Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Cooper Johnson

-

Lauren Quin ‘Clutches’

Real Pain Fine ArtsAt a time when abstract painting seems mired in self-reference, I itch for shows like “Clutches,” Lauren Quin’s second solo show in Los Angeles. Quin’s paintings are impressively complex. They feel like the orchestrated chaos of Albert Oehlen, but with an affinity for biological form and the slightest reference to digital image-making. Quin has a prowess for complicating images, enabling her to stir unusual reactions and offer insight on the painting process.

Oddly, Quin achieves so much with minimal means—her paintings rely heavily on a simple gradient motif. On its own, her version of this motif already has dual connotations of a light source and of form. But Quin often imbues it with a deeper biological connotation. The paintings sometimes feature larger forms, often flesh-toned and embryonic, and sketches that look like they’ve been scratched into the surface; ranging from animals and hands holding eggs, to patterns that look like feathers and scales. Quin’s interest in biology, and often her aesthetic, bring to mind Terry Winters’ sinuous/structural paintings from the eighties and nineties, but the effect is often more unsettling. There’s a certain black magic in tricking the mind to associate inert objects with biological liveliness, sort of like the quasi-limbs in Clutch for Dasypeltis. Thomas Nozkowski mastered a similar trick, although the two artists have very different aesthetics.

Gallery view courtesy of Real Pain Fine Arts Quin’s painting is more complicated than tributes to biological form, though, partially because she subtly references the computer’s influence on image-making. Quin uses the gradient motif as you’d see it in a computer program, as if copied and pasted or drawn by a cursor. Having so many discrete elements also feels very digital, at least to this reviewer. Though there are comparisons to Laura Owens or Albert Oehlen’s “computer paintings,” Quin doesn’t quote these digital aspects so literally, and her work doesn’t depend on this interpretation. Her paintings also don’t succumb to being mere “images” rather than paintings.

Quin’s work has a lot to do painting-specific issues, and she subverts some of the traditional notions of painting process. For example, many of the longer gradient elements mimic the speed and movement of a gesture, but are actually made by the much slower process of creating a gradient (Clutch for The Penitent, for example). And they also read as form in addition to “marks.” Many of these gradient elements are also positioned such that they look like they’re about to connect, and form something larger, but remain detached—suspended in a process of becoming. Their texture feels finished, but their edges feel incomplete. And by using the gradient motif repeatedly, so much of her compositions (whether forms, movement, gestural patterns) are atomized into a litany of first steps, each its own slow process.

Lauren Quin, “Clutch for an Open Palm,” (2020). 32″ x 52,” oil on canvas. Courtesy of Real Pain Fine Arts. I love this about Quin’s work because certain things about painting have become overly romanticized: the splash of paint, the mark as a record of the moment, the entire idea of a painting being a record of its own creation. Arguably, this human element is what makes a painting a painting, but at the current moment, it mostly feels stale and narcissistic. Quin finds a way to make it new. And in our changing world, Quin’s vision of biologically-imbibed and digitally-conscious abstraction gives hope for what painting can offer.

-

Diane Rosenstein: : Emma Webster

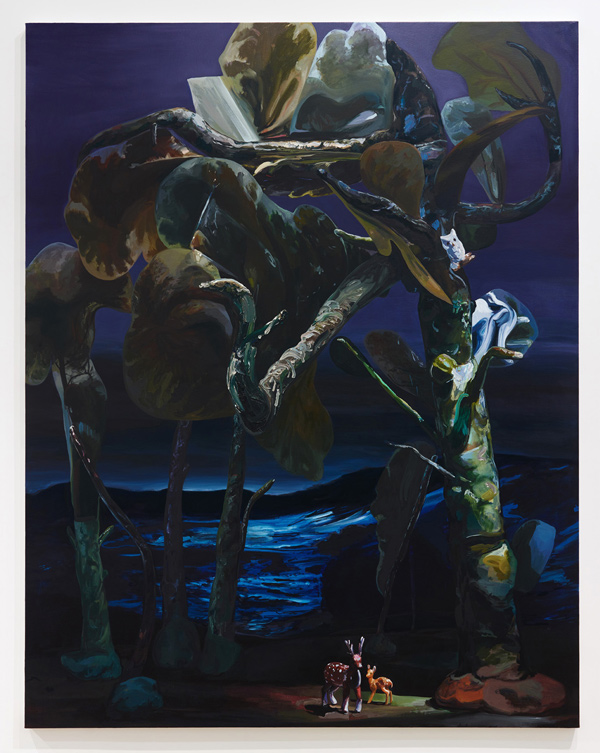

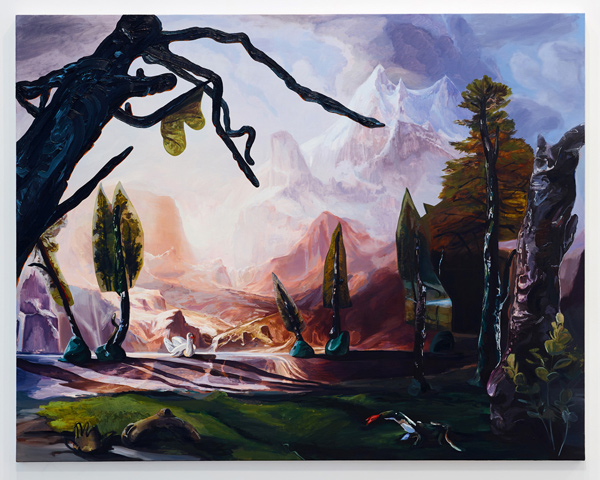

The 19th-century landscape painter Albert Bierstadt may have been a deer whisperer, able to corral an entire herd to pose for “Among the Sierra Nevada, California,” but let’s be real. The deer are fake.

In Emma Webster’s recent foray into landscape painting, she takes up art’s exalted tradition of deceit. Webster doesn’t paint nature itself, though, but depictions of nature; not a scene, but its construction.

Emma Webster, Still Life (2018), Oil on canvas, 108 x 84 inches, Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery. The paintings are of dioramas, where clay figurines and cut-out trees populate famous landscape paintings (à la Bierstadt or Claude Lorrain, for example), and harsh makeshift lighting casts shadows on twilit sky, breaking the illusion of pictorial depth and the sublime.

Conceptually, “Arcadia” positions itself with works like Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of Natural History Museum dioramas or Rodrigo Valenzuela’s time-dismantling photographs of photographs. Webster’s approach, though, has more humor than the gravitas of Sugimoto or Valenzuela, almost along the lines of Wayne White.

Emma Webster, The Hearing Forest and Seeing Field, 2018, Oil on canvas, 84 x 66 inches, Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery. Webster is most compelling when she takes full advantage of her medium. When it’s obvious that she’s painting a 2-dimensional cut-out of a tree planted in clay, the painting provides the same quick statement a photograph could. But when Webster obfuscates layers and blurs the distinction between elements, by a process only possible in paint, the force of the work comes not through statement, but through experience—the mind’s failure, and anxiety, over resolving what’s “real.”

Emma Webster, No Man’s Land (2018), Oil on canvas, 66 x 84 inches, Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery. Webster’s brushstrokes often have a certain uniformity in texture, dimension and contour –a clever strategy for solidifying disparate objects into a unified “space,” and for merging “space” with surface, but that uniformity has drawbacks, too. For example, some figures aren’t exactly realistically rendered, but are not unrefined or distorted enough to look intentionally so. This might not normally be an issue, but borrowing from famous “realistic” painters begs the question.

Emma Webster, Park Service (2018), Oil on canvas, 66 x 84 inches, Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery. Although “Arcadia” gazes heavily into the past, it definitely resonates with our present relationship with the artificial, which is ever increasing. Webster taps into this in her own vigorous, painterly way, and even though her humor seems to blunt the work’s own potential, “Arcadia’s” ersatz fantasies may still chart some new territory.

Emma Webster, “Arcadia,” February 9 – March 23, 2019, at Diane Rosenstein Gallery, 831 North Highland Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90038. dianerosenstein.com

-

Marie Baldwin Gallery: : Gary Brewer

Almost always, recognizing something as “beautiful” comes automatically, instantly—handed to you by a long function of evolution, culture and memory. Yet, at much slower rate, observation can generate a more conscious kind of awe, especially in nature, where hidden order unravels infinitely inward.

Through both of these perspectives, Gary Brewer seeks an aesthetic on the periphery of our understanding of the natural world. For example, in his latest show, “Infinite Morphologies,” Brewer paints coral, orchids and other vaguely organic objects adrift in billowy and translucent abstract forms.

If his goal is to prompt questions about the evolution and universality of natural forms, Brewer’s selection of objects is particularly effective. Brewer culls forms from micro- and macroscopic environments and pairs easily-identifiable objects with more ambiguous ones, illuminating curious similarities between disparate forms.

Gary Brewer, The Emergence of Form (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Marie Baldwin Gallery. The backgrounds in these paintings, according to Brewer, are based on imaging of dark matter, which would fit well into his theme of universality. It’s unclear whether Brewer intended to communicate this through the work, but it seems unlikely that the viewer could understand it without a hint. The backgrounds of his paintings still work, though, as their colors and contours echo the figures in the foregrounds.

In some of these paintings, Brewer includes only these background forms, and experiments with higher color contrasts. But Brewer is at his best with works like The Emergence of Form and Radiant Sublime, which—by including the foreground objects—display a fuller range of Brewer’s technical abilities and provide better arguments for his commentary on universal forms.

Gary Brewer, Constellation (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Marie Baldwin Gallery. Brewer picks an interesting time to focus on questions of beauty in the natural world. Nature may be art’s oldest subject, but the contemporary art world seems increasingly less interested in questions of beauty, whether by literal representations of nature or by attempts to recombine its patterns to evoke those elusive “automatic” responses.

Admittedly, if slow forces like evolution, culture and memory limit us to what we automatically find beautiful, perhaps art’s challenge is in presenting a new value system to match our exponentially complicating world. But Brewer raises, implicitly, a persuasive response: for every question answered about the natural world, a new, potentially deeper one takes its place.

Gary Brewer, “Infinite Morphologies,” January 6 – February 3, 2019, at Marie Baldwin Gallery, 814 S. Spring Street, Suite 2, Los Angeles, CA 90014. www.mariebaldwingallery.com

-

Michael Maxwell

In the mixed-media works of his exhibition “Neo-American Transcendental,” Michael Maxwell employs materials ranging from the prehistoric to the digital. Clay, natural mineral pigments, plant dyes, wheat paste, quartz crystal, silver and gold leaf, beeswax, encaustic, and oil and acrylic paint, are all applied on top of, or amongst, digitally-created scenes or patterns. Viewed as a maximalist’s take on primitive mark-making or a historically-minded Abstract Expressionism, Maxwell’s work deserves attention, but where his work truly stands out is in his handling of the digital. Like other artists who have successfully incorporated it into their work, Maxwell’s is not “about” the computer. Maxwell takes the computer—one of the biggest influences on contemporary art and painting—and folds it into something earthen and materially complex, brilliantly enhancing our sensitivity to it.

In several of his works, like Blue Hole Excursion (2018), Maxwell has “painted” onto large prints of nature scenes. They’re not simply photographs, though. The scenes are digitally-created composites of smaller images and it’s clear he wants you to see the stitches of the minor misalignments. By transitioning his brushstrokes from appearing flat on the surface to entering the third dimension of the photograph, Maxwell pulls the digital construction of space into his shamanistic stirring of materials. In other works, like In the Morning Light Many Things Seem Possible (2018), he’s affixed cutouts of digitally-produced patterns to his compositions—there, too, the direction and texture of his brushstrokes respond to the patterns of the digital prints, appearing to vibrate at resonant frequencies. Even when he’s not literally using the digital, his works subtly reference its aesthetic: often they feature groups of parallel marks that seem to align to an invisible structure, just barely suggesting a loose or nascent grid.

Michael Maxwell, Visual Primitives, Constellations (2017), courtesy Garis & Hahn. Maxwell situates his digital elements beautifully amongst other dynamic features and textures of pivoting functions. His loose-grid marks resemble rudimentary symbols, especially when they intersect to form crosses, asterisks and diamonds, which jangle as they hang askew in space. Many marks also appear to glow or expand, due to their soft edges and multiple outlines of successive color. From afar, the surfaces look like they have been eroded or torn away, but at the same time, especially in Tiffany (2018), the proliferation of marks appear to have overgrown the bones of an underlying image, almost like a corrupted digital image might leave behind remnants of a visual structure.

Emerging alongside the varied effects of his surfaces, the mold and dust of his palette, the glitches and electric pink, and the religious glow of gold leaf, is a strong sense of prehistory and of the human story. The digital, in Maxwell’s vision of the natural world, shares the same space as earthen and old-world materials, which are literally cracking on the surface and crumbling off the canvas. Under the trance of “Neo-American Transcendental,” the digital—the non-physical realm where we store our lives—slowly slips into tomorrow’s old dreams.

-

RODRIGO VALENZUELA

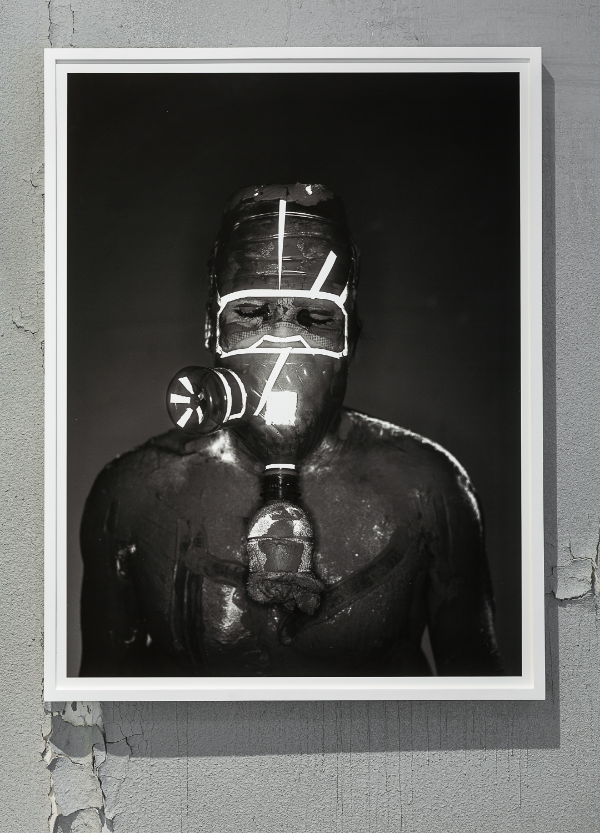

Named after Pablo Neruda’s epic poem on the history of the Americas, Rodrigo Valenzuela’s own “General Song” harmonizes with its Lantinx perspective; his two series of photographs, “Barricades” and “Masks,” confront social issues like immigration and revolt while meditating on the medium of photography.

The primer-white and paint-chipped scenes of “Barricades” exist in simultaneous construction and dismantling, both in material and in concept. The foreground objects of “Barricades” build off, and extend into, a large photograph affixed to the wall, showing how they were arranged in a previous moment (captured in the photograph). “Barricades,” a series that ruminates on the artistic process and object perception, raises more nuanced questions about photography and complicates our relationship to it.

Even though the mechanics of a photograph (recording a single moment) make it resistant to showing the sequence of its own becoming, Valenzuela’s “Barricades” exhibit an artistic process we might expect of other, physical media, but still maintain the temporal precision characteristic of photography. The inner and foreground scenes, with their reused and rearranged objects, suggest a brief increment of time, yet their objects rest on each other as if no time separated them at all. “Barricades” are simultaneously breaking the moment in two and mending it back together.

Rodrigo Valenzuela, Mask #3, courtesy of the Artist and Klowden Mann, Culver City, photo by Matthew Farrar. Photography, too, maybe because it can preserve a moment otherwise lost to time, carries with it a certain sentimentality, or at least the blueprint for it. As a photograph is intended to store visual information as close as possible to our own visual experience, the more accurate the photograph, the more it invites the viewer to enter its space—to reclaim a past moment. “Barricades” sabotages that natural response. The series leads the eye, tricks the mind, and asks the viewer to step inward through the planes of the image, into the interval of time suspended between the foreground and inner photo (perhaps even into the solitary realm of the artist’s process). But at the same time, they obstruct. In the details in the periphery, Valenzuela deliberately reveals the illusion, almost forcing us to admit: we want to be deceived.

In both “Masks” and “Barricades,” Valenzuela employs art’s unique ability to connote multiple ideas and feelings without actually declaring what it is, or even being something at all. And he orchestrates those connotations in such a way that the interactions between them create the ineffable experiences that his audience, as art-makers and viewers alike, should seek out of art. With “Masks,” a series of tenebrous but electric portraits of mud-covered men wearing makeshift respirators, Valenzuela somehow achieves this with political and social issues, where voices are often so strident that they stifle the viewer’s ability and willingness to explore or experience different ideas—especially in today’s political climate. While others might equip politically-charged objects to incite, Valenzuela’s mastery of detail and ambiguity instead cultivates a sensitivity and awareness. In an air of riot and ritual, “Masks” enables the viewer to commune with the subjugated and the defiant, the hopeful, the indigenous, the dead.

-

ACE:

Gary Lang

Gary Lang’s circle paintings, perhaps the most monumental of his oeuvre, might be the most intimate, too. “Rising,” his current exhibition at Ace Gallery Beverly Hills, includes a number of these pieces, as well as other works from the past 10 years, and a group of new paintings. Each circle painting records Lang’s meditations on color in concentric rings, condensing sfumato and swings of mood, moments of control and the marks of each brushstroke. Every color and cognitive state Lang painted and experienced over the course of making these paintings coalesces into a massive illusionistic object, generating their own gravitational pull, and inducing a state of vertigo. While they are experienced as physical and monolithic from afar, they remain delicate and fleeting up close.

Gary Lang, “Rising,” installation view (Water Twister and Water #2), courtesy of the artist and Ace Gallery. Water Twister (2010) and Water #2 (2007), like Lang’s circle paintings, deliver a cumulative effect, but without the gravitational center. This (literally) de-centered approach poses questions about consciousness, as if Lang’s thought process had become unhinged, and spread through a Petri dish. The fluorescent, dark electric colors of Water #2, for example, sprout into coral shapes or interlocking flora, twisting together a sense of tropical and bacterial.

Gary Lang, “Rising,” installation view, courtesy of the artist and Ace Gallery. Lang’s meditations in color can be enjoyed as purely physical experiences, but can also, as with his word paintings, demand reciprocal patience and devotion from the viewer. The text of these paintings contains no spaces, and lines break in the middle of words. Whether the viewer lets the words bubble up, or pieces together the whole phrase, it’s an act everyone is privately familiar with: extracting clarity and truth from the opacity of thought, where language can be clouded by the haze and color of emotions.

Gary Lang, Rising (2015), courtesy of the artist and Ace Gallery. Rising (2015), the show’s centerpiece, is a new style for Lang, but has the same emotional and sensory complexities as his other work. This towering, 19-by-12-foot grid of 24 paintings looks arm-deep with overlapping propeller shapes and their individual parts. It has the weight of scrap metal piling up, but the delicateness of flower petals slowly falling. It’s somber but somehow blooming with color. Approaching it feels like walking into a column of ash and confetti—just one of the many contradictions and improbabilities that Lang so convincingly makes visceral.

Gary Lang, “Rising,” September 10 – November 12, 2016 at Ace Gallery, 9430 Wilshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills, CA 90212. acegallery.net

-

MIM Gallery:

Allusive Moment

In “Allusive Moment,” a group show centered on nostalgia, a slow creaking sound fills the gallery and precedes—even preempts—visual encounters with works in the show. The creaking sounds like it might come from the wood beams or floorboards of a childhood home, except it is rhythmic, as if from the hull of a ship straining in an ocean swell, imparting the idea of a journey.

Keyvan Mahjoor, Untitled (2015/2016), courtesy of the artist and MIM Gallery. The creaking is part of Farhad Kalantry’s video installation, Places (2015), which is made with a single shot down a long corridor of shifting wood-floored rooms. Places imbues “Allusive Moment” with something more than the traditional themes of nostalgia. While this group show draws on the capacity of common objects to hold memory, and balances the weight of the past with the intimacy of the moment, it also—because nostalgia is also subject to the mind’s tendency to distort—drifts into the surreal.

“Allusive Moment”, installation view, courtesy of MIM Gallery. Similarly, Keyvan Mahjoor’s ink drawings of somber but dreamlike scenes play like a threnody, with the weight of their shadowy figures and the levity and rhythm of swirling calligraphy.

Shiva Aliabadi, Safety of Objects III (2015), courtesy of the artist and MIM Gallery. While some pieces in “Allusive Moment” conjure reverie, others create a sense of immediacy or enshrine the hardened exactness of a moment. Shiva Aliabadi’s “Safety of Objects” series, for example, resembles Louise Nevelson’s monochromatic, tightly arranged compositions of household objects, except there is a suddenness to them, a disarray or vague sense of panic, that has been vacuum-sealed and preserved.

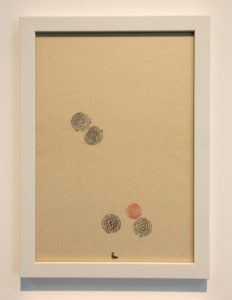

Farshid Larimian, Coins (2016), courtesy of the artist and MIM Gallery. Farshid Larimian’s Coins (2016) also records instantaneous moments, but through the act of rubbing a coin’s image onto paper. Coins carry known and unknown history: their low-relief images commemorate significant figures or events of a culture, but they travel through the day-to-day, hand-to-hand moments, dulling over time, but storing experience by virtue of their durability. The three compositions of Coins are cleverly hung lower on the wall. The viewer has to crouch to examine them, as if its contents were kept in a drawer along with other old items. Like the low entrance of an old temple might force its visitor to bow down, Coins demands another action: an emulation of rummaging, and reminiscing.

“Allusive Moment”, installation view, courtesy of MIM Gallery. Farhad Kalantary, Shiva Aliabadi, Keyvan Mahjoor, Farshid Larimian, Shirin Attar, Samira Hodaei, and Afsoon, “Allusive Moment,” June 18 to July 23, 2016, at MIM Gallery, 2636 S La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles, California 90034, mim.gallery

-

Mark Moore Gallery:

Christopher Russell

Christopher Russell has made several series of works by scratching the outlines of objects or patterns into photographs of dreary nature scenes, empty domestic interiors, and even high-contrast images of lens flare. In his latest show, “Ersatz Infinities,” Russell continues to explore the relationship between viewer and image, but he now broadens his investigation into the territory of digital imagery.

Christopher Russell, The Falls XXX (2016), courtesy of the artist and Mark Moore Gallery. Unlike with his previous work, the base photographs of “Ersatz Infinities” have only traces of scene, subject or object. Each photo is washed out, filtered into a monochrome. Harsh lens flare has been subdued into a gentle scattering of light. But as the original image drifts into immateriality, floating somewhere between physical space and pure color, the work prompts us to ask new questions about sensation and the experience of place.

Christopher Russell, The Falls XXXIII (2016), courtesy of the artist and Mark Moore Gallery. In the scratched images of “Ersatz Infinities,” Russell is no longer adding objects into the physical space of the underlying photograph, or playing off of their features, but seems more interested in the compression of depth and space into a single surface or screen. The flat, polygonal landscapes and geometric abstractions of “Ersatz Infinities” often include patches of stippled images, where a grid of marks in varying thicknesses indicate depth, light and space. However, in the cold numerical precision of the spacing and placement of each mark, is an intimate moment, a record of human touch. Russell creates these moments in larger compositions too, by making imperfect copies of otherwise identical images, as in the side panels in The Falls XXVII (2016).

Christopher Russell, The Falls XXXV (2016), courtesy of the artist and Mark Moore Gallery. Russell once expressed that when he started working with digital printing, part of the “preciousness” of the medium of photography seemed to disappear. Maybe this also applies to a general trend in photography, but as Russell’s images become more digital, it’s as if Russell is trying to hold on to something for us, even if it is only through small, delicate acts of violence. To whatever extent there is a sense of loss, Russell’s work evokes complex feelings, tensions and aesthetic considerations.

Christopher Russell, The Falls XXIX (2016), courtesy of the artist and Mark Moore Gallery. Christopher Russell, “Ersatz Infinities,” April 16 to June 18, 2016, at Mark Moore Gallery, 5790 Washington Blvd., Culver City, California 90232, www.markmooregallery.com.

-

Royale Projects:

Karen Lofgren

The sculptural objects and installations of “Other Relevant Experience,” with their ceremonial shine and talismanic power, exhume dark histories of conquest and ruin while conjuring notions of magic, sacrifice and salvation. Karen Lofgren’s command of materials and their historical significance enables her to achieve these rich, diverse connotations, often with simple designs. For example, the felt loops of Leaning Figure (all works 2016) and Feedback Feedback Feedback appear petrified and damp, as if recently unearthed, but also look slightly industrial, like fatigued rubber.

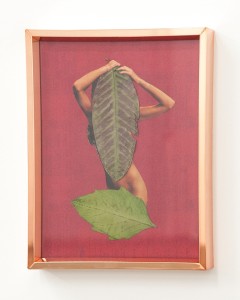

Karen Lofgren, Feedback Feedback Feedback (2016), courtesy of the artist and Royale Projects: Contemporary Art. Photograph by Sabina McGrew. Lofgren frequently revives ruin, or casts old objects as new. “Other Relevant Experience” includes a corroded steel spike that has been copper-plated, and copper casts of fingers, which look severed and cadaverous, but with their opulent metallic luster, imply social status and sacrifice. There is sometimes even a humorous, but still disconcerting, combination of themes of salvation and conquest. In the series, “Could You Name What is to Cure,” Lofgren’s copper-framed idols of tanned, bare-limbed and anonymous figures conflate the indigenous with the pornographic, and the medicinal with the perverted.

Karen Lofgren, Could You Name What Is To Cure #3 (2016), courtesy of the artist and Royale Projects: Contemporary Art. Photograph by Sabina McGrew. The objects are never purely archaeological though. While Lofgren can draw from the history and power of artifact, they’re ambiguous as to time and place, often blurring notions of past and present, aboriginal and industrial. Symptom and Under Influence, for example, combine anachronistic methods: Lofgren has raggedly stitched together animal skins, but they’ve been garishly dyed, upholstered in the shape of a cylindrical arc and end-capped in copper. Lofgren’s sculptures are more than just history, but history unraveling and weaving into familiar experience, sometimes as a suture for the past, sometimes making post-apocalypse more present.

Karen Lofgren, Other Relevant Experience (installation view), courtesy of the artist and Royale Projects: Contemporary Art. Photograph by Sabina McGrew. Amid evocations of ritual and ruin, Lofgren’s work makes the viewer acutely aware of the presence of his or her own body, but also eerily aware of absences. This is especially true with “Approaching the Limbless Gods,” a series of three large white blocks, each hollowed out in the shape of a human torso, like a mold. But the dark interiors of these molds have no details from any particular imprint; their sinuous curves have been smoothed over and rounded off from repeated use, as if many people had pressed their weight into them. Lofgren uses the repetitive implication of the molds to cleverly play into the idea of ritual, that is, the repeated acts that transmit and slowly distort belief and identity. The mold’s smoke-gray grooves summon the viewer’s body into the ash and repetition of ritual, but apparitions—the absences implied by the molds—are just as present.

Karen Lofgren, “Other Relevant Experience,” April 2, 2016 – May 14, 2016, at Royale Projects: Contemporary Art, 432 South Alameda Street, Los Angeles, California 90013, www.royaleprojects.com.