For those familiar with the late painter Noah Davis and the lasting influence of his Underground Museum—the Arlington Heights exhibition space he operated with his wife and collaborator, Karon Davis—the Hammer Museum’s eponymously titled retrospective survey of the artist ten years after his untimely passing may shake up memories of life in a recent, but nearly forgotten, pre-pandemic Los Angeles.

Walking through the show, I found myself tarrying with a sticky web of difficult-to-unravel thoughts and feelings tied to Davis’s consistent engagement with Black quotidian life, especially the institution he tried to build, and which remains a seminal part of his legacy. Punctuating these feelings was the unavoidable theme of mortality: Davis created a number of the works after being diagnosed with liposarcoma, a rare form of soft tissue cancer, but the paintings he produced in his early career readily seem charged with a sense of prophetic dismay.

The first work that greets viewers at the entrance of the linearly organized exhibition, 40 Acres and a Unicorn (2007), holds out a skeleton key that unlocks two crucial concerns spread throughout Davis’ oeuvre: The representation of Black life as a site of soul-searching psychological interiority, and the political struggles that have left the creative and cultural contributions of Black people largely undervalued, ignored, or appropriated. While the painting’s self-descriptive title is an explicit reference to General William Tecumseh Sherman’s 1865 Special Field Orders No. 15, which famously granted land and livestock to some freed slaves in the aftermath of the Civil War, the image it bears of dark-skinned child riding a unicorn over a black abyss oozes with contradictory feelings—by turns wishful and optimistic and at others mournful and resigned—that perhaps emerge from a wished-for but impossible history.

Noah Davis, 40 Acres and a Unicorn, 2007. Private Collection, Courtesy David Zwirner. Photo: Anna Arca. Courtesy of the Estate of Noah Davis

and David Zwirner.

As a retrospective survey, “Noah Davis” shows an artist in the process of developing his painterly language. The exhibition offers several examples of Davis quoting his influences, including an entire room devoted to his parodic sculptural remakes of artists like Jeff Koons and Marcel Duchamp that Davis previously exhibited as “Imitation of Wealth” at the Underground Museum in 2013. While the survey’s curators provide a lengthy list of notable influences ranging from predecessors like Mark Rothko and Romare Bearden to local peers and contemporaries like Mark Bradford, there are surprising encounters throughout the exhibit that indicate the breadth of Davis’s engagement with painting as a language and history. For me, the most compelling of these unspoken influences is acclaimed British painter Francis Bacon, who, like Davis, described his painterly activity in terms of the immediate sensory experience of facture — how paint is used to create effects comparable to syntax, not just images, on a surface.

The dream-like, visceral distortions found in works like Bad Boy for Life (2007) and the series of untitled paintings Davis located at the end of the retrospective are most reminiscent of Bacon’s searing portraits of his friends and lovers. In Bad Boy for Life, where touches of Bacon’s style and influence are arguably most visible, Davis presents a Black maternal figure as his sitter. Mouthlessly gazing at the viewer, hand raised as if preparing to spank the boy in her lap, but showing no sign that she will complete the action, the woman is frozen at an ambivalent climax. Meanwhile, the child, wearing what appears to be a military uniform complete with matching boots, has an expressionless face. His lips, hewn into the open shape of a vowel, contrast the woman’s implicit silence with the impending but unclassifiable vocalization of the child, linking the two figures in a deadlock.

Completed near the end of Davis’ life when he began working out of his family’s garage in Ojai, California, the later untitled paintings appear deceptively simple. Showing isolated figures in mundane poses, these works rely on paint to eke out their story. In one, a standing figure appears caught in a balancing act that places his hands forward while his shadow shortens behind him. The thin layers of paint that define the figure’s shape and separate him from the rest of the canvas are dark near his feet, but eerily transparent near his torso. Hunched at the neck, as if someone had pinched and lifted him from the back of his shirt, his upper body seems to be fading into the wall behind him. In another, Davis paints a man lying chest up in an ambiguous setting with his hat placed beside him in his arms.

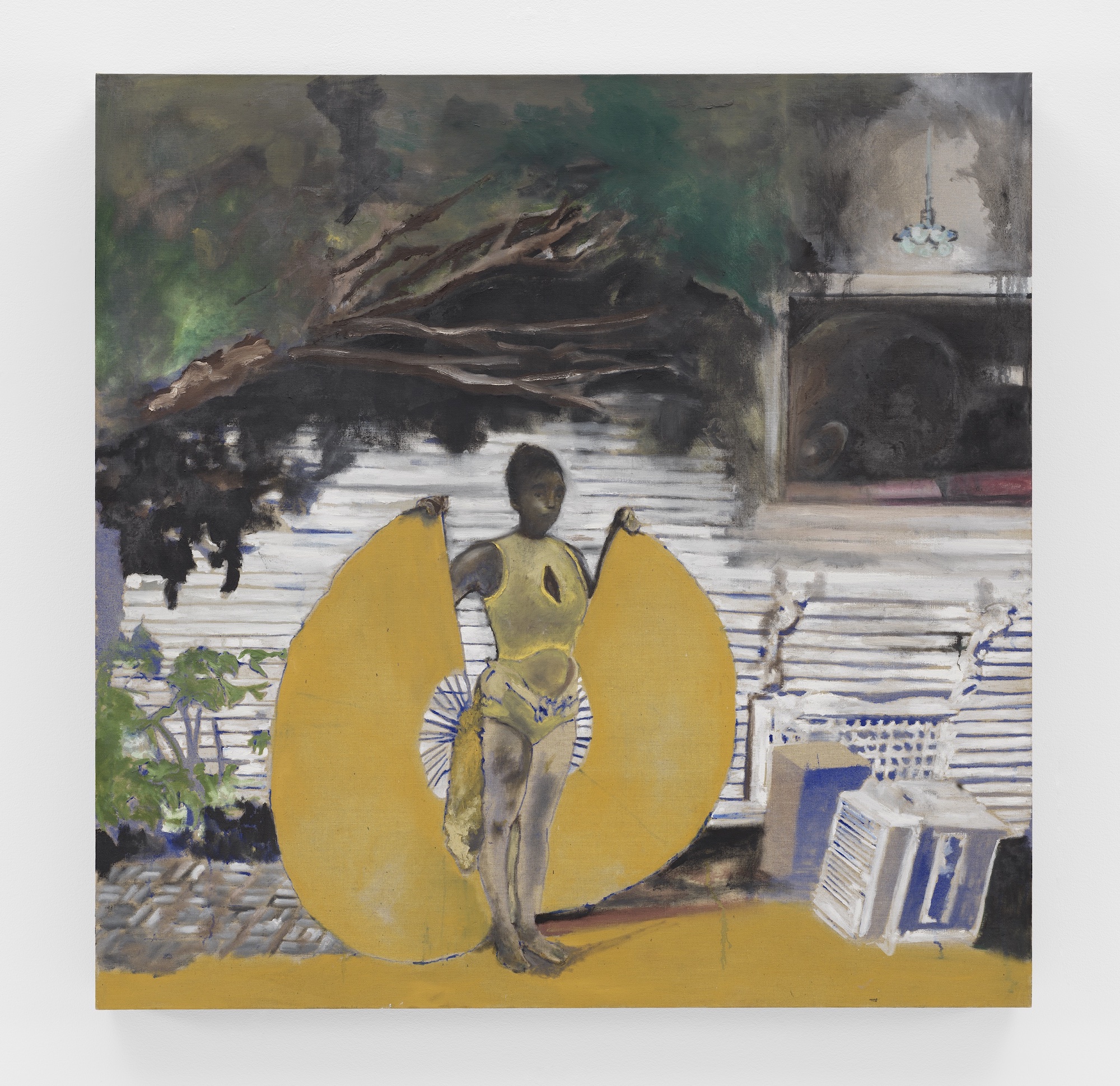

Noah Davis, Isis, 2009. Foundation Art Collection. Photo: Kerry McFate. Courtesy of the Estate of Noah Davis and David Zwirner

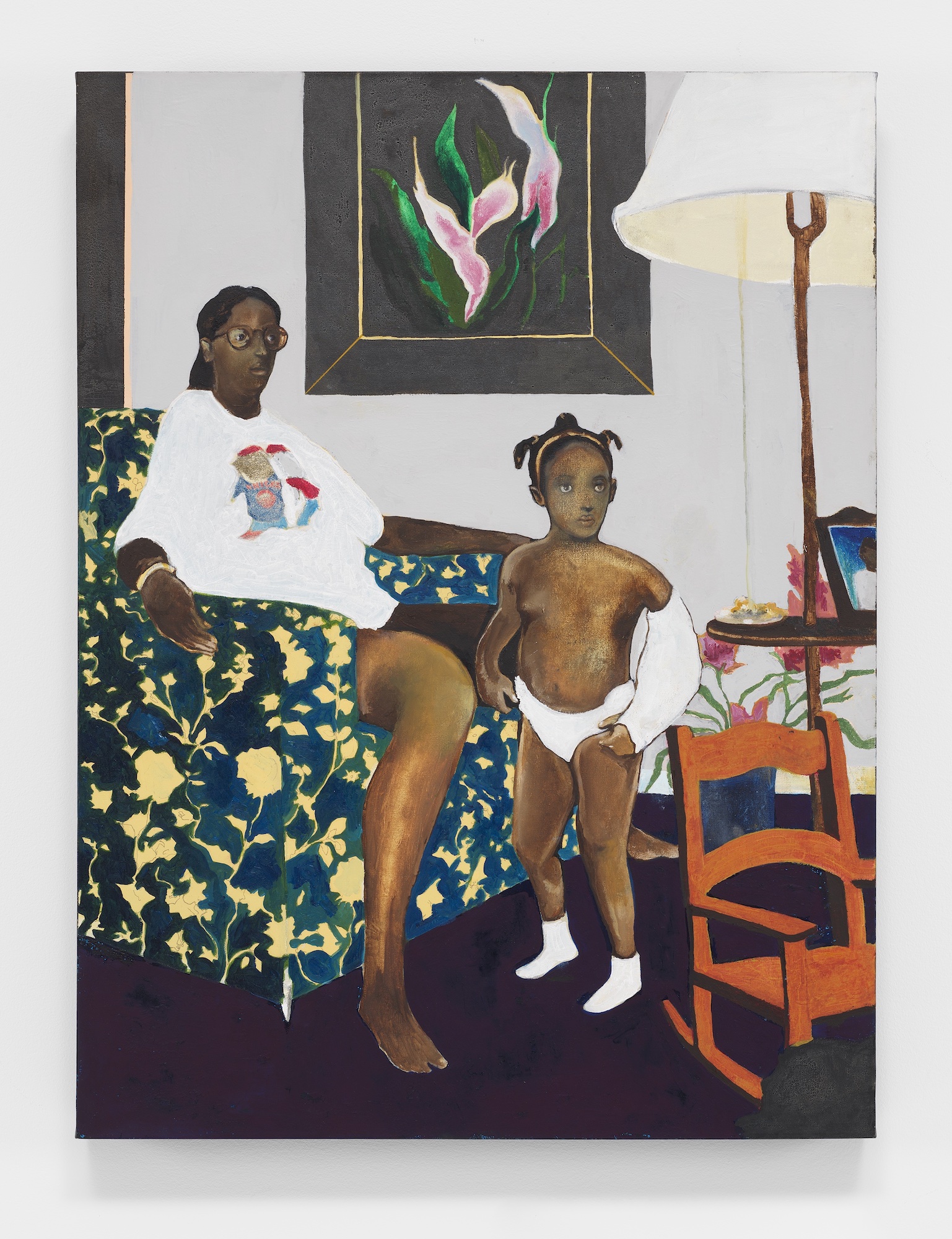

The middle corridors of the exhibition depart from this overt dream logic and instead take on individual focuses related to the series Davis produced at the time. “BESTPAINTERALIVE.COM” collects photographs, viewable in a vitrine alongside the paintings, that form the source material for Davis’s examinations of Black life found in works such as Single Mother with Father out of the Picture (2007–8) and Isis (2009). “GODS OF THE AFTERLIFE” includes paintings produced for Davis’s first solo exhibition at Tilton Gallery in New York in 2009. “The MISSING LINK,” produced the same year as the “Imitation of Wealth,” shows Davis filtering his examinations of Black life through influences like Édouard Manet and Piet Mondrian. “SEVENTY WORKS” gathers the works on paper Davis created during the six months in 2013 when he underwent chemotherapy. 1975 spans paintings Davis produced using archival family photographs from that year and which highlight his growing use of rabbit-skin glue and wooden frames. “PUERTO DEL RIO” contains both his paintings of the Los Angeles housing project and works from his Congo series that are based on photographs Davis’ brother, the artist Kahlil Joseph, took during a trip to Africa.

Weeks after first viewing the exhibition, I’m still haunted by the idea that we live in a world that is desperate to forget its history. But something about Davis’ many attempts to represent the world and our inability to see its magic soothes this feeling of collective amnesia. Clearly a virtuosic talent able to attract blue-chip representation and institutional support from venerated collecting bodies including the Rubell Museum and Mellon Foundation, Davis’ market success, which no doubt helped sustain interest in his work and created the opportunity to gather his work in a museum setting within a decade of his death, is also an unintended reminder of the resources necessary to preserve an artist’s legacy. In the aftermath of the pandemic, during the political turbulence of the second Trump administration, the exhibition presents a difficult-to-dismiss alternative world where a deeper sensitivity to the human condition might thrive. With Davis’ absence, that sensitivity grows stronger and illuminates his prophetic tendencies, encouraging us to grapple with the past while preparing for inevitable calamity in the future.