Post York

Story and Art by James Romberger

with additional material by Crosby Romberger

112 pages

Dark Horse Comics/Berger Books

“They somehow set fire to what was left of the East Side.”

—POST YORK, p.86.

The city had been ceded to climate change. It was drowned, abandoned, gone wild, given over to the feral young: a hostile, black-and-white environment, prone to violence but still susceptible to love. It was POST YORK.

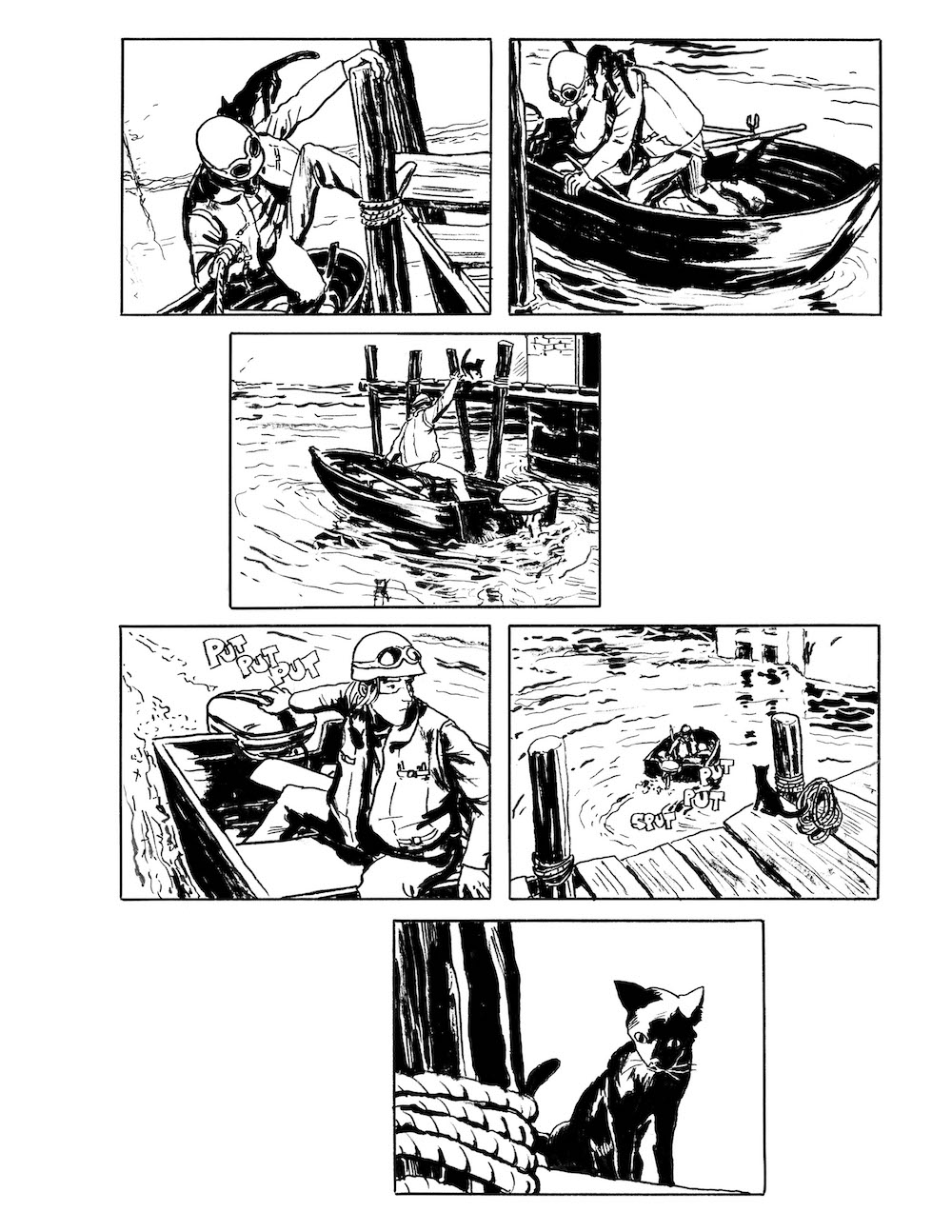

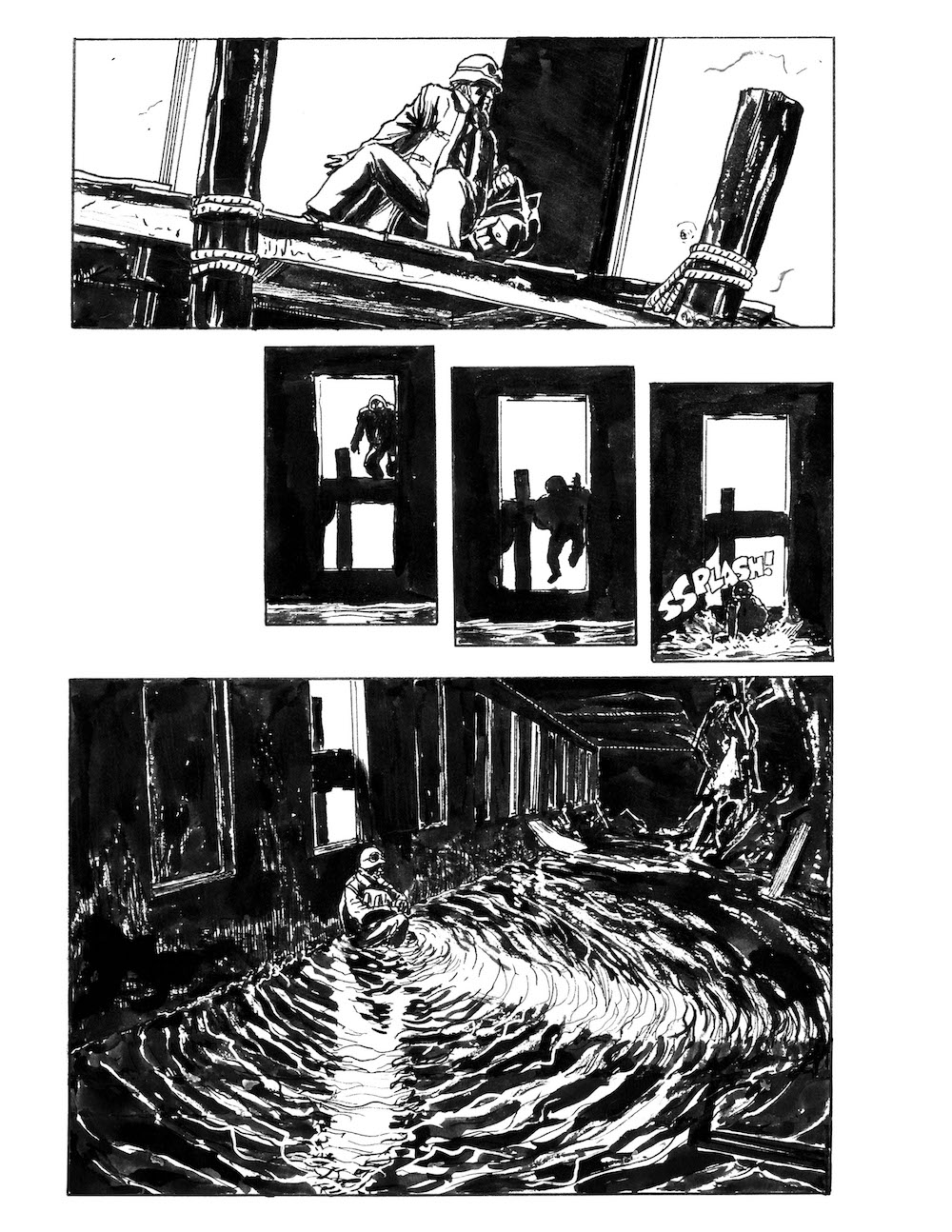

POST YORK is a graphic novel of striking immediacy, a near-future dystopia with an in-your-face punch. Lacking all the context that might characterize a contemporary climate disaster newscast, the novel begins quite simply, as an adventure in daily living in the flooded ruins of a post-apocalyptic New York City. Crosby, the novel’s protagonist, searches the submerged city in a dinky motorboat, rustling food for his cat, Kitski. He finds a cache in a deserted movie theater inhabited by a pretty young squatter named Ivy. She confronts Crosby. They fight. An uneasy truce ensues, sealed by an act of accidental barter. Ivy smiles as she admires her new helmet. Crosby heads home to the hungry Kitski.

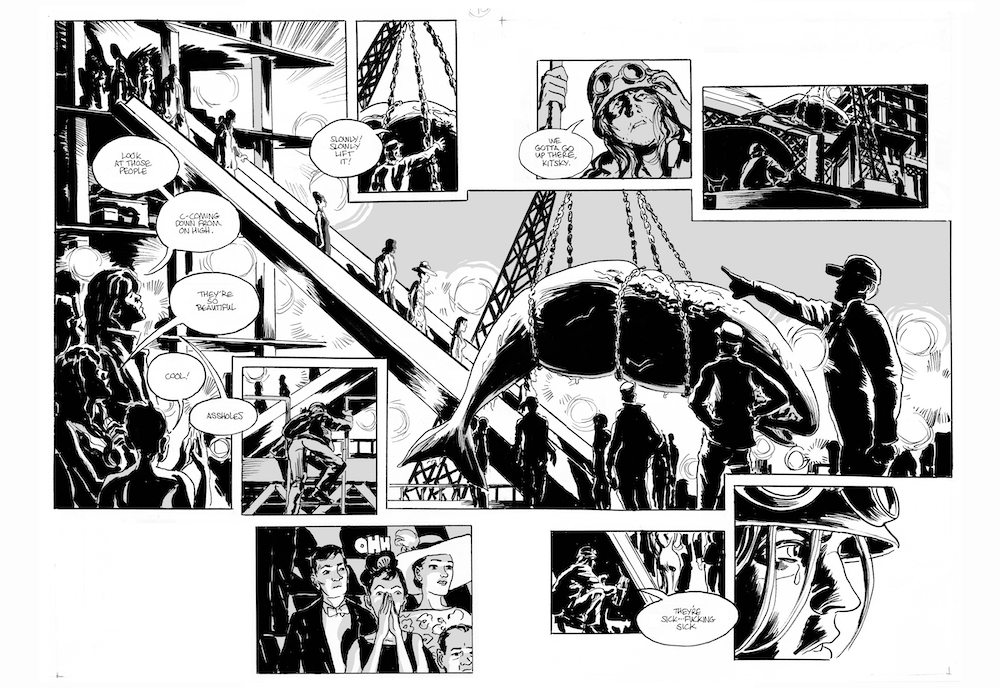

Page 5 from POST YORK

However, several subsequent panels of rain pouring down on empty exteriors suggest a more malign reality. The city’s only denizen appears a lonely and bedraggled pigeon, looking very like Noah’s land-seeking dove, perched on a sleek light stanchion. And there is no respite from the deluge.

Rather, this low-key narrative becomes the template for a thrice-recapitulated sequence of events, which begins each time with Crosby’s decision to set out on his cat food quest. With each subsequent retelling, this basic story is radically altered by chance and circumstance. The stakes of play are ratcheted up: Crosby’s tussle with Ivy ends in death (the most bleak and “existential” of the three scenarios); whales and sharks patrol the turbid waters; bloody vengeance is exacted for an accident; the rich and morally corrupt cannibalize a living whale as the East Side burns (ecological and social lessons are drawn); transgressive desire becomes a weapon; art passes away; two might-be lovers are [re]united at a party marking the End of Civilization. A final ray of light is teased: “I’m Crosby. I think we can change this story.” (p.101)

Page 14 from POST YORK

In terms of style and thematic structure, the book presents some interesting contrasts. Romberger’s visual style is a brutal, slashing black-and-white, stripped down and intensely powerful, but also able to catch fine physical nuances: Crosby’s incredulity or his determination, Ivy’s pouting beauty. The visual structure is also cinematic and the transitions frame to frame are dynamic and fluid. Much of the narration proceeds without dialog and we are left to imagine a rich extra-vocal soundscape. And the novel reflects on its own status as art with reference both to cinema and Renaissance fresco (pp. 46–47; 69; 84–87: a beautifully drawn-out argument). The politics are radical, eventually holding up a mirror to an elite culture in a state of utter moral and existential collapse. But there is room for love, and the relationship between Crosby and Ivy may be touched by Grace. At least, it’s a possibility.

NOTE: In addition to the novel proper, there is also (among other additional material from James and Crosby) an illustrated history of the project, and a set of annotated endnotes that will help the interested reader orient herself with respect to the scientific and public policy material consulted by the author.