In Malian-American artist Penda Diakité’s transformational paintings and collages, every element is much more than what it seems. From her impossibly detail-rich photocollage to her unique technique of hand-engraving surfaces—and the historical cosmology of her subject matter—Diakité’s vision is one of (re)discovery, delight and surprise. Her exhibition is simultaneously an intensely personal narrative of her own identity and of a broader cultural excavation, in which the truth behind that which has passed into legend is recentered.

“Mansa Musso (She is King)” is a revelatory pageant of the female figures who, though their names were often lost to patriarchal history, played central roles in what would become modern West Africa—specifically the Mali Empire. Though the love of mixing bright colors and intricate patterns is a hallmark of Malian visual culture, the figures and objects in Diakité’s compositions are more than the effect of their palette since they were organized from sourced photographs. Painstakingly built from gathered pieces of the world—humans, animals, botanicals, foods, crafts, adornments—Diakité’s work reflects how mythologies, folklores and histories are themselves constructed.

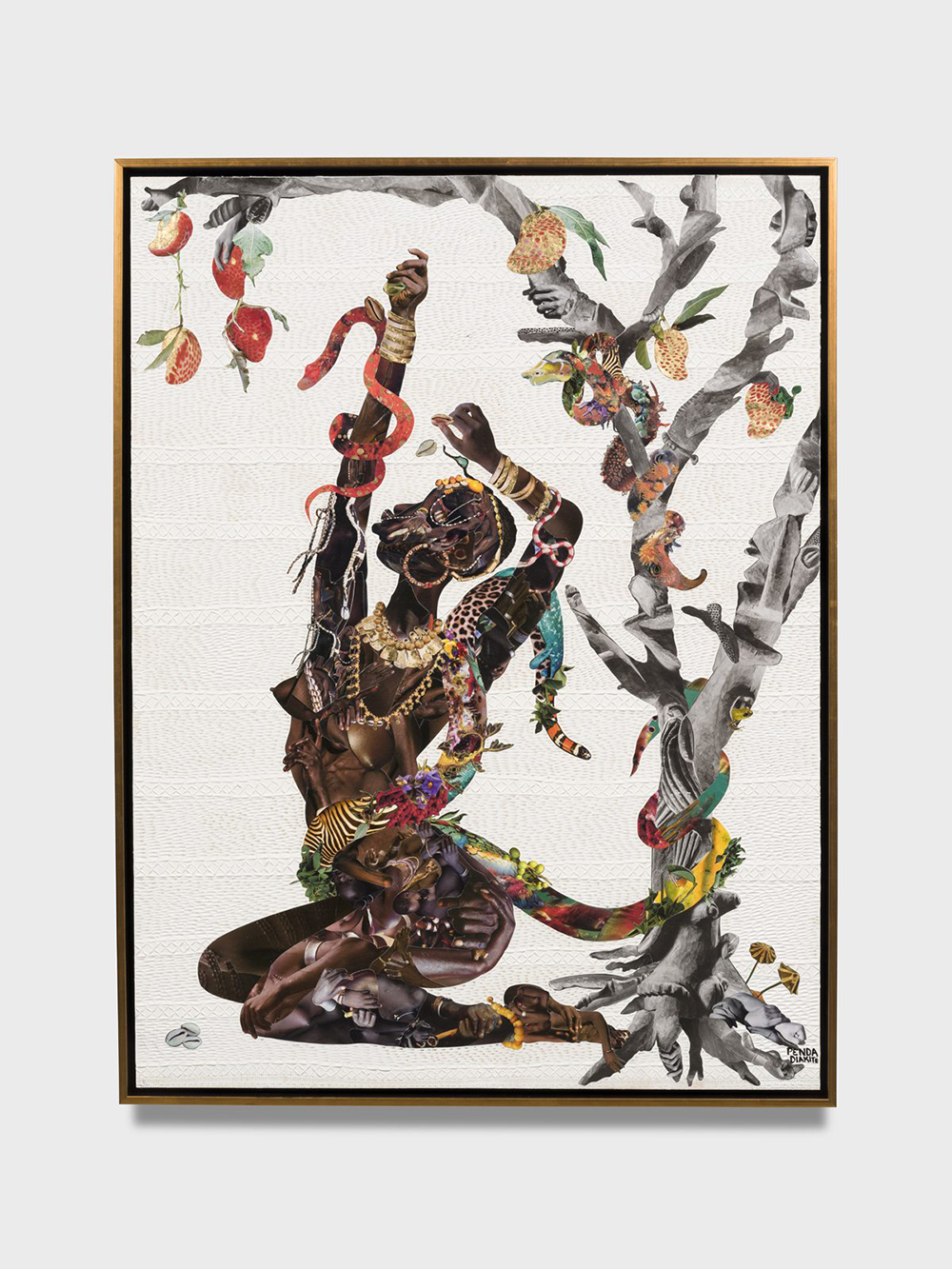

Penda Diakité, Sasuma Bereté, 2023

In hefty canvases displaying elaborate hand-cut collages of ambitious scale and unending detail, bodies (regal women of color dancing, praying, riding wild beasts) are created from images of limbs, especially hands; animals (lions, snakes, birds, buffalo, fish, camels) are formed from other species; and plants (flowers, trees, blossoms) are built out of humans and vivid creatures alike. For example, the roaring lion of Sogolon (2023) has a face made out of an upside-down blue parrot, a mane and tail from feathers and flowers, sharp claws from avian talons and a rider with a posture of motion and determination from the braceleted arms of countless others. In her specific approach to collage, Diakité uses the technique itself to create both illusion and story. Her deployment of source imagery blends line, shape, color, pattern and texture to brilliantly realize her clear and detailed figures. At the same time, those choices are not only optical—they encourage discovery and empathetic understanding in the viewer through specific poetic associations.

In the ebullient Shea Musso and Musso Koro Ba (2023), two female figures engage over ceremonial water vessels to enact what reads like a cleansing ritual. In MeeAn and the Serpent (2023), the snake that encircles her expresses not as a threat but as a living garland of thousands of flowers, embodying an ideal of beauty and power. Throughout the exhibition, the works are exceptionally prismatic and figuratively clear, but approached a few steps closer, each image reveals its universe of secrets embedded by the intensive labor and devotion of Diakité’s process. The effect is not only like magic: It contains a powerful demonstration of the interconnectedness of all things and highlights the infusion of meaningful symbolism into the blessed panoply of the world around us—and the women who have always looked after it.