While earlier exhibitions used horse racing as a point of departure and a metaphor, perhaps, for the handicapping aspect of the art world, “FROM HERE,” recently on view at Jenkins Johnson Gallery in San Francisco, focuses on artist Sadie Barnette’s impressions of her urban home environments. Oakland, where she was born, and her mother Ellen still resides, and Compton, where she spent time with her dad Rodney’s extended family, are used as a counterpoint to both the worlds of fairytale sparkle and the Black Panthers.

An installation of photographs and works on paper occupies a long wall of the large front gallery; sprinkled throughout are sparkling pushpins, spots of glitter, or bows. Large sheets of paper are tacked to the wall, some bearing images of cars or people. In Untitled (Babies) (2016), a small photo of children, folding chairs and toys—a party on a concrete backyard patio in West Oakland—floats above neon spots of hot-pink, electric-yellow and black spray paint. Negative space abounds throughout. Adjacent, a grouping of vintage and current Family Photos (dates variable) wraps around an interior corner of the gallery, one of a young Rodney cradling his baby daughter to his chest is particularly moving.

Sadie Barnette, Untitled (Pills), 2016; ©Sadie Barnette, courtesy of Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco.

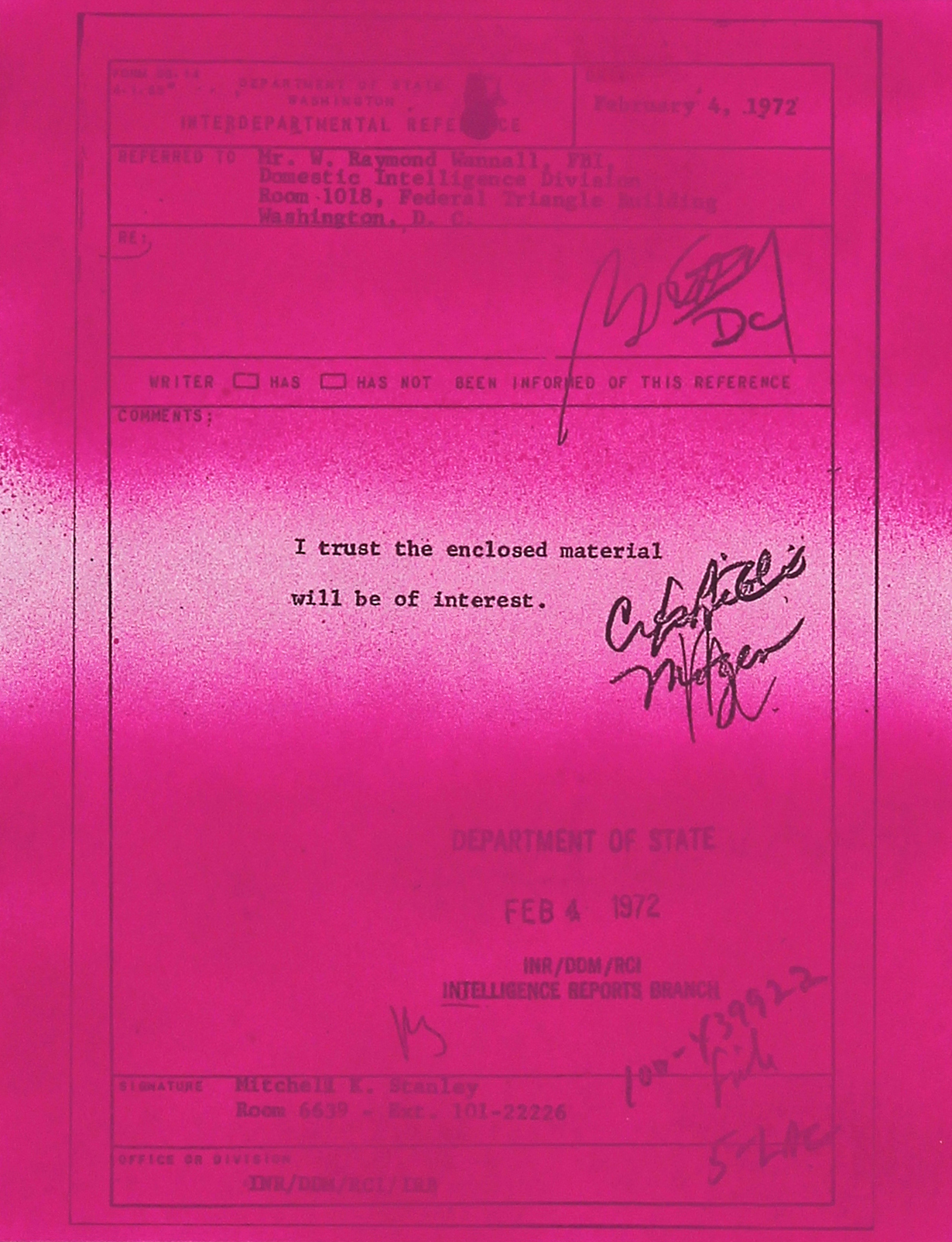

A 500-page document compiled by the FBI on the actions of Rodney Barnette, one of the co-founders of the Black Panther’s Compton chapter, provides pages used in a series of works mounted on black Stonehenge paper. In Untitled (FBI Enclosed Material) (2016), the cover page of the document, spray painted with a hot-pink color, rests on the deckled black rectangle, itself surrounded by a thin white mat, in a thin white frame. Where the spray thins out, the words, “I trust the enclosed material will be of interest,” stand out. Barnette’s involvement with the Black Panthers placed him squarely on the FBI’s prime target list. On the opposite wall, a framed vintage letter from the artist’s dad to her cousin Sophie documents his activity in the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis—as well as referencing family parties in Compton. Here the personal and the political are inextricably intertwined.

A striking image of a section of chain-link fence, layered above a background of hot pink in varying degrees of saturation, epitomizes the contrast of the harsh with the alluring, a world where danger and the stark realities of city life intersect with the fantasy world of the imagination and potential for transcendence. A text-based piece, Untitled (Compland) (2016), conceptually conflating the two cites so central to the formation of her identity, hangs in a white frame on a gridded background repeating the chain-link fence imagery.

With all the layers of content vying for our attention, the overall effect of the work is surprisingly minimalist; Barnette’s analytical process—her system of marking, sorting and organizing the images and content—interjects thick layers of both physical and conceptual space between the viewer and the assorted imagery. Her ability to transform such loaded content into a hopeful, elegant and poetic statement is clearly sleight of hand.