When Donovan Johnson and his new partnership cohort stepped in to renovate and relaunch the once-venerable Bill Lowe Gallery—transforming it into the buzzy and ambitious Johnson Lowe Gallery of today—it signaled more than a changing of the guard at one of Atlanta’s high-profile art spaces. It was emblematic of a sea change in the national and international aspirations of the whole city’s art ecosystem. Of course, art in Atlanta is not new; it’s been a cultural capital in music, sports, tech, film and television, food, and fashion, and there have been some exceptional galleries in business forever. But there has been a more recent, specific push to up the visual art game, as evidenced by both the arrival of UTA Artist Space to town and the recently held absolutely blockbuster second edition of Atlanta Art Week—a destination affair activating galleries, institutions, pop-ups, and studios across the city in the model of the Gallery Weekend programs familiar to New York, Los Angeles, Berlin, Miami and etc. But, unlike others, Atlanta’s version achieved a more intentional buy-in from the city’s many and glorious public collections and university museums (such as the High Museum and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art), as well as its several artist studio complexes like Murphy Rail Studios, Temporary Studios, Day & Night Projects and at Atlanta Contemporary..

Certainly, with the art world coming to town, the good people of Johnson Lowe Gallery were committed to bringing out something special for the occasion—something that showcased the most exciting and progressive art being made in Atlanta today, not only for the benefit of visiting audiences but more profoundly, emotionally even, for the audiences right there at home. “In Unity as in Division” is a group exhibition (seven simultaneous solo exhibitions really) featuring new works from artists working and living within the Atlanta Metropolitan Area—Demetri Burke, Danielle Deadwyler, Leia Genis, Wihro Kim, Masela Nkolo, Sergio Suarez, and Ellex Swavoni—each with a radically different approach to medium, style, and conceptual foundation, but all of whom share a deep engagement with the contested history and conditional potential of the body at the edge of tomorrow. As Atlanta knows a thing or two about how the past and future collide, the impressive curatorial effort yielded not only a satisfying exhibition in itself, but the sense of a real snapshot of the city’s artistic moment.

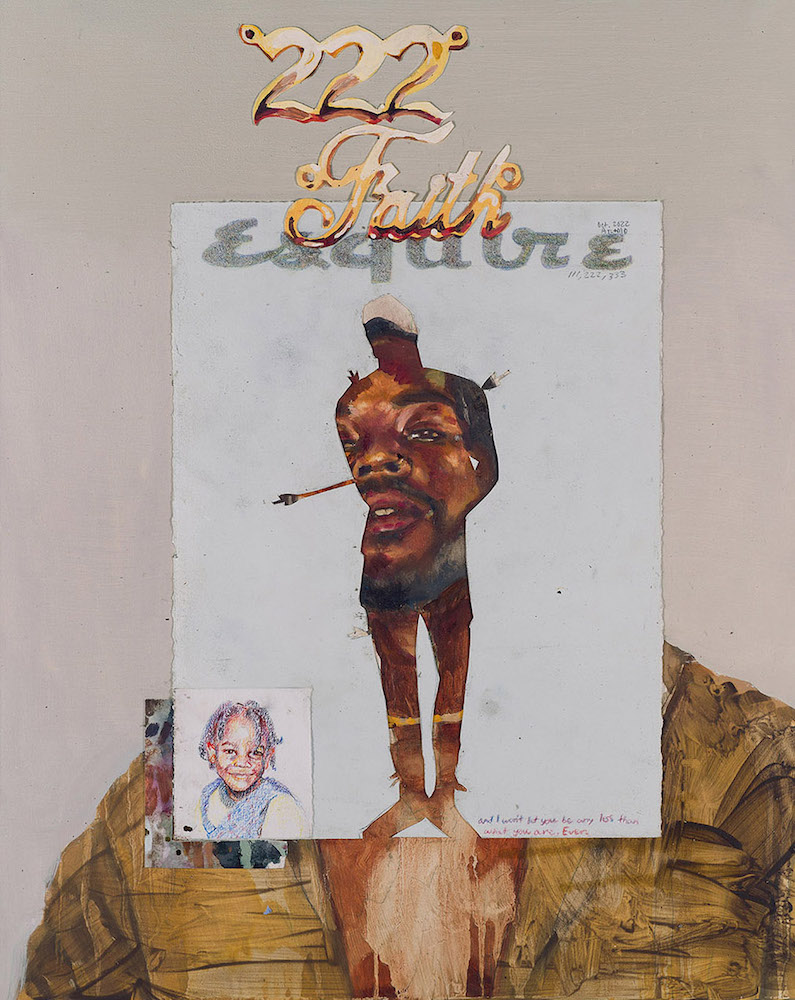

Demetri Burke, A Perfect Man, 2022.

With Demetri Burke’s heartfelt interventions in poetic portraiture; painter Wihro Kim’s Pop-inflected and paradoxical cognitive experiments; Danielle Deadwyler’s video art in which the Black femme body is both the site and subject, the actor and the acted upon, the gazed at and the unreachable; and Leia Genis’ photo- and textile-based gestural atmospheric unfurling of figures, existence, pattern, and vanishing, one felt that currents visible on contemporary art around the country and the world were very much manifesting within the specifics of Atlanta’s time and place. Grounded in both universal and personal lived experience but filtered through each artist’s individual culture framework and their material and optical passions, their diversity of experiences and confluence of creative paths was powerful to behold in this conversational juxtaposition.

Sergio Suarez pursues a multiplicitous dialectic in large monoprints, with paintings’ scale and object presence and the intimate mark-making of drawings. Like Blake meeting Posada, the work is simultaneously in dialogue with classic forms of Mexican printmaking, European metaphysical philosophy, Indigenous spiritual traditions, and the socio-political forces that shape history and identity in every context. By placing earthly elements of rock, stone, sand and talismanic sculptural objects in shallow prosceniums framing the works, they both enter the physical space of the viewer and set a ceremonial, theatrical tone for how to read them. His monochromatic but skillful and expressive scenarios have a way of collapsing several timelines and planar dimensions into single tableaux—the better to layer myth, art history, and modernity.

Ellex Swavoni gazes at the ancestral past while simultaneously imagining the future—or several possible futures. The language around the work is on the need for an essential, Black, feminine concept of creativity that considers the accumulated wisdom of ancestors, matriarchs, literature, design, music, science, and Pop culture, especially comics. This is especially fascinating because Swavoni’s slick, sexy, space-age abstractions with pierced picture planes, holding their taut and gentle sine curve surfaces to the light just so, suffused with pigment and surface and slashes that create spaceship-like curves—they look more like high-style science fiction or neurological models, in conversation with hard-edge abstractionists and architects like Zaha Hadid, than they do like ancestral portals. Or do they?

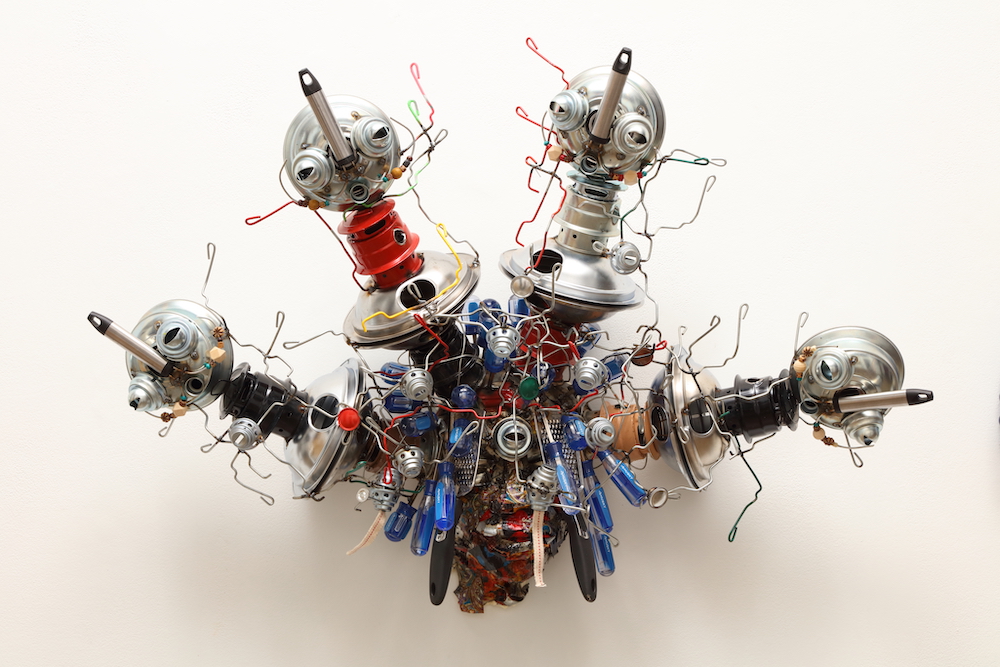

Masela Nkolo.

The striking, inventive, and poignant mixed media majesty of Masela Nkolo’s mask-motif wall sculptures arrive in this aesthetic, physical, and emotional context like a kaleidoscope in the shape of a life’s story—several simultaneous life stories, actually. Based in vernacular necessity-born crafting practices, referencing a practice from his Congolese childhood that merged scarcity of conventional art-making materials and a genuine joy in transforming discarded materials into things of power and beauty. Empty tins, rusted frames, carpentry tools, wire and plastic and bottle caps and springs; lanterns and wheels, ropes and tiles, and amassed collections of colorful, textural, shapely, and surreal bits and pieces—from these raw materials Nkolo weaves masks, headdresses, full figures, and abstract studies that present themselves with the whimsy of carnival and the gravitas of ritual. In Nkolo’s alchemy, past and present, Africa and America, high and low, delight and elegy come together into unforgettable entirety.

In an affecting West Coast connection, photography-forward gallery Jackson Fine Art opened Meghann Riepenhoff and Richard Misrach in a beguiling two-person exhibition entitled “Duet.” Misrach’s iconic work documents the elemental qualities and finds the plain spoken poetry in the deserts of the American West at the liminal places where civilization has intruded; he was Riepenhoff’s mentor during a time when she had left her native Atlanta to work in San Francisco. From him she picked up a spirit of adventure and a way of encountering the landscape (though at the moment at least, she prefers the tundra to the desert) at a deeper level than merely informational sight. While both photographers work differently in almost every possible way from style to material, their juxtaposition reads like the ongoing conversation that it is—one that’s just as much about photographic history, emotional presence, material adventurism, and a love of evocative sweeps and curious detail as it is about the landscape they both honor. Duets is on view through December 22.

And finally, not on the official agenda but popping up right in the middle of a particularly bustling weekend neighborhood, we were blessed to come across a compelling, eclectic group exhibition and music night organized by The Obsidian Collektive, producers of peripatetic pop-ups celebrating artists of color from across the region—and who in a fine full-circle coincidence of synchronicity, and even of unity in division, were also featuring among the work of dozens of talented Atlanta artists, several incredible wall-based abstractions and standing sculptures by Johnson Lowe Gallery artist Masela Nkolo, in a wide-ranging, spirited, and inviting group exhibition meditating further on abstraction and selfhood.

Thank you, Atlanta! We’re already looking forward to next year. And we heard a rumor you’re getting a new art fair in 2024! Stay up to date at atlantaartweek.co.