Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Wyatt Coday

-

RUBY ZARSKY

at CeradonGoddesses once etched into stone tablets and later deified in oil paintings now live another immortal existence: nude or scantily clad, wet and voluptuous, digitally rendered and plastered across Reddit or X, they resemble magical beasts or aliens. Some have had their hip and breast size transformed to impossible proportions while others have otherworldly skin and hair colors. In some cases, these goddesses possess multiple sets of genitals or pairs of dimorphic sexual organs—a gesture that humans have been exploring since an unknown sculptor created the Sleeping Hermaphrodite in Imperial Rome. The glow of the screen is new but the subject matter is not—portraits like these have been with us since the dawn of culture. I bring this up because with the current political hysteria about transgender rights flooding public discourse, it’s helpful to remember that humans have been horny freaks since time immemorial. To me, this suggests that our horniness and desire to emulate and even pleasure ourselves to the bodies we imagine is both healthy and natural.

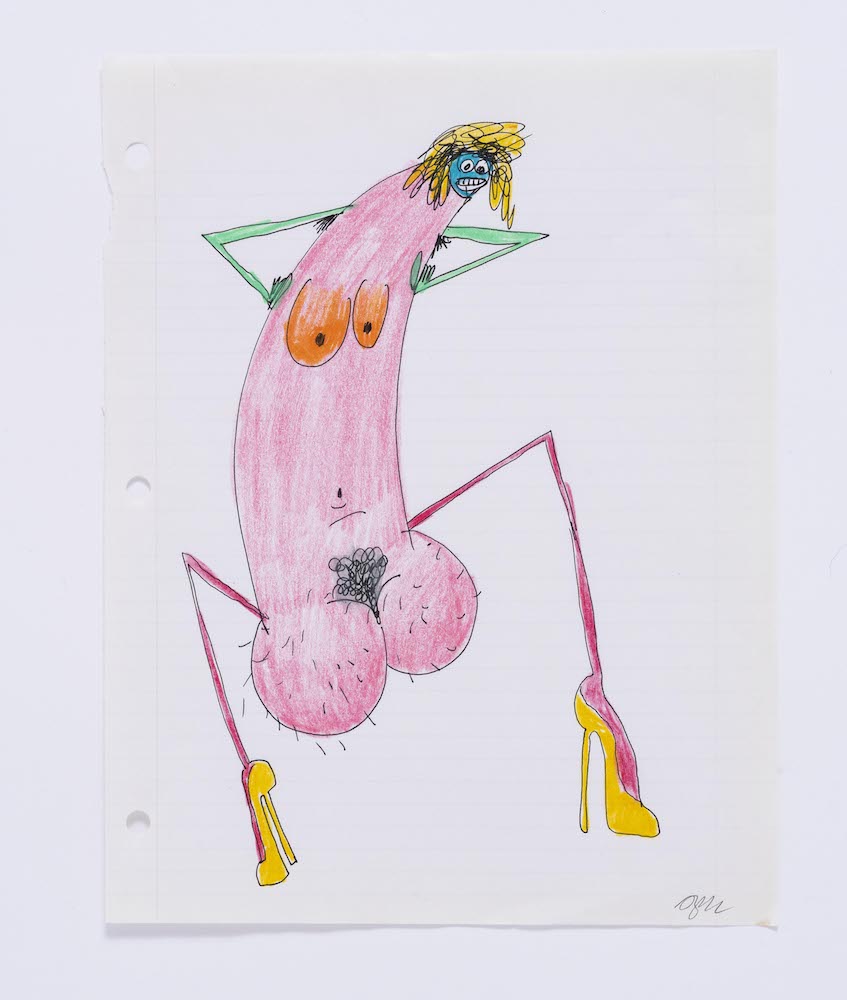

“RULE 34,” the debut solo exhibition of New York artist and former member of Sateen Ruby Zarsky at Ceradon Gallery, is a meditation on the serene pleasures such images can grant their viewers. The more than 30 works included in the show are replete with images of nude, possibly hermaphroditic women. Obscene by design and inflected with homages to popular anime and video-game characters, “RULE 34” abounds with girthy uncut penises and voluptuous breasts on unblemished, athletic goddesses.

In Cosmic Consciousness (2024), a be-dicked woman resembling Chun-Li Xiang, a character from the 1991 video game Street Fighter II, holds herself up from a seated position, spreading her legs to display a penis that is larger and longer than her foot. While it may be tempting to dismiss the painting as pornographic or fetishistic, such thinking ignores Zarsky’s subtle choices—especially the choice to use Chun-Li, the first playable female character in the Street Fighter series, as a subject—to produce the image.

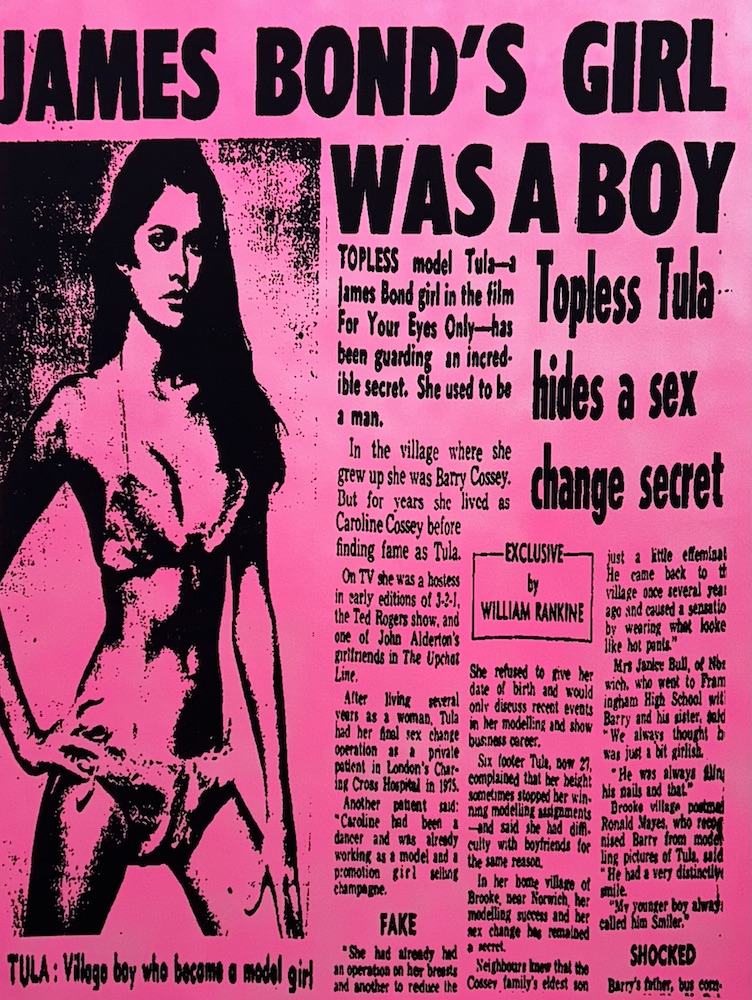

Ruby Zarsky, “Fierce Diva,” 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Ceradon Gallery. Among the other works, Fierce Diva (2024) and Glorious Queen (2024), a pair of paintings that feature scan-like renderings of early transvestigations that feature transsexual women fooling johns and making careers as athletes and celebrities, stand out as illustrative examples of Zarsky’s historical eye. Meanwhile, the impeccably titled To Kill a Chimera You Must Use Lead From Above (2024) seems to be the skeleton key that unlocks the entire exhibition, with the hung, latex-wearing dominatrix at its center fingering another t-girl and placing her hands around the circular, schematized grid that erupts from her ass.

Tucked within these references to recent digital and trans history is an implicit send-up of the places where queer people, and transwomen in particular, sourced their identities while seeking refuge from the imprisoning mythologies of cisgender heterosexuality. Artists like Zarsky, who embrace and honor the obscene, are able to accomplish a form of radical honesty and trust in their desires that many will never experience. In the most liberating sense possible, “RULE 34” lacks cowardice. The show is as political as it is pleasurable.

-

Race Place

Since 2018, I’ve made a point of catching the Made in L.A biennial at the Hammer Museum, and at times I’ve come away with mixed feelings toward the city’s most ambitious survey exhibition. While it is worth asking — as many critics before me have — whether or not a biennal is a worthwhile form for an exhibition, I won’t attempt to answer that question here. But even after taking into account the awkwardness of the curatorial premise, Made in L.A.’s most recent iteration, Acts of Living, left me particularly disappointed.

Organized by curators Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez with support from Ashton Cooper, the show’s curatorial thesis drew on large, abstract ideas — “community networks,” “queer affect,” and “indigenous and diasporic histories” — while its floor plan effectively placed artists into simplified cultural groupings, especially race-driven clusters. Far from serving its stated mission, this decision obscured the terms on which the show was constructed and instead repeated the sort of myths about art that cultural institutions like to tell themselves. Worse still, the exhibition overlooked disciplines and media—most notably video-based work—that have historically held a significant presence in Los Angeles.

Entering the museum earlier this year from its west-facing rear entrance and passing Dominique Moody’s trailer, N.O.M.A.D. (Narrative, Odyssey, Manifesting, Artistic, Dreams) (2015–2023) outside, I stopped in front of Roksana Pirouzmand’s fountain sculpture Until All Is Dissolved (2023) and then made my way to the main foyer where Devin Reynolds’ mural occupied the walls. While these works were impressive, arriving at Guadalupe Rosales’ installation on the museum’s first floor cemented a feeling of cognitive dissonance that I couldn’t shake as I made my way through the rest of the exhibition. Notably, the wall didactic describing Rosales’ work suggested that her use of “baroque, gilded materials of low-riding and custom car culture” was “unexpected.” But unexpected for whom? Many artists and exhibitions have made similar references to the city’s low-rider subculture, including the duo Postcommodity in their 2023 show at LAXART, Some Reach While Others Clap. How many times must art institutions rediscover cornerstones of Los Angeles’ Latinx culture, and to what end?

Jibz Cameron, Me, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist. On the second floor, artists were mostly clustered by their ethnic or racial backgrounds. The second-floor gallery that leads to Ishi Glinsky’s Inertia—Warn the Animals (2023), the room-sized mixed-media sculpture that depicts the masked figure from Wes Craven’s 1996 horror film Scream, primarily contains work from Indigenous artists Jackie Amézquita, Luis Bermudez, and Esteban Ramón Pérez. Instead of opening new and

unexpected connections among these artists, the decision to cluster them in accordance with their cultural background isolated their work and prevented deeper resonances from coming to the surface among the broader cast of included artists. Instead of forging or revealing unacknowledged currents between these artists, the exhibition tokenized their contributions and relied on empty intellectualization to do so. The room where queer artists Jibz Cameron, Pippa Garner, Page Person and Young Joon Kwak were presented in one corner likewise failed in that respect.Considering the show’s tokenizing curatorial approach, the verbosity of such claims in the exhibition literature as “opening up seemingly familiar things to allow for new interpretations” and “destabilizes fixed ideas of culture and gives voice” fall especially flat. Unfortunately, this kind of hollow and abstract International Art English tends to point towards a curatorial approach more concerned with lofty ideals than material critique or art-historical research. To put it bluntly, the didactics the museum circulated in its releases and displayed on the walls described a different, less compelling exhibition than what was on view. With Miller Robinson’s two-channel video Tackle box, water filter, clothing rack (2023) and its small LCD screen being the sole video on display, it also seems that the curatorial decision to focus on racial and ethnic identities and cluster already similar works may have led to other significant blind spots.

Without didactics or explicit language pointing toward its racialized curatorial strategy, Acts of Living left viewers to piece together why its corridors are dominated by identities assumed to be conjoined, not artworks in contrapuntal formations. To borrow a musical metaphor, the arrangement lacked a melodic theme that transformed the individual works into a substantive, memorable composition. In retrospect, if the works in Acts of

Living had been paired with a stronger argumentative current and language that established their shared culture, I would be more sympathetic. But it was difficult to view the exhibition’s reliance on race, culture and ethnography as intentional when works like Chiffon Thomas’s Untitled (2021), which sat alone and decontextualized in the exhibition’s final corridor, were displayed as if they had been forgotten about until installation day.

Akinsanya Kambon and Sula Bermúdez-Silverman. Installation view, Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 1-December 31, 2023. Photo: Charles White. What makes matters worse is how race seems to impact where artists fall in the exhibition’s sequencing. Aside from Reynolds’ mural in the main entrance and Moody’s trailer outside, Thomas, Sula Bermúdez-Silverman, Emmanuel Louisnord Desir, Akinsanya Kambon and Teresa Tolliver, all of the other Black artists included in the exhibition had their works relegated to the exhibition’s final chambers. While Thomas’ contribution sat abandoned near the second-floor gallery’s exit, sculpture by Bermúdez-Silverman, Kambon and Tolliver were grouped so closely together that it was sometimes difficult to discern which piece belonged to which artist, especially because their work responded to similar colonial histories and drew from such earthen materials as wood, clay and iron powder, giving them a shared rusted appearance.

There are many storied critiques of the survey exhibition. As a format, it promises a wide view. But with that width comes the risk of the survey losing depth and flattening its distinct pieces into a uniform slush. With Acts of Living, I worry that the exhibition became a means to signal relationships to ideas, while the artists and their artworks become fodder for a thesis that ultimately made no distinct claims.