids (Horvitz and Godshall) are unclear exactly how the location will be used. They may open it up to arts programming such as related talks, performance and happenings. Though it may just be a garden, open by appointment. He mentions its visibility to the public and that some neighbors have expressed wanting to have a BBQ or party there. While wanting the space to feel communal, there is simultaneously a need to preserve. The main rule is that it is a place for the plants, where the people are merely visitors. This tension of public vs. private continues to make itself known; the garden is visible from the street but behind a gate under lock and key. There have been several instances of graffiti which Horvitz is undecided on how to address. “I’m tempted to keep it,” he says. “Or incorporate it into a mural.”

Horvitz has long been considering the boundary between public and private. Since graduating from Bard in 2010, he has become quite known for his mail art and virtual artwork, drawing on the influence of conceptual artists before him like Bas Jan Ader and On Kawara. His early film “Rarely Seen Bas Jan Ader Film” (2009) was uploaded to YouTube under the premise that it was “found in Ader’s locker at UC Irvine after his disappearance at sea in 1975, and that the film was assumed unusable because it abruptly runs out just as the figure enters the water.” The few-second-long black-and-white film depicting a figure biking into the ocean was then made into an artist edition book, published by 2nd Cannon Publications. This blurring of fact and fiction, or history and mythology, discreetly inserts itself into the narrative—thus questioning the bounds of privacy by pushing them. I was first introduced to his practice with his 2007 work, I will think about you for one minute, where one can pay $1 and Horvitz will think about them for one minute, emailing them the time he starts thinking, and the time he stops. With this piece (still ongoing) he challenges the intimacy and visibility between artist and audience, momentarily collapsing the distance between the two. Particularly notable is the second email he sends once the minute is up: “I’ve stopped thinking about you.” Here, Horvitz draws a stark line between the public and private.

Horvitz tending to the garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol.

Central to Horvitz’ work is the notion of access. Alongside many gallery and institutional exhibitions, including a group exhibition at the ICA Los Angeles this Spring, a solo at Nassauischer Kunstverein Wiesbaden in Germany earlier this year and exhibitions at Praz-Delavallade and Yvon Lambert in 2020, Horvitz extends his practice to inexpensive printed matter and free downloadable materials. His books are translated into 32 languages (so far), and his web content is downloadable via PDF, audio file or transcript from the website itself. He refutes the gate keeping oft associated with the arts and refers to his collectors less as “buying” his work, instead favoring the word funding. In one body of work, “Donations to Libraries” (2010), Horvitz donated archival boxes—one of which went to MoMA New York. The boxes, which appear as first-edition hardbound books but in reality contain a bottle of gin and a glass, were purchased by collectors who, in the acquisition contract, agree to buy a new bottle for the bookcases (which still live at the respective libraries) each year.

Horvitz addressed the public property conversation head-on in his two bodies of work: “Public Access” (2010–11) where he photographed himself on various California beaches and uploaded those images to the beach’s Wikipedia pages, and “Private Access,” where he did the same thing but on east coast beaches which are adversely privately owned. Exerting his public right both physically and digitally (in the case of the publicly gathered encyclopedia, Wikipedia) Horvitz explored the bounds between private and public access and the feeling of existence and visibility in both spaces. In a similarly terse video work made around the same time, A Walk at Dusk (2018), Horvitz walked through Trump’s Golf Club on the coast in Palos Verdes planting seeds from the Washingtonia robusta, a native Mexican fan palm. A gestural action in the face of the Trump presidency and his intended “wall,” Horvitz reclaims the land (which must, by California law, provide beach access to all 24/7) with native Mexican horticulture, collected from his grandmother’s garden.

Portrait of David Horvitz in his garden. Image courtesy of artist. Photographer Olivia Fougeirol.

Horvitz, who has been working with galleries and institutions for the past two decades, has made a habit of pushing boundaries. For a Frieze New York Project in 2016, curated by Cecilia Alemani, he hired three professional pickpockets to attend the fair and stealthily distribute artworks to randomly selected fairgoers. At last year’s Frieze Los Angeles in Ruinart’s Champagne Room, he organized to gift glass artworks. The caveat being that in order to receive one you had to repeat the daily rotating password, which was shared without context by a mysterious gentlemen whose main role was to walk around the fair whispering the elected password into the ears of the public. Horvitz maintains that he does not eschew the traditional buy/sell market dynamic, rather he prefers to “make it a bit more difficult.”

Horvitz’ garden, as yet untitled, includes an artwork (or group exhibition, as he sometimes refers to it) which is collaborative in nature. Dirt Pile (2021-ongoing) is a cumulative pile of soil, so far featuring contributions from international artists. Morphing his own work with the contributions of other artists, Horvitz shirks direct ownership and invites other artists to inhabit his garden, via the soil from their homes. The garden—to which the landlord could at any moment extinguish David’s rights—is a practice in cultivating the ephemeral. Throughout this project, and over the course of his practice, Horvitz explores the balance between private and public, relishing the tensions between the two. Participating in both public and private spheres, Horvitz straddles both sides and revels in their inextricability.