Named after Pablo Neruda’s epic poem on the history of the Americas, Rodrigo Valenzuela’s own “General Song” harmonizes with its Lantinx perspective; his two series of photographs, “Barricades” and “Masks,” confront social issues like immigration and revolt while meditating on the medium of photography.

The primer-white and paint-chipped scenes of “Barricades” exist in simultaneous construction and dismantling, both in material and in concept. The foreground objects of “Barricades” build off, and extend into, a large photograph affixed to the wall, showing how they were arranged in a previous moment (captured in the photograph). “Barricades,” a series that ruminates on the artistic process and object perception, raises more nuanced questions about photography and complicates our relationship to it.

Even though the mechanics of a photograph (recording a single moment) make it resistant to showing the sequence of its own becoming, Valenzuela’s “Barricades” exhibit an artistic process we might expect of other, physical media, but still maintain the temporal precision characteristic of photography. The inner and foreground scenes, with their reused and rearranged objects, suggest a brief increment of time, yet their objects rest on each other as if no time separated them at all. “Barricades” are simultaneously breaking the moment in two and mending it back together.

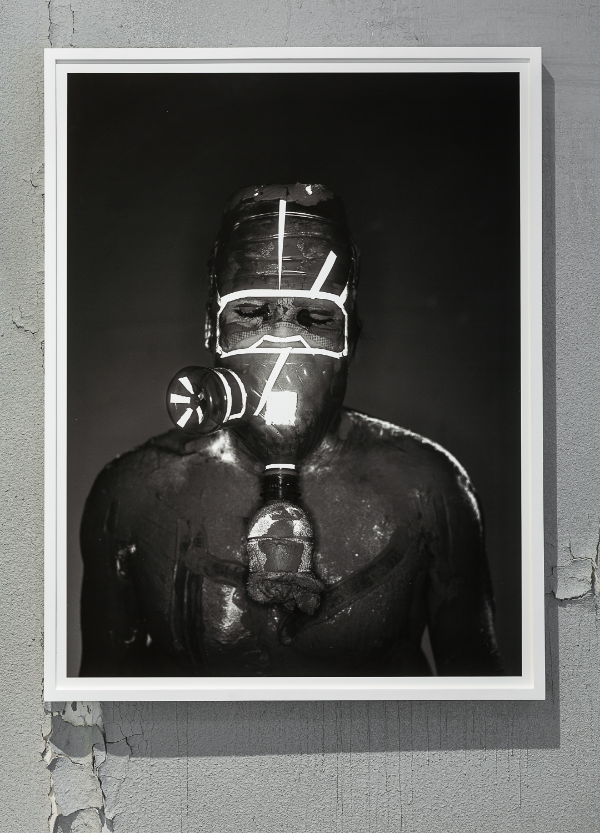

Rodrigo Valenzuela, Mask #3, courtesy of the Artist and Klowden Mann, Culver City, photo by Matthew Farrar.

Photography, too, maybe because it can preserve a moment otherwise lost to time, carries with it a certain sentimentality, or at least the blueprint for it. As a photograph is intended to store visual information as close as possible to our own visual experience, the more accurate the photograph, the more it invites the viewer to enter its space—to reclaim a past moment. “Barricades” sabotages that natural response. The series leads the eye, tricks the mind, and asks the viewer to step inward through the planes of the image, into the interval of time suspended between the foreground and inner photo (perhaps even into the solitary realm of the artist’s process). But at the same time, they obstruct. In the details in the periphery, Valenzuela deliberately reveals the illusion, almost forcing us to admit: we want to be deceived.

In both “Masks” and “Barricades,” Valenzuela employs art’s unique ability to connote multiple ideas and feelings without actually declaring what it is, or even being something at all. And he orchestrates those connotations in such a way that the interactions between them create the ineffable experiences that his audience, as art-makers and viewers alike, should seek out of art. With “Masks,” a series of tenebrous but electric portraits of mud-covered men wearing makeshift respirators, Valenzuela somehow achieves this with political and social issues, where voices are often so strident that they stifle the viewer’s ability and willingness to explore or experience different ideas—especially in today’s political climate. While others might equip politically-charged objects to incite, Valenzuela’s mastery of detail and ambiguity instead cultivates a sensitivity and awareness. In an air of riot and ritual, “Masks” enables the viewer to commune with the subjugated and the defiant, the hopeful, the indigenous, the dead.