It’s one thing to engage in a discourse about the influence of art historical movements on contemporary painters, and another still to analyze a particular artist’s specific set of influences, such as Nicole Eisenman’s robust relationship with the European Impressionists at the advance of the 20th century. But leave it to an art museum in Arles to organize an extensive embodiment of this discourse in the flesh. “Nicole Eisenman and the Moderns: Heads, Kisses, Battles” was organized in close collaboration with the artist—a salient fact which renders its premises all the more solid; no expert conjecture here, this is basically an externalization of Eisenman’s psychological roll call.

As one moves through the museological and, occasionally, more domestically styled interiors of the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, vignettes composed of several Eisenman works punctuate a flow in which other examples sit cheek by jowl with the 70 impressive works on loan from the Aargauer Kunsthaus in Switzerland, the Kunsthalle Bielefeld in Germany, the Kunstmuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands, and the collection of the Fondation Vincent van Gogh itself — including Pablo Picasso, James Ensor, Käthe Kollwitz, Edvard Munch, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Emil Nolde, and of course, Vincent van Gogh.

Vincent van Gogh, Poppy Field, 1890.

From within thoughtfully arrayed thematic assortments such as portraiture (self-portraits by men and nude portraits of women, largely), landscapes and villages, the bathers idiom, group fights and other urban social scenes, and a shared love of masks as a narrative and symbolic element, the shape of Eisenman’s attention toward art historical forebears emerges as not only informational but factual. She does far more than borrow—although borrow she does—she contextualizes personal observations on latter day modern life with those forebears’ observations on modernity’s onset. The mixture of optimism and dread on the canvases of the artists in this lineage is once again familiar to contemporary audiences, who from our far side of the 20th century can evaluate how their hopes and fears turned out.

Paul Camensich, Das Brautpaar (Oblomow and Oljga) [The Bride and Groom (Oblomov and Olyga)], 1928.

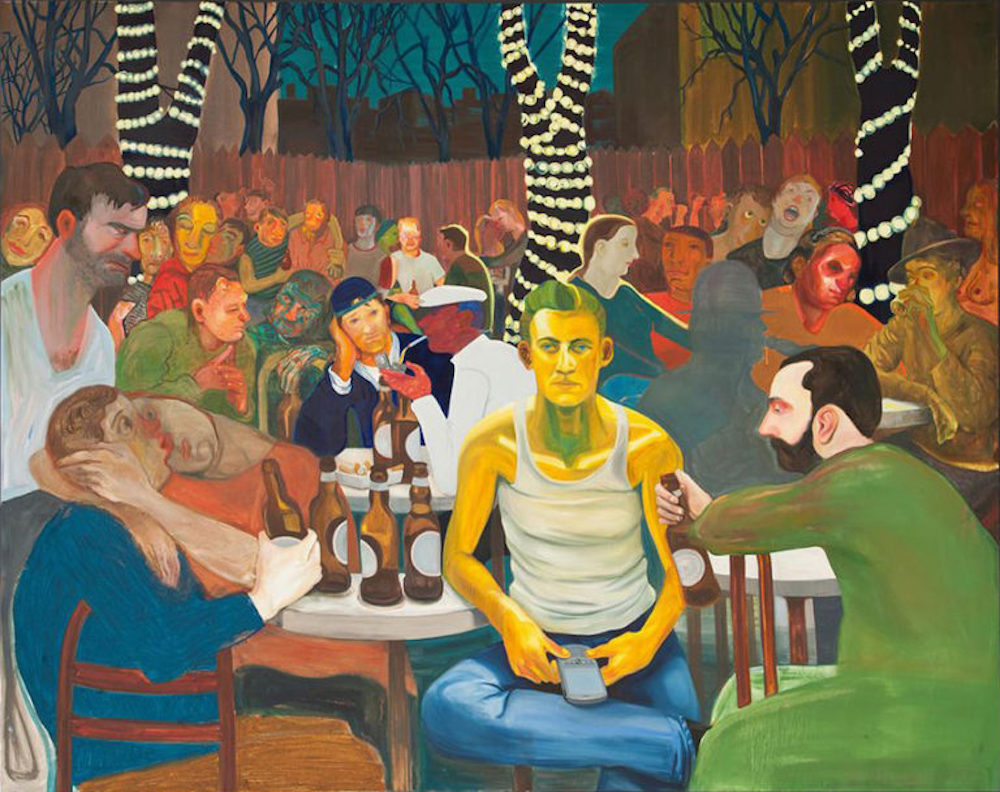

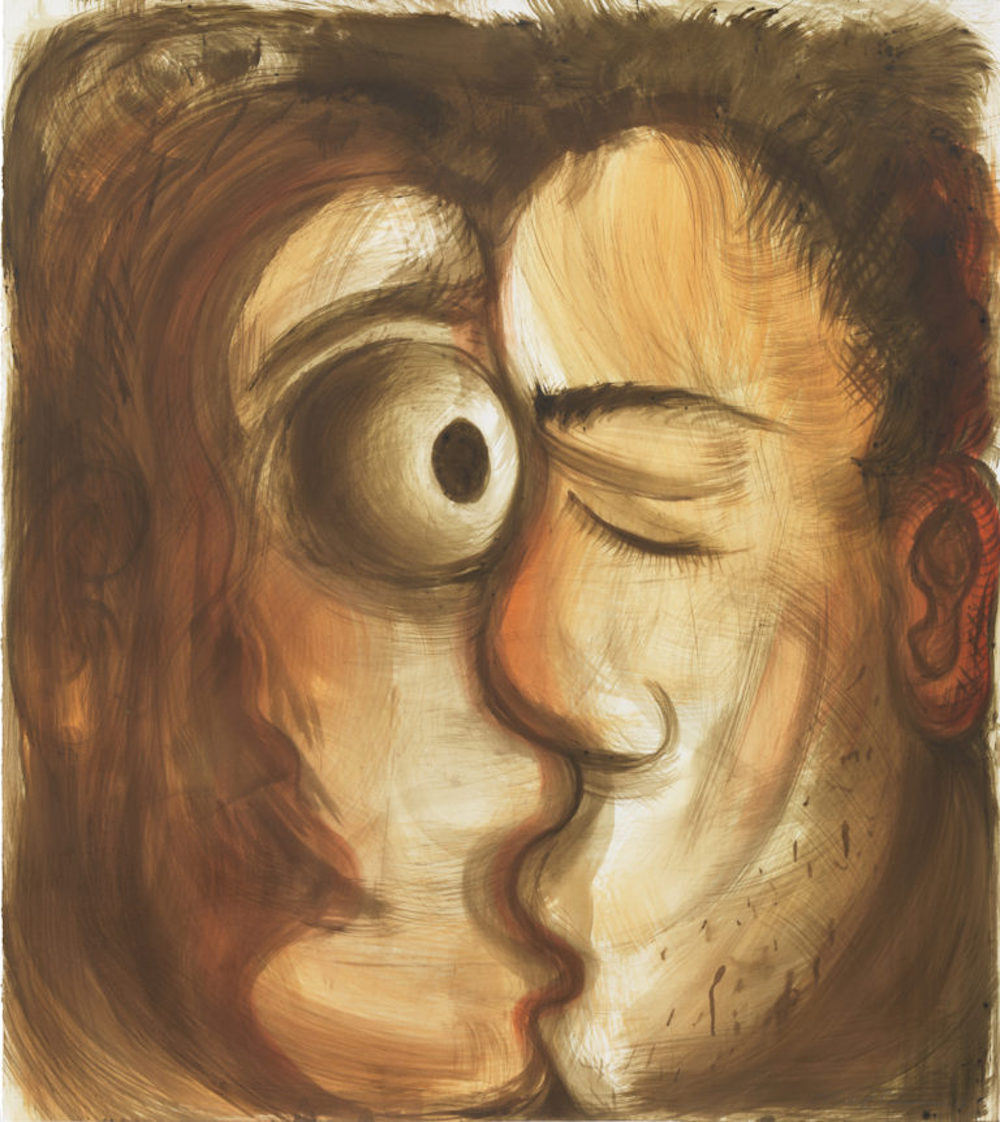

Of all Eisenman’s paintings included, the cornerstone works Brooklyn Biergarten II (2008) and Beer Garden with Ash/AK (2009) use some of the most direct art historical citations as their animating device; their relation to Renoir’s seminal “Dance at the Moulin de la Galette” from 1876 is overt and assertive, the better to set off the specifics of Eisenman’s updates, and to remind us if how much has, and has not, changed. The ink on paper work, Le Kiss Deux (2015), does much the same with regard to the famous work by Picasso which it channels, a meditation on line and intimacy that is equal parts visual pun and, in Eisenman’s hands, a frank question about the power dynamics at play in modern romance.

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden with Ash/AK, 2009.

Again and again across the show (whose gorgeous catalog is very much worth acquiring) we see examples of how Eisenman picks up on what the Impressionists and post-Impressionists started — a questioning of the order of things in light of the arrival of new ways of thinking and seeing, and of the changing nature of the individual’s concept of identity and their role in society. The exceptionally wonderful, beguiling, unsettling, empathetic masterpiece Night Studio (2009) might claim the most clarity in its assertions of the beauty of life in a gender-fluid bohemian odalisque utopia of German beer, American cigarettes, stacks of art books (read their spines for clues), atelier futons, work lights, costume hats with modern painting pedigrees, naked skin and woven textile rendered as shaped passages of pure abstraction, all set against a starry expanse prefiguring AbEx, under which two women reinvent themselves to their hearts content.

What a fabulous contextualizing and juxtaposition of Nicole Eisenman’s paintings, illuminated against the impressionist palette.