Agnes Martin, the great Abstract Expressionist painter (1912–2004), believed in cosmic connection. She labored over her famous grid paintings almost her entire professional life, except for a difficult break from 1968 until the early 1970s, and in them she strove to show her supernal sense of coherence. That is, she believed in “the perfection underlying life,” as she told Artforum’s Lizzie Borden in 1973. Does it matter that she had, in 1967, been treated for schizophrenia in New York’s Bellevue hospital, and received over 100 electroshock therapy treatments? Does it matter, also, that she stopped painting after this treatment for those five years? Or that she had been lovers with artists Lenore Tawney and Chryssa in the 1960s?

It does. In the Martin retrospective first installed by London’s Tate Modern, and now showing at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, we can see the full expression of Martin’s philosophy of spiritual communion. But while the LACMA show acknowledges her abandonment of painting from 1967 to around 1972, and also discloses her interest in Buddhism, its curators delete all information about Martin’s affections and endurances, and the mental illness that threatened to split her off forever from her art.

Born in Canada, and trained as a teacher, Martin began her career in Taos delineating organic forms, as in Untitled (1953), a black, white, blue and beige abstract of curved shapes. She later moved to New York and invented her totemic grids. These are large square works, first accomplished in the 1950s until 1967 in browns, grays and occasional blues. Besides their colors, the grids’ signal features are their composition: Martin penciled intricate lattices onto the canvases, and graced these matrices with delicately hued veils. LACMA presents these ’50s and ’60s paintings in rooms devoted to her pre-“break” work, and in them we can see her developing her vision of universal union.

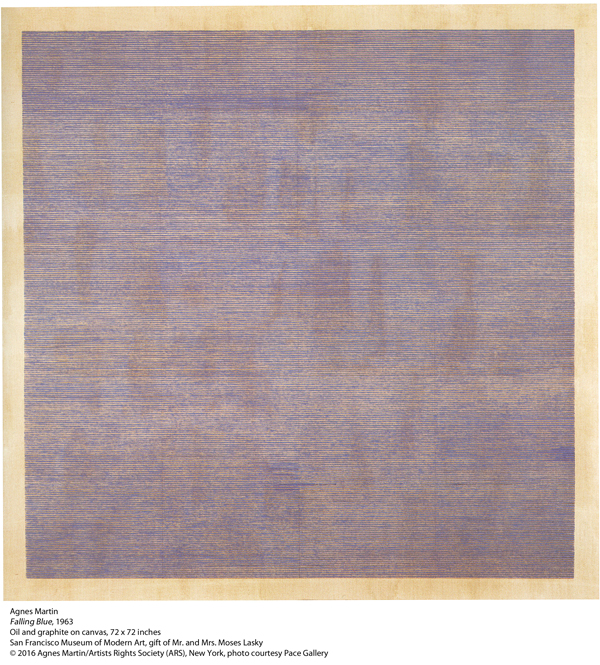

In Falling Blue (1963), Martin covers a large (71 ¾ x 72 inch) brown canvas with thin indigo lines. She follows Falling with 1964’s White Stone, a huge pale gray oil touched all over with small penciled squares. And then, in 1967’s marvelous Grass, she develops a finer mesh, and in each tiny box she dabs two colors of light green. All of these paintings look like sisters. Seen altogether, we can sense Martin describing the merging ley lines that gather the water, the sky, the stone and the grass. We can see her discovering the perfection that underlies all life.

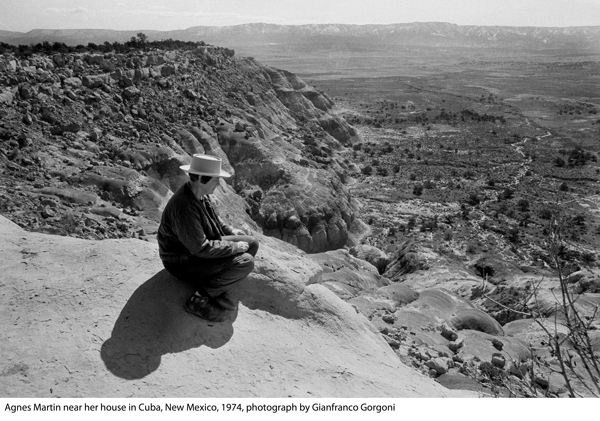

How hard was it for Martin to express these things? What price did she have to pay? During these years anti-sodomy laws remained constitutional and the American Psychiatric Association still categorized homosexuality as a mental illness (and would until 1973). And Martin suffered actual mental health problems, in the form of her schizophrenia: In 1967, she was discovered wandering Park Avenue in what has been described as a “psychotic episode” and thereafter submitted to ECT. Her escape from New York to the small town of Cuba, New Mexico, and her five-year pause followed.

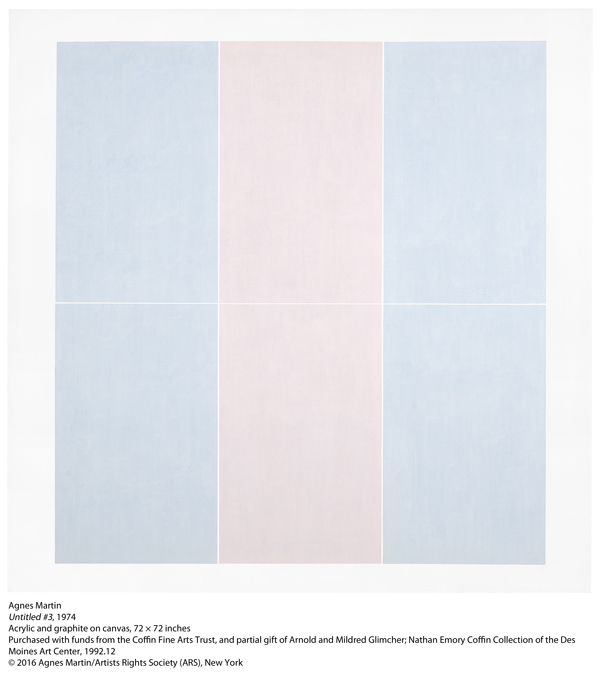

LACMA both refers to and closets these traumas by requiring patrons to walk through a hallway that connects the work pre- and post-break. On the hall’s wall, the curators offer text that alludes to Martin’s “artistic hiatus,” describing it as “meditative.” Once having traveled through Martin’s silent period, the visitor encounters a forest of huge, luminous, pink-blue works that recall the Southwestern sky but remain “Untitled.” Martin now embraced the ecstatic marriage of all existence, even that which cannot be named. Such is the case in 1974’s Untitled #3, which assembles deep blush and blue hues in an exhilarating astronomy made of six rectangles. Another wondrous work is the quartz-pink Untitled IX (1982), which envelops the viewer in glowing rose joy. Deeper into the retrospective, we see that Martin shifted her colors to somber grays in the 1990s, which LACMA deigns to assess as Martin’s acknowledgment of “the impending end.”

But what caused her breakthrough in 1974? Did her treatments liberate her, or almost crush her? Notably, Martin never wanted people to write about her personal life, and LACMA acquiesces. This is a mistake. First, it is unclear why Martin’s Buddhism, gender, aging and five-year escape from painting are considered appropriate subjects to uncover in the exhibition, but her sexuality and her mental agonies are not. More importantly, Martin’s vision of celestial and earthly harmony could be reduced to a dangerous platitude that “everything is beautiful.” It is important we understand that Martin saw life’s perfection even though she was marked as different, and suffered for it. Martin’s work is great in part because she saw an abstract, loving truth that was denied to her in concrete terms.

Failing to acknowledge Martin’s pain and oppression threatens to transform her art into an easy, untrue maxim of planetary sameness that she somehow turned from an existential threat into a vision of inclusivity and hope.

“Agnes Martin” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, through September 11, 2016.

0 Comments