The Moon landing’s 50th anniversary can’t be avoided. Waxing at full, it feels like the last gasp. The defining moment for some in the baby boom generation, what does the Apollo 11 landing obscure?

The moon shadow cast by one artist’s timely work points the way. Richard Clar, an environmental artist based in Northern California and Paris who works exclusively in the environment of space, has brought the mission full circle. Two works, one laser-based and one radio-based, were both transmitted from observatories in Europe this July at the exact 50-year anniversary of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon. They rehearse and recall Armstrong’s trepidatious excitement, as well as a legacy of contemporaneous sculpture and Land Art that used lines in space, walking, distance, and the absent human figure. The era was one of extraordinary social change complemented by the growing transformative power of media.

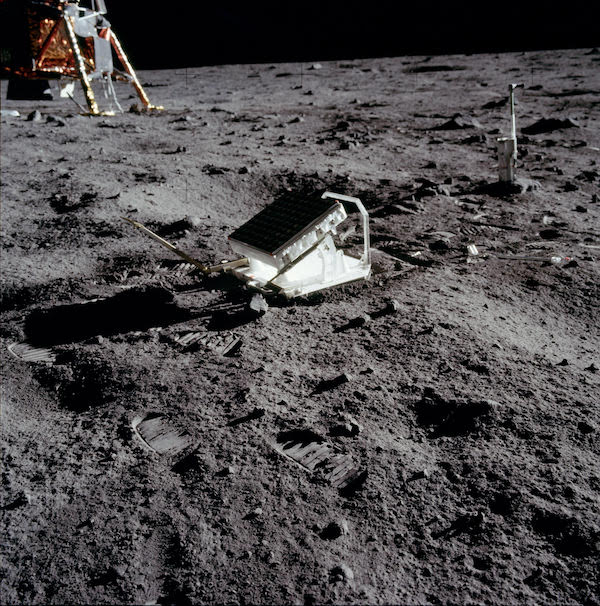

Apollo 11 Retroreflector. Photo credit: NASA.

Clar’s July 21 works are both titled Giant Step. One was a laser transmission sent from the Côte d’Azur Observatory high above the French Riviera at local time 04:56:15 to the exact GPS location where Armstrong’s faded footprint remains undisturbed today. A small retroreflector panel placed there by Armstrong and Aldrin has been used continuously since 1969 for lunar surface laser-ranging, which is used to measure the distance the Moon is receding from the Earth each year, and for substantiating Einstein’s theory of relativity. At the speed of light, Armstrong’s famous statement “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” was beamed back to the same historic spot using Morse code.

Originally developed in the early-19th century, Morse code was the gold standard for maritime distress messages and serves as the link between the lost and troubled seafaring vessel and Clar’s line of light in space. Calling back to Armstrong’s shadow footprint, it reframes the “giant leap” and opens up Armstrong’s quote for reinterpretation. Clar’s is not a leap, it’s just a step, one in a chain. We walk — for pleasure, for protest, toward each other or away. But we have walked in chains, on death marches, and toward the execution chamber too: (Dead Man Walking, dir. Tim Robbins, 1995). Still, Clar reminds us, a few men (no women) have walked on the moon, and those traces of us will remain for eons. In light of everything human, this simple fact seems just cause for celebration.

Telescope projecting laser beam towards the moon at the Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall.

But 50 years is a tiny amount of time in planetary geology, less than an expected error in measurement, such that an observer from another point in time and space might get the sense the landing and the circular utterance had occurred nearly simultaneously. Yet the circularity of reference in the line of transmission creates the roundness and fullness of Clar’s simple but powerfully ephemeral and dematerialized work.

For a moment, let’s consider a few dissimilar contemporaneous visualizations of man’s “Steps”; the first example, the Civil Rights Era Selma to Montgomery protest marches (1965). Second, Richard Long‘s A Line Made By Walking (1967) wherein, trampling the grass in a straight path through an open field with no witnesses, Long referenced prosaic human capacities, and at the same time human frailties and eventual disappearance, recording his traces over the landscape in an iconic black and white photograph now seen as an early progenitor of Land Art. Third: Marvin the Martian and Daffy Duck compete to claim a new planet for Mars or for Earth (Looney Tunes, circa 1969–1970), casually blowing each other up all the while. And fourth: the American Indian Movement (A.I.M.), advocating for rights and sovereignty, leads The Longest Walk, an awareness-raising, spiritual march in 1978 across the country to Washington D.C. (revisited in 2008) to bring attention to anti-Indian legislation.

L to R: Dr. Clément Courde, Alexander Minangoy, Dr. Jean-Marie Torre, Richard Clar, Thierry Hocquaux and Rebecca Marshall, Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO). Calem Observatory, Plateau de Calem, Grasse, France, July 21, 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall.

Clar remembers watching the Moon landing live on TV. He reflects:

Perhaps no other event in human history was seen in real-time by so many people around the world … something I will never forget. At the time, I was not thinking in terms of us, or anyone else, becoming a space-faring nation. My focus was on the present; what was happening right before my eyes. Seeing that first footstep on the moon was somewhat of a mystery. It represented something that was going to happen, but it was not exactly clear what that was.

Yet,

Around one week after the moon landing, I was visiting the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. I struck up a conversation with a group of Native Americans and asked what they thought about our landing on the moon. The unanimous response was that they were not happy at all for they regarded the moon as a sacred space that we somehow violated. So for them, Giant Step has a different meaning.

The history of exploration and conquering, as well as the troubling nature of these Western pastimes, are reflected in the enthusiasm among scientists who wanted to perform and facilitate Clar’s stunt with him. Any artist working in the public sphere needs buy-in, and the message was clearly positive to those on the transmitting end. Difficult to aim a laser at a moon target and hit it at a precise time? Yeah — game on! But what did we accomplish going to the moon? It was a huge leap for industry, and still is a political football that gets thrown around, sometimes by feckless quarterbacks such as our current president, who are trying to leave their own distinctive mark in history: Space Force!

Space artist Richard Clar observes technical preparations for the transmission of his laser message to the moon, part of his artwork Giant Step, at the Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall.

We will soon walk on Mars. Meanwhile, the 50-year-anniversary Moon landing celebrations are unfettered spectacle. They present a particular kind of teaching opportunity, but few take it. That is where Richard Clar‘s second work of July 21, 2019, comes in.

Part dirge, part commemorative memorial, the other part of Giant Step (begun in 2015) uses an EKG of Neil Armstrong‘s heartbeat from NASA’s Apollo archives sonified first into a single tone by Dr. Ryan Compton, then into a heartbeat sound, as the baseline for a remarkable piece of music improvised by LA-based jazz double-bassist Roberto Miranda which is set to video from the moon’s surface of that day. Performed as a “Moonbounce” from the observatory in Dwingeloo, Netherlands — where radio engineer Jan van Muijlwijk and media artist Daniela di Paulis pioneered the technology in 2009 — the moon is used as a huge radio reflector for an Earth-Moon-Earth transmission.

Armstrong’s footprint image after being bounced off the moon. Received by an 25m Astropeiler antenna in Stockert, Germany.

Armstrong’s footprint image after being bounced off the moon. Received by an 25m Astropeiler antenna in Stockert, Germany.

Armstrong’s biometric information, unheard by the public until Clar’s work, provides the insight we need to understand this moment. These are human beings just like us who are being sent out on the most dangerous missions. Like soldiers in war, they are willing to make the greatest sacrifice. While we buy freeze dried ice cream, watch IMAX movies, and proceed in capitalist nostalgic frenzy to the gift shop, we would do well to remember the haptic, the fragile, and the connection to each other. Isamu Noguchi, who also dreamed of doing an artwork on the Moon, has famously said: “If sculpture is the rock, it is also the space between rocks and between the rock and a man, and the communication and contemplation between.”

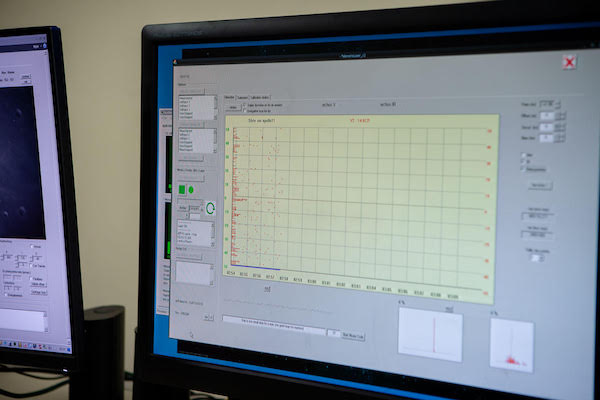

Data screen showing live feed from the laser during the transmission of space artist Richard Clar’s laser message to the moon, part of his artwork Giant Step, Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall.

In our interview, Clar continued to reflect:

I also saw Sputnik 1, launched October 4, 1957. I stood in the backyard of our Hollywood home with my parents as we watched the Russian satellite move across the night sky. It seemed a little ominous at the time, as most people, myself included, had no idea of what it meant. For many in my generation, who grew up during WWII, we were aware that Japan was sending incendiary balloons capable of reaching the US. My parents talked about this and I was afraid. Even as a five-year-old, I was frightened by this idea of balloons starting fires in the US. This created a mindset to be aware of the unknown, or out-of-the-ordinary objects that moved across our skies.

Artist Richard Clar. Photo by Dom Garcia

When Long created his Line, he thought of it as not-art, and an insistence upon being alive. And there was no one watching live on TV. Or Facebook. In a December 2018 article in Wired, Jeff Bezos described his Promethean Blue Origin mission to build space highways inspiring many generations to come: “I hope to create a thousand Mark Zuckerbergs,” he said. If this doesn’t make you pause, as I’m sure it would Armstrong, who was famously mute after his earth-shattering step, well, go back to your social media. In the end, our space-faring dreams are large and speculative, but the reality is certain. Isamu Noguchi brings the absurdity home: “Ultimately, I like to think that when you get to the furthest point of technology, when you get to outer space, what do you find to bring back? Rocks!”