The dolls we grew up playing with weren’t just dolls—they were alter egos, surrogate friends and family, and sometimes even symbolic forces of the universe. In this beautifully designed book, Betye Saar: Black Doll Blues, we get a chance to look at Saar’s special relationship to dolls: through photographs of her extensive doll collection, sketches and watercolors she has made of her dolls, and the assemblage work she has made over the years that incorporated dolls or parts thereof.

The book begins with an informative intro by Julie Roberts, co-founder and co-director of Roberts Projects, who tells us that when Saar decided to place her archives at the Getty Research Institute, they started sorting through her studio archives and found sketchbooks the artist has kept since the 1960s. The gallery has long represented Saar, so Roberts writes with natural familiarity and depth of knowledge.

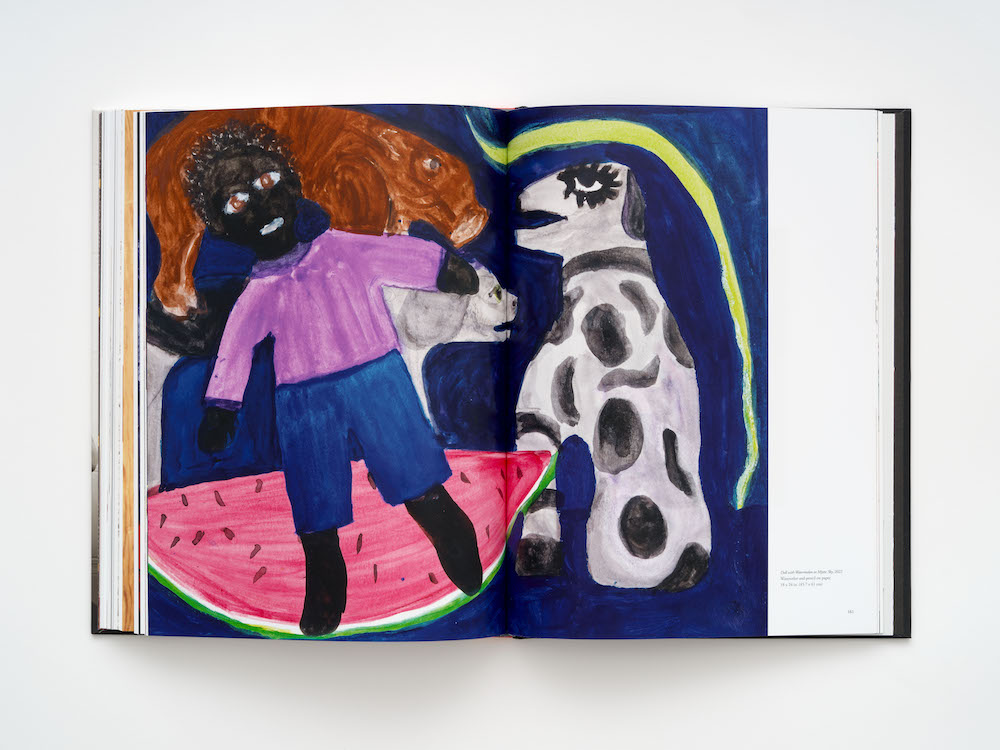

The first chapter is called “Sketchbooks” and shows drawings and watercolors of the Black dolls Saar has been collecting for decades. “While some may view these dolls as derogatory, and I agree some of them are,” Saar says in the book, “I didn’t create these paintings in the same spirit of ‘empowering Aunt Jemima.’ These paintings purely depict the Black dolls as they are, with the purpose of providing love and comfort to their owner.”

Betye Saar: Black Doll Blues, 2022. Published by Roberts Projects, Los Angeles.

During COVID Saar filled up several sketchbooks, and some of the artwork is paired with the actual doll she used as model. Yes, she does modify, and she often manages to give the drawn figures a liveliness of expression the physical dolls lack. For example, a late-19th-century cloth doll with a striped red dress becomes a rather energetic Black Floating Doll in Mystic Sky in 2022. Saar’s watercolor has the figure at a diagonal on the paper, her lips wearing a smile and her body floating against a dark blue sky filled with yellow stars, crescent moons and a ringed planet. She has escaped Earth, she is in the cosmos! That background touches on Saar’s longtime fascination for the mystical—the notebooks also include sketches of a hand with an eye in the palm, the sun radiating energy and light to the earth and moon, and a rainbow that arcs across two pages of a spiral notebook.

There’s even the story about how she found the Aunt Jemima doll that became her famous assemblage piece, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). Saar bought her at a swap meet: “She is a plastic kitchen accessory that had a notepad on the front of her skirt,” she says. “The broom handle is a pencil and on her left side I mirrored it with a plastic toy rifle.”

Some art books seem rather patched together, their material and chapters grouped randomly, but this one holds together from beginning to end, both in text and in pictures. Having seen some of these sketchbooks at Saar’s recent LACMA exhibition, I found the reproductions to be excellent, with strong colors and sharp details. Of course, much of this unity is due to Saar’s vision, which has been remarkably consistent since she started making art in the 1960s. Now in her 90s, she has produced a body of work that has forced us to re-examine the depiction of the Black figure in visual culture, and also to recognize personal spirituality rooted in folk traditions.