Mark Steven Greenfield has been something of a fixture on the Los Angeles art scene since the 1970s, better known as an administrator and arts advocate than as an artist. Greenfield has not bowed out of high-profile art-related activity altogether, but he is now able to define himself by his own artwork. And, being able to clarify such an identity, Greenfield reveals himself as a didact and a political voice—but never a pedant or mere polemicist.

Including vitrines and videos containing the artist’s widely varied sources, Greenfield’s retrospective touches on all aspects and periods of his work with an admirable economy. Indeed, without being parsimonious (it contains over 100 artworks), the selection leaves one wanting to see more from several of his periods, older and newer, precisely because they are explained and sampled so clearly. This approach honors the artist’s own precision and inventiveness. Trained as a graphic artist, Greenfield himself has always relied on visual clarity and focus on the image. Even when experimenting with all-over abstraction, as he did in the mid-1970s, he harnessed that experimentation to representation, turning his nebulous forms into stars, galaxies and other astronomical images—interlarded with references to things going on very much “on the ground.”

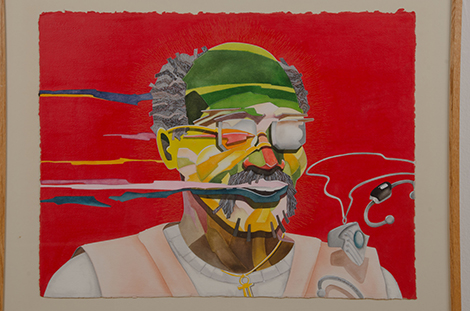

This graphic lucidity serves Greenfield as well now as it did a third of a century ago; and, indeed, its formal relationships haven’t changed much. A pictorial field dense with marks—drippy lines, vibrating dots, writing-like ciphers, all manners of calligraphy gone random—serves now, as then, as the optical bed for a single, perhaps iconic figure. In his decades-old renditions of galaxies, Greenfield would often lay in a figure in black silhouette. In the paintings he’s done in the last couple of years, that same stark figure-ground relationship pertains. And it’s the same kind of figure—its meaning changed drastically even as its context stays the same.

That context is what has preoccupied Greenfield his whole career, even life. He has dedicated more or less his entire artistic output to the consideration of an enduring circumstance: the life, social and cultural, led and experienced by African Americans. He has referenced and built off the achievements of African American artists (such as musician Sun Ra), documented his own family’s varied history in a series of banners, looked at African customs and beliefs as they traveled the Middle Passage (and as they continue to flourish in Africa), portrayed various mentors and figures in the cultural life of African American Los Angeles, and so forth. Apparently, he never lets his mind or heart stray far from issues of racial expression and racial depiction.

In his earlier years Greenfield was concerned with putting forth a positive image of black America, and to this end the young artist was willing to seal himself in a rhetorical straitjacket; enthusiastic and vividly wrought as his homages to artists and street life are, they seem taken from others’ image banks. But by the 1980s Greenfield had found his own voice—not only his own style(s), but his own imagery and a more personalized involvement in his subject matter—and has honed his sense and mode of expression ever since.

Particularly in the last decade, Greenfield has harnessed his method and even technique to an overarching project, that of deconstructing—through a complex but easily read system of parodic appropriation—the image nonblacks have of African Americans in this country. Greenfield has intensely researched a history of visual degradation going back before the abolition of slavery, including such now-embarrassing subjects as minstrel shows and the depiction of African Americans in commercial animation; his recent work, especially gathered and concentrated here, constitutes an indignant cry against a persistent and pervasive flow of indignity.

For all the rage that boils out of such series as “Blackatcha”—where defiant declarations are arranged optometrist-chart-style against historical photographs normally showing black people in compromised positions, and “Animalicious,” which identifies and isolates the exaggerations of racial and class features that cartoonists were wont to employ as a kind of social shorthand, Greenfield re-presents the grotesqueries he has identified with broad humor. He is thus able to clarify these jigaboo caricatures and coarse anthropomorphizations as perversions that affront the black viewer and shame the white viewer through their very wit. He appreciates the potential artfulness of these depictions, and uses and amplifies that very elegance, jiu jitsu style, to critique and deflate their racist pretense. It’s more than a history lesson: it’s a lesson in remembering, regretting and redressing.