What does it mean to fall from grace? To really fall, from great heights, perhaps at first thinking you’re flying and only realizing too late that this was an illusion, probably induced by the drugs. That would explain why the world out there appears so eerie, so pink and gold, so velvety, so noir-ish. Still, it’s beautiful in an afterlife kind of way, the damp night air, the hot wafting breeze, the sickly, sparkling city lights in the distance, the moon skipping across the water, the neon pooling in the pavement far below. Damn it. Seems you’re falling after all. If you try hard enough, perhaps you can freeze this moment, pause time and create a pocket universe in which questions of falling or flying become obsolete, and there is only the question of floating inside this moment. Yes, that’s better. Let’s do that instead. Forever.

“Robert Yarber: Return of the Repressed” includes both brand new (2018) and selected earlier (1985–93) large-scale paintings, and marks his first solo show in Los Angeles in more than 20 years. He’s been living and working here while on sabbatical from his teaching position at Penn State. Yarber became an international art world favorite following his inclusion in “Paradise Lost/Paradise Regained: American Visions of the New Decade,” an exhibit organized by the New Museum for the American Pavilion at the 41st Venice Biennale in 1984. Yarber gained further prominence with his inclusion in the 1985 Whitney Biennial. His paintings were exalted as both contrarian and emblematic with regards to their cultural milieu and aggressively anti-trend, retrograde variations.

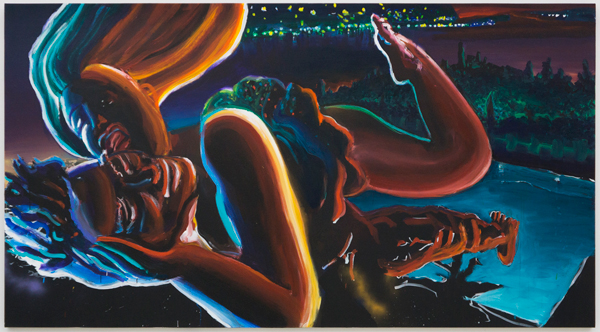

Gas and Limited Oxygen, 2018, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 132 in., Courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, Photo by Lee Thompson

This was, after all, the Reagan era, a time in geopolitics and urban economics that incubated both the bedazzled Wall Street aspirations and concurrent angry punk rock complaints. Yarber himself experienced then and still retains a personal ambivalence about painting not being “cool.” He vividly if not fondly remembers that time at Cooper Union when “Hans Haacke told me I was a loser. I was 20!” But Yarber knew even then that Haacke’s was some kind of twisted compliment, an acknowledgment at least of Yarber’s nascent neon-tipped, pigment-laden rebellion; a recognition that he was in fact taking a stand against the bloodless dominion of critical theory—by painting pictures of people enacting sexy, emotional narrative allegories.

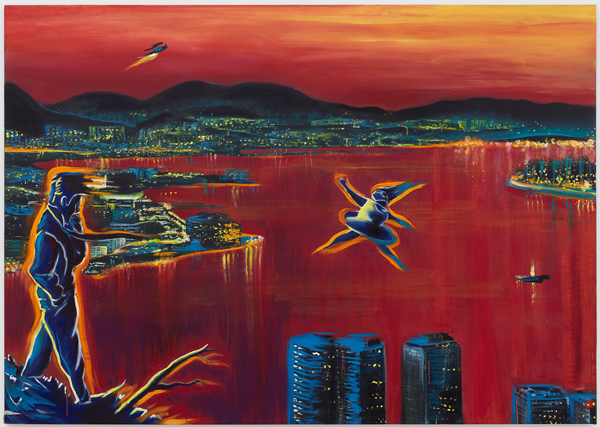

Error’s Triumph, 2018, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 132 in., Courtesy of the artist and Nicodim GalleryPhotograph by Patrick Kellycooper

Yarber proceeds with a palette and a parallax sense of lighting that evoke the kitsch of black-velvet paintings, the existential threat of a high fever, and a certain music-video sensibility that was all so very 1980s—remember, MTV was launched in 1982. But in works like Error’s Conquest (1987) and Error’s Triumph (2018), we see that this chintzy, pricey promise of luxury, the fad for hotel living, the resurgent myths of Las Vegas and Atlantic City—and in the drug-induced euphoric levitation of 2018’s Gas and Limited Oxygen that leaves his characters, as the gallery states, “suspended within a transcendental aspic”—that all of this is no longer retro. It’s back; we are reliving the vicissitudes and vanities of those times anew, yet with a unique sense of danger, because this time the stakes are higher. These things are true not only in the culture Yarber depicts, but in his own practice of rendering the dynamic.

Vista, 2018, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96 in., Courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, Photo by Lee Thompson

As Yarber takes up this stylistic mantle afresh, he is cognizant not only of what has happened in the world in the decades since the last engagement with these issues, but also in his own life, and in art history. The new paintings are recognizable, yet their transcendence is now tinged with urgency. This could be political of course, and societal, as ever—but there’s something about the new paintings that makes the dimension of self-portraiture (both in image and in psychological avatar) more overt and poignant. He’s the one who brings up Freud after all, right in the show title.

Lustily, luridly and laughingly evoking both nostalgia and its opposite, Yarber’s dominant figurative motif is a sexually engaged cisgender couple. Yarber does speak at length about his gorgeous and interesting parents, and it’s tempting to see that psychological construct as a kind of pas de deux of enchantment and disillusion that has subsequently informed Yarber’s romantic surrealism. Influenced by cinema, especially the denaturalized space and lighting that one finds in film noir, Yarber is forever pushing up against what is impossible versus plausible. Blind in one eye since birth, he knows he’s seeing it “wrong” but that just means that in these soft-core phantasmagorias he’s only painting what he sees. The flatness, the compression and expansion of pictorial space, and the dream-logic phenomenology of internal cohesion despite intense weirdness all contribute to creating a masterful externalization of a set of internal realities. Freud would be proud.