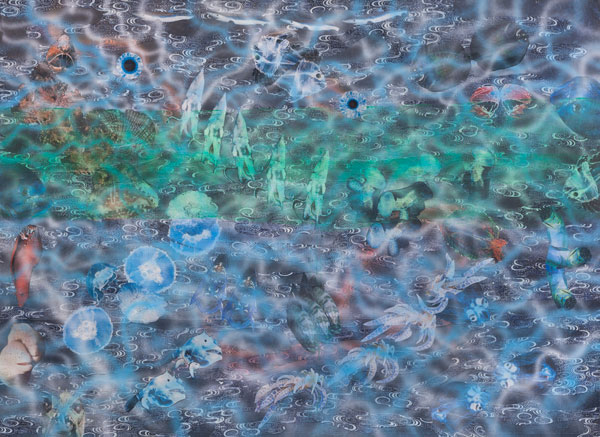

Ages-old art historical forces of the sublime and the picturesque battle it out across a suite of abstract landscapes, in about 20 fabulously chromatic, profoundly emotional, large-scale textile-based mixed media works by Merion Estes. Picturesque, because her take on the landscape idiom is infused with modes of beauty and compositional structures full of movement, rich detail and pleasing proportions. Sublime, because closer contemplation reveals increasingly dire, even sinister forces at work, threatening our environment with the terrors of darkness and degradation. These exotic fables and cautionary tales plead their case in the language of maximum allure; the danger comes later.

Estes’ Cassandra-like voice does sound its warnings in the titles—including an oceanic piece actually called Cautionary Tale (2015). Landscape-derived and somehow both ironic and literal, the titles are like clouds forming across the proverbial sunniness of the images, which prompts the viewer to render attention to details of disruption, fetidness, entropy, litter and death that punctuate the prismatic sweeps. Black Star (2016) is a bright constellation of golden Impressionist batik. Full of fissures and cracks in its firmament, it is glorious and mournful, fractal and vertiginous. Radioactive Sea (2017) and Desolation Row (2013) highlight a primitivist aspect in her rendered figures that goes to a slightly ancient, pagan place. Chemical Falls (2016) and High Noon (2016) demonstrate Asian and Indian influences not only in their verticality but in the scroll-like waterfall centrality of their motifs. Among the most literal in pictorial terms are the charming Melancholia (2012) with its folksy Hudson River School triangles of cultivated hillsides, and the explosive Yellow River (2015) with the solid glitter snaking through the earth below a fiery lava sky.

It’s tempting to think of the works as paintings, because of their scale, gestural expression, array of texture, proliferation of detail and power-packed palette. However not only for accuracy but also because the choices of material and technique are themselves carriers of the artist’s meaning, it is crucial to realize they are primarily found-fabric collage, with additional elements of acrylic, photo transfer, and occasionally spray paint and glitter.

The salient role of photo-transfer is to operate as an element of both drawing and of that which we expect from the collage genre’s material aesthetic—whereas in fact what her collages are built of is not photographs but an expansive archive of unique textiles from around the globe. On one hand, these fabrics are found objects and constitute borrowed images; but in their own schematic representations of natural imagery, the textiles themselves get to an intersectional and allegorical place close to where Estes was already going—a place where Bauhaus, Pattern & Decoration, and multiculturalist perspectives converge on a bucolic political edge. Estes combines an elevated appreciation for textiles’ visual impact and material worth with a fervent embrace of strategies for beauty, and a knack for the introduction of sirens into the symphony.