This past August I decided to brave the coastal traffic to make a visit to the Lux Art Institute near San Diego. I was on deadline and woke up with a cold, but I had been notified that mega-artist and LA expat Jorge Pardo was scheduled to speak as his artist-in-residency time was winding down.

I had encountered Pardo a year before, at his new home base in Merida, Mexico, when he had graciously hosted me for an extended sit-down interview. I’d been looking for a chance to follow up, and this looked like just the opportunity.

Pardo, best known for his decorative sculptural lamps and houses-as-art projects, is in great demand now. He flies all over the world with commissions from wealthy art collectors to design and build houses. He is currently in the 57th Venice Biennale, has a solo show of new paintings (yes, paintings), up until January with Petzel gallery in New York, and is completing a castle-cum-hotel in the south of France. What luck, I thought to myself, to catch him in Southern California.

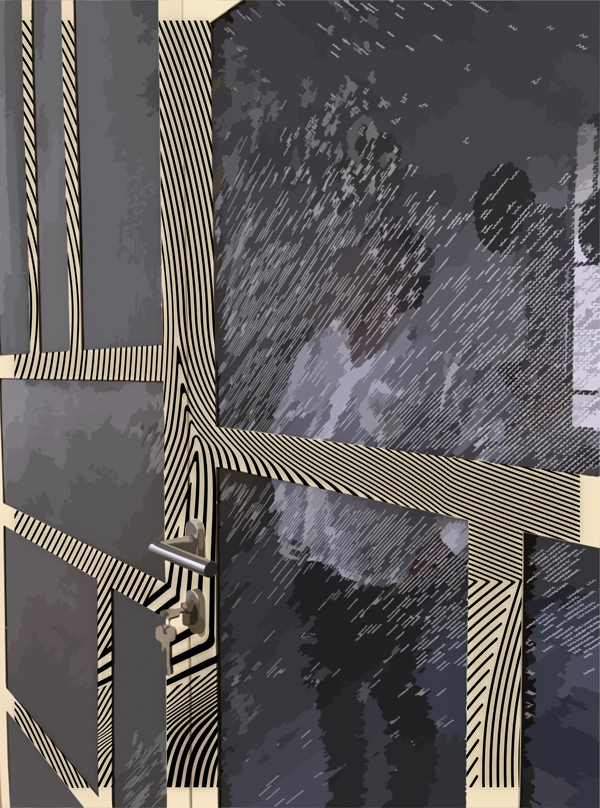

Pardo’s installation, courtesy Lux Art Institute.

Upon my arrival at Lux I discovered that Pardo had gone MIA. He was supposed to have been there three days earlier and no one had heard from him. “Why wasn’t I told?” I calmly asked, ready to scream as I was feeling more and more lousy with my cold coming on. Obviously in deep denial, the staff had hoped he might still show any minute. (One employee explained that Pardo was a pilot—as if he might suddenly appear out of the sky swooping in for a landing on the institute’s vast grounds.)

Pardo didn’t show that day, or any day after. His project as artist-in-residence was actually done by an assistant he flew in from Berlin, and the show was de-installed without any fanfare.

Jorge Pardo with his installation at Lux Art Institute, 2017, courtesy Lux Art Institute.

Did Pardo shirk his responsibilities as an artist-in-residence? Maybe a bit. But Lux did get their show and Pardo did make an appearance. Pardo’s behavior could be seen as just another ordinary arrogant art star. But the few times I’ve been in his company, he did not seem arrogant at all. In fact, quite the opposite.

MERIDA, MEXICO

I met Pardo at his studio in Merida just over a year ago when my husband and I were traveling in the Yucatan. A friend suggested I look up Pardo while there. I’d only met him once, long ago at a dinner party in LA. I remember he was easygoing and even asked me questions about myself.

His art, or the way he makes art, has always intrigued me, while still leaving me a bit ambivalent. His work borders on the decorative with his sleek cabinetry, homogeneous pastel colors and fanciful but functional lamps. His house projects, where he builds an entire house, top to bottom, as well as designing the grounds and interiors, seem like ostentatious architecture for the rich and famous. Perhaps if I got to know the artist some of my wavering about his work might get resolved. I felt it was a long shot to interview him, but since we were there in this wonderful tropical city, why not?

Pardo responded in an email through his assistant with an invitation. My husband accompanied me to his studio. A large industrial garage door was open when our cab dropped us off in the part residential, part commercial neighborhood. Since the door was open, we walked into an industrial workspace filled with heavy equipment and moving forklifts, clanging and buzzing echoing all around. A young man stopped his hammering when he saw us and led us to Pardo’s office.

Entrance to Pardo studio, back room leads to more spacious workspace, photo by Tulsa Kinney.

We entered a large separate room cut off from the noise and chaos of the workshop area. Inside we passed two rows of Macs with several young people intensely occupied as we were led to a long table toward the back wall to wait for Pardo. We sat there for a while, in silence, admiring the 3D wallpaper pattern directly in front of us, a design obviously by Pardo: yellows, reds, ochre and orange, red-browns and yellow-greens. It was hot that day, and we were thirsty, but no one offered us water.

Pardo appeared moments later, wearing a cream cotton button-down shirt with lime-colored chinos and flip-flops. Curly salt-and-pepper hair framed his white-bearded face with bushy dark eyebrows accenting his squinty brown eyes. He moseyed over to the table and set down his coffee and cigarettes. He had a friendly face and smiled easily, though he hadn’t said a word yet. As he sat down across from us, he leaned in, looked directly at us and said, “So what’s going on, guys?”

Pardo at his studio in Merida.

He couldn’t have been more welcoming or affable, putting us at ease immediately. “Is there an art scene here?” I asked of the Mexican Yucatan capital he has been living in for several years. Pardo answered directly, “There is no art scene.” He repeats, “there is no art scene.” “So is that why you’re here?” I ask. He contemplates, “I guess, not strictly because of that, because I participate in other art worlds and am in and out frequently enough that I don’t feel like I have to get away. It’s just a calm nice place to live. I like the heat. I love the tropics. It reminds me of Cuba, where I was born.”

Pardo closed up his Los Angeles studio with all his belongings five years ago. “I said, ‘I’m leaving, whoever wants to come, please sign up.’” He didn’t want to live in LA anymore, although he did invite his studio employees to join him with their same jobs and salaries. “Nobody came,” he laughed.

Jorge Pardo, Tecoh, 2012, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

But moving to Merida didn’t happen overnight. Pardo’s first commission in the Yucatan was to refurbish a project called Tecoh, an old rope hacienda deep in the Yucatan jungle, about an hour’s drive from Merida. He spent six years on the house project, traveling back and forth from LA. His need for temporary residency eventually led to a permanent situation.

Born in Havana, he was six years old when his family moved to Chicago, and that’s where he grew up—so much for the balmy weather he now desires. Pardo knew he wanted to be an artist early on—he made things: “Stuff like this junk.” (He picked up a mysterious object on the table to illustrate.) “I remodeled my parents house from when I was 13; what I got for my birthday was a table saw.” We laughed at the startling idea of a 13-year-old working with hefty machinery. His neighbor was a “really good carpenter,” while his dad was a “real grump and alcoholic” (he said this matter-of-factly, with a chuckle). “I would tear down the walls, go to the library and read books and learn how to frame, learn how to make things, do sloppy electrical work.” He laughed again.

Pardo attended the University of Illinois and majored in biology. He switched to art after taking a painting class for fun; his teacher suggested he change majors and he ended up at the Art Center in Pasadena in 1984. The undergrad program was small back then; many undergrads and grads might be in the same classes and art shows. The faculty consisted of several CalArts refugees fleeing to Art Center after a political dust-up. Richard Hertz, along with Stephen Prina, Chris Williams and Mike Kelley were there when Pardo became an undergrad.

“Everything was highly theoretical; I loved all that crazy French theory that we were force-fed. Actually I could understand it, the rest of the other kids were retards and they just kind of thought it was something you needed to have in order to substantiate your work. And I enjoyed that,” Pardo says with a certain bravado. “They used to call us post-studio artists. I remember Jeremy [Gilbert-Rolfe] coming in 1984 and saying, ‘We’re going to make a really great attempt to make the best post-studio program in the country.’”

Pardo does seem to embrace the post-studio practice, which refers to the way an artist works, for instance with collaborators, on laptops—not the traditional artist working alone in their studio. With only a BFA, Pardo was basically thrown into the art world right afterwards. “I was lucky. I had done some work in school that got a lot of attention,” he said rather modestly.

His prof Stephen Prina introduced him to Thomas Solomon. Solomon visited Pardo’s studio twice in two years, which eventually led to a sold-out solo show in 1990 at Solomon’s gallery, The Garage in West Hollywood. LA Times art critic Christopher Knight lauded the show. Pardo was dazzled by all the attention—and money (more than he made in a whole year at his other job, he pointed out). “I ate arugula for the first time,” he says with a laugh.

4166 Sea View Lane, 1998, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Five years into his young career, he found himself being offered a MOCA show in the project space. “I thought to myself, ‘Let me do something that is bigger than that space, but connected to that invitation.’” That something bigger became an actual house, titled 4166 Sea View Lane (1998). Propped on a hillside in Mt. Washington, a community on the edge of downtown Los Angeles. When the exhibition ended, Pardo moved into the house to live; 20 years later it remains occupied by his relatives.

When I first heard about Sea View Lane, I remember thinking this artist has cast a spell on the art world. I wasn’t convinced it was art. Maybe Pardo was a con artist rather than a post-studio artist or whatever else you might call him.

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

One of the burning questions I had for Pardo was I wanted him to tell me how Sea View Lane was art, and not simply sleek architecture and tasteful décor. But all he wanted to talk about was “problems.” He referred to Sea View Lane as a “discursive machine” and how the changes that the museum would have to go through in staging the exhibit was the most interesting part of the piece for him. His answer suggests the process is where the art part is.

Jorge Pardo, 4166 Sea View Lane, 1998, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

“I like the word ‘problem,’ because a problem is interesting. If you have a problem, you have to fix it. You have to work through it. You have to invent stuff. You have to change your mind sometimes. You have to bring in people to help you understand the problem. I use it that way,” he said, finally lighting the cigarette that had been dangling from his mouth for several minutes. “I like things that are strange and funny; I like the way jokes work, why they are funny and why they’re not.” And I’m starting to wonder if Pardo is playing a big joke on the art world.

So Pardo designs and builds houses and calls them art. They are wonderfully imaginative and aesthetically pleasing. Many architects could say that too. Take Frank Lloyd Wright or Richard Neutra—of whom Pardo is a big fan—no one can deny that their houses are works of art. Yet Pardo maintains he’s not an architect. “I do a very particular type of architecture. I do, uh, kind of a quasi-architecture, almost like folk architecture in a way.”

Pardo hires professionals, of course, and works side by side with all the workers on the structure. He claims to know a lot about building, but many times there are no blueprints or programs. He doesn’t churn out one architectural project after another; he may do three in one year, but then none for several years. Thus far, he’s done eight.

Exterior of hotel maquette in Pardo’s studio, photo Tulsa Kinney.

Patterned floors of the hotel maquette, photo Tulsa Kinney.

And right now he’s embarking on his biggest architectural project of all, The Hôtel d’Arlatan in Arles: an ancient castle in the south of France that he will renovate into an upscale 40-room hotel. He points to a maquette over to the side and asks us to take a look. It looks like an old haunted mansion, painted dark brown on the outside, with brilliant patterned floors inside, and windows like portholes. The floors will move and change colors. But is it art?

What may have been Pardo’s first art project was deconstructing the house he lived in, when he got that table saw for his 13th birthday. Can you imagine a mere teenager tearing down a wall of his home while the family still lives in that space? Was he tearing apart or rebuilding his home? He had mentioned his alcoholic father so dismissively that I was left wondering about his motives.

Jorge Pardo, Untitled, 2013, Set of Five glass lamps, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

His cynicism for the world is deeply hidden in the beauty and decoration of his work. When he came to LA to make art, the city made an impression on him: “When I was in LA, I realized there’s no real art in LA; the only thing that we had that was historical and cultural were these old buildings that people made a hundred years ago, and they are still there. We don’t have our Picassos, we don’t have our Monets, we don’t have our Greek stuff, but we got this, and that’s real. There’s a really interesting logical historical development that turns these things into being. That to me is a culture that, as an artist, I can use to represent what it’s like to make work if you live here.”

Jorge Pardo, Self Portraits (Crackel Lamps), 2017, courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

So, blame it all on LA? If not for LA, would Pardo have made Sea View Lane? Would he have made his lamps if he hadn’t browsed LA thrift shops? It does seem plausible that Los Angeles had a profound effect on his art. Pardo started ranting, about Europeans, New York, even painters got equal lambasting. “You know, painters, they’re crazy people. They paint this shit. Instead of saying it’s made out of this, and it’s got this on it, they think there’s some fricking gas coming outta it.” We all laughed at Pardo’s excitement. He then backtracked a little, “That shit’s great, but it’s like contemporary art has to be more special than that. It has to be more about the real, in a way that is much more complicated.”

Jorge Pardo, Self Portraits, 2017,courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York (now showing at Petzel gallery).

Complicated, Pardo is. A year ago he was making fun of the practice of painting and now he’s exhibiting a new series of his own paintings. I like Jorge Pardo as a person, as someone to have a drink with and talk about the art world. And I believe he’s an artist. He thinks and sees like one. I’m still wavering on whether his work is really art. I’d love to have one of his cool lamps in my house, and I wouldn’t mind living in a house that Pardo built. His new paintings are up now in a gallery in New York. So, what’s my problem?